DOWNLOAD

Unless otherwise noted the artwork featured in this article is from the U.S. Army Center for Military History Art Collection. Most of the artists are unknown.

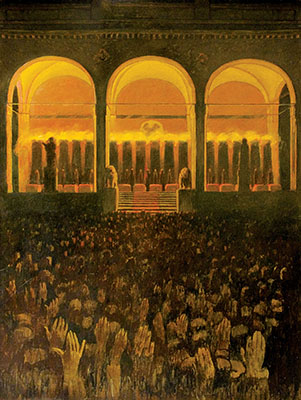

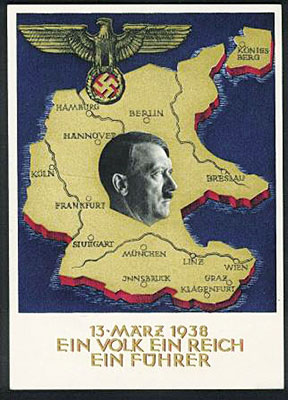

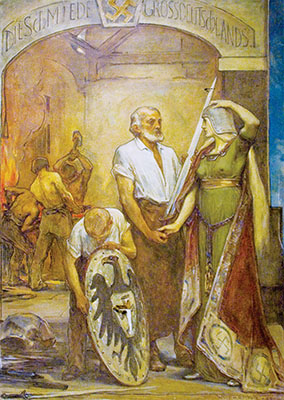

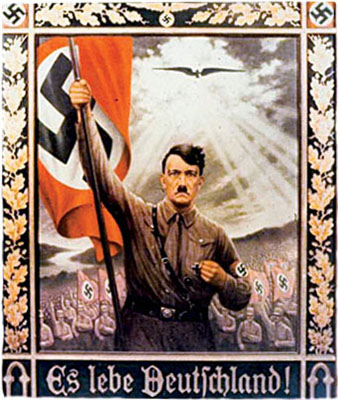

Historically governments have used art as a form of propaganda. Art is usually associated with beauty and inspiration, however totalitarian regimes such as the Nazis, the Soviet Union under Communism, Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and more recently North Korea used art as a propaganda medium. Much of the artwork centering on a “Cult of Personality,” glorifies the leaders of totalitarian regimes and plays an important part in building up a national figure. Perhaps the most intense example is the artwork promulgated by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party. While the topic of Nazi art may seem repugnant, it is a classic study of art used as propaganda. Located in Washington DC is a unique collection of such propaganda, specifically from the Nazis of World War II. This article provides a short historical summary on the rise of Nazi Germany and then shows examples of the regime’s artwork currently in the Art Collection at the U.S. Army Center for Military History.1 “Artwork” covers many mediums, from architecture and design to film, painting, and sculpture; however, paintings are the focus of this article.

Germany’s loss in World War I and the onerous provisions of the Treaty of Versailles provided the breeding ground for widespread discontent. Until October 1918, the Imperial German government controlled all news media. Propaganda extolled the fighting capabilities of the individual soldier and the country’s victories over the western Allies. Suddenly, the government announced an armistice in October 1918, which was in effect a surrender.

Between 1918 and 1923, Weimar Germany was plagued by severe internal crises. From both the left and the right came assassinations, anti-government propaganda, and popular revolts (putsches in German). The already weakened war-damaged economy could not recover; reparations and hyperinflation prevented reconstruction. The period between 1918 and 1923, is described by Professor Claudia Koonz, “The trauma of surrender, economic hardship, and political revolution defined the real world in which most Germans lived. But emotionally they lived in the aftermath of wartime glory … images of brave soldiers and strong women, hymns to a national spirit, and appeals to sacrifice … persisted even as reality left them behind. As Germans experienced hunger, fear of invasion, revolution, and economic disaster, they clung to dreams created by wartime propaganda.”3