ABSTRACT

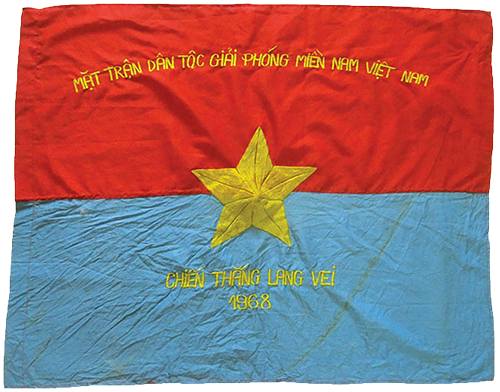

During the Tet Offensive of 1968, a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) tank-led infantry task force overran the northernmost Special Forces (SF) border camp in ninety minutes. It was not a stellar moment for American SF, but Lang Vei blocked direct access to the Khe Sanh Marine base. More importantly, it marked North Vietnam’s shift from supporting a Communist insurgency to conquering democratic South Vietnam by conventional warfare.

SIDEBARS

DOWNLOAD

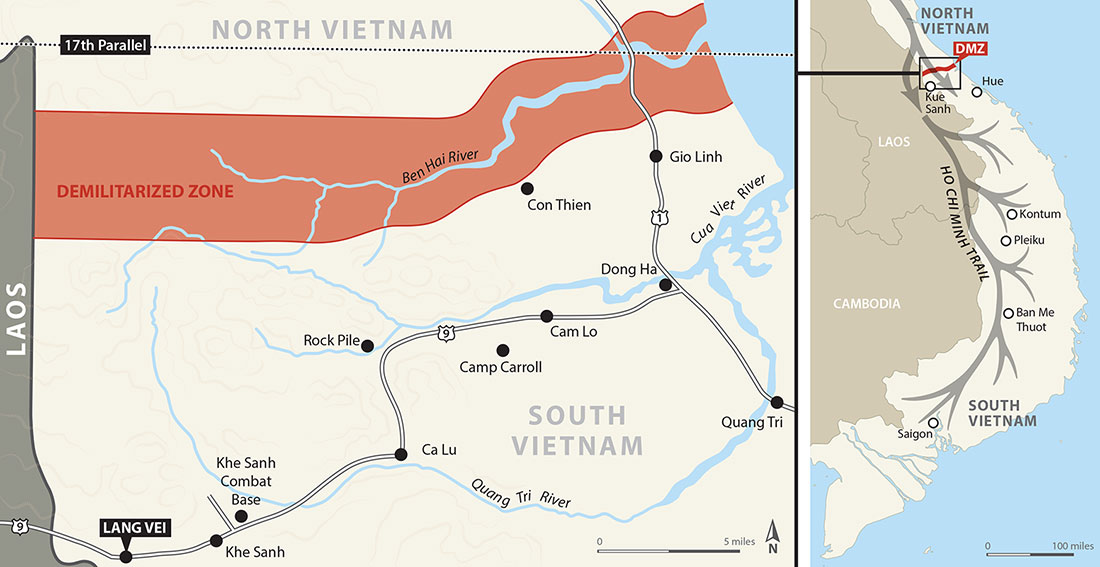

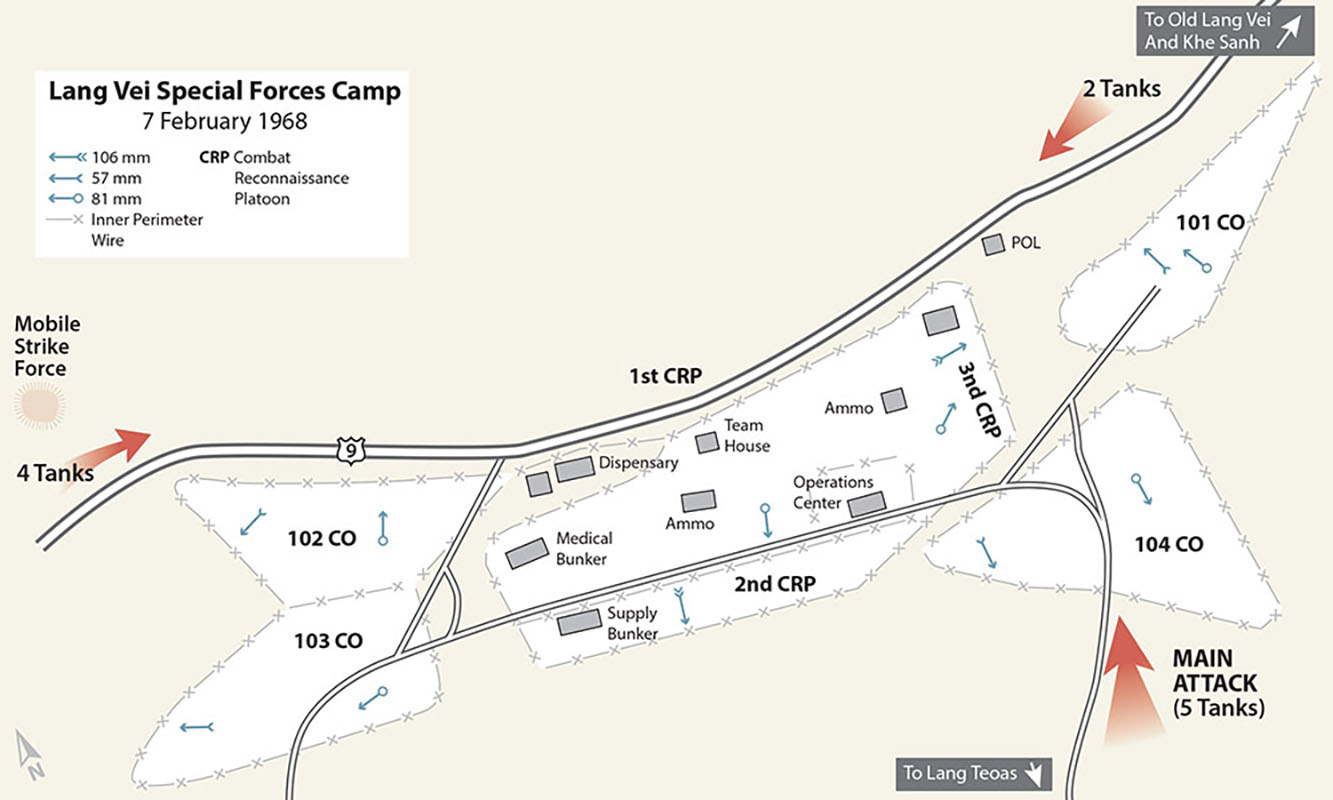

This operational analysis illustrates how a lack of preparedness for an enemy armor attack led to the loss of the Lang Vei SF camp on 7 February 1968. It addresses the first NVA tank employment in South Vietnam, and commemorates veterans of the Vietnam War.1 Early in that war, SF camps were established near highway border crossings into Laos and Cambodia. The principal NVA supply and infiltration route, the north-south Ho Chi Minh trail, was just inside country frontiers. The eastern geographical border of northern Laos, the thigh-deep Se Pone River, was less than two miles from Lang Vei along Highway 9.2

The primary SF border camp mission was surveillance; area pacification was secondary.3 The camps were to become a nuisance to North Vietnamese personnel and supply infiltrations.4 American SF Operational Detachments-Alpha (ODAs) advised the South Vietnamese SF teams ‘supervising’ local Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) soldiers. These volunteers were to defend their camp and actively patrol out to three kilometers to disrupt enemy activity.5 Camps were named after the nearest village where CIDG families lived.6

Seven miles east of Lang Vei was the Bru Montagnard village at Khe Sanh and nearby 26th Marine Regiment combat base. The Marines were ten miles below the demilitarized zone (DMZ) to reduce North Vietnamese access.7 In the spring of 1967, Marine infantry companies fought hard to displace the NVA dug in on mountains overlooking their base. At the same time, Communist South Vietnamese insurgents (Viet Cong [VC]) collapsed eight of the nine vehicle bridges on Highway 9. The attempt to move a 175 mm artillery battery to Khe Sanh to counter the NVA 152 mm artillery in Laos, failed when its convoy was ambushed just six miles outside of Da Nang. The NVA fired 120 mm B-40 rockets from the mountains and one hit their ammo dump destroying ninety percent of the stores. Daily resupply planes landed and took off under enemy artillery fire.8

To further complicate the situation VC destroyed the original Lang Vei SF camp.9 After dark on 3 May 1967, VC sympathizers in the camp helped an attack force to get inside the wire. The two American SF officers, singled out, were killed outright. Most of the SF sergeants were wounded, rendering Detachment A-101 (Det A-101) combat ineffective.10

The 5th SF Group (SFG) quickly reconstituted Det A-101 and had helicoptered it back to Lang Vei before Captain (CPT) Frank C. Willoughby arrived in June. He was directed to rebuild and improve the old camp or find a better location for a new ‘fighting camp.’ The infantry officer saw that the old site was not defensible. A dog bone-shaped hillock overlooking Route 9 between Lang Vei village and the Laotian border was chosen. It could hold four CIDG companies instead of two and its elevation and lack of vegetation supported interlocking final protective fires.11

The construction of fighting bunkers, machinegun positions, mortar pits, and command centers, daily patrolling, camp security, and CIDG recruiting had Det A-101 personnel running ragged.12 CPT Willoughby sought help from the 5th SFG Company C commander, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Daniel F. Schungel. In mid-June 1967, a 36-man Seabee Team with its heavy equipment was helicoptered from Da Nang (Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 11).13 Still, protecting the Seabees while patrolling and maintaining camp security proved difficult.14

1LT Paul R. Longgrear answers the question: How good were these MIKE forces, and why were they good? See the complete interview.

LTC Schungel began to incrementally airlift an SF-led Hré Montagnard company from his Mobile Strike Force (MSF) before Thanksgiving. By mid-December 1967, First Lieutenant (1LT) Paul R. Longgrear, who had been elevated from platoon leader to company commander, had his entire MSF company at Lang Vei. Daily patrols detected enemy presence, strength, and intentions while night ambushes kept the NVA at a distance. Monitoring the Ho Chi Minh trail was another duty. The American SF soldiers daily commanded and led the parachute-qualified MSF ‘strikers’ on combat missions.15 On the other hand, Det A-101 SF personnel advised the South Vietnamese SF who directed Bru CIDG elements on patrols and in camp defense. The ‘aggressive’ Hré Montagnard fighters of the MSF were restricted to an observation post (OP) eight hundred meters away.16 The Navy constructions engineers strengthened U.S. positions.

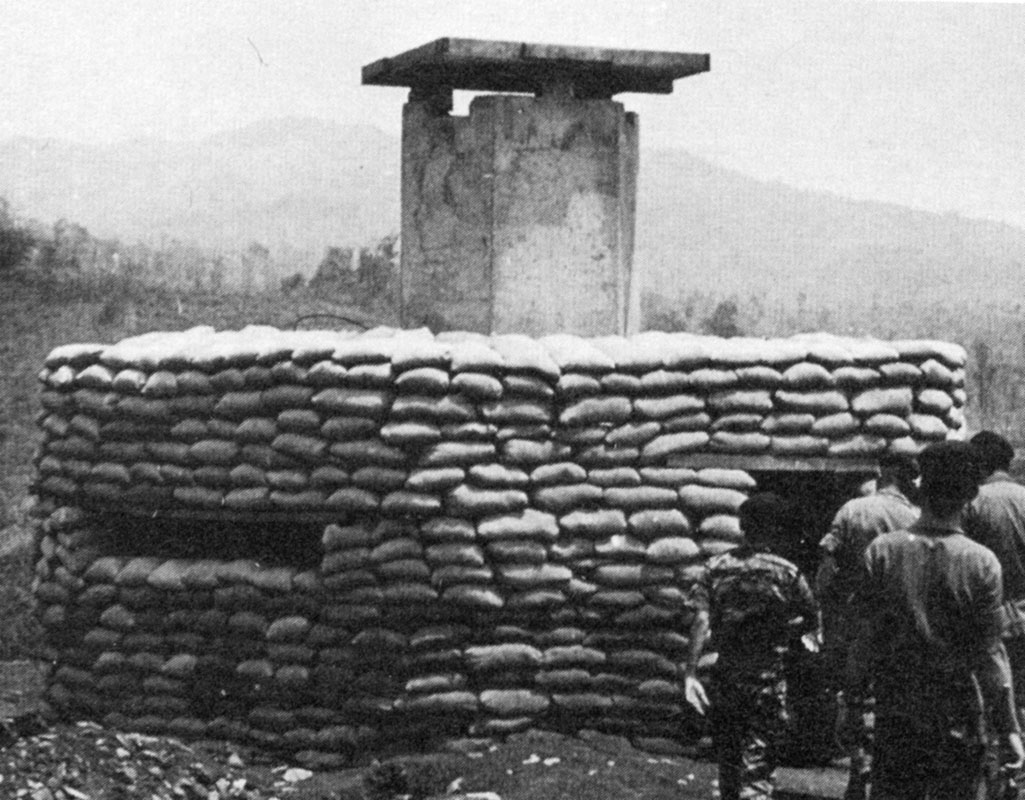

The Navy Seabees ‘hardened’ crew-served weapon pits inside the inner perimeter wire (used by the Americans) with 8 inch thick reinforced concrete walls. They did the same with the operations (ops) bunker. Heavy steel plate entrance, exit, and tower doors controlled access. A prefabricated, reinforced concrete ceiling slab 9 inches thick was topped with 8 by 8 inch wood timbers and laden with sand bags for overhead cover. A 4 foot by 4 foot wide observation tower at one corner of the operations bunker contained an M60 7.62 mm machinegun. The ops bunker was 39 feet by 25 feet and had a 10 foot high ceiling. There were no gun ports because it was not intended as a fighting bunker.17

Just beyond the outer concertina wire NVA reconnaissance teams blatantly watched the construction with binoculars until driven off by small arms fire. The Seabees only improved the inner wire perimeter; CIDG fighting positions along the outer perimeter were sandbagged and had minimal overhead cover. North Vietnamese Antonov An-2 Colt biplanes flew over Lang Vei and occasionally dropped 82 mm mortar rounds to the amusement of the SF soldiers.18 The Navy finished work on 26 November 1967.19 When daily security patrols encountered NVA units, the enemy broke contact, but tank sightings on the Ho Chi Minh trail increased.20

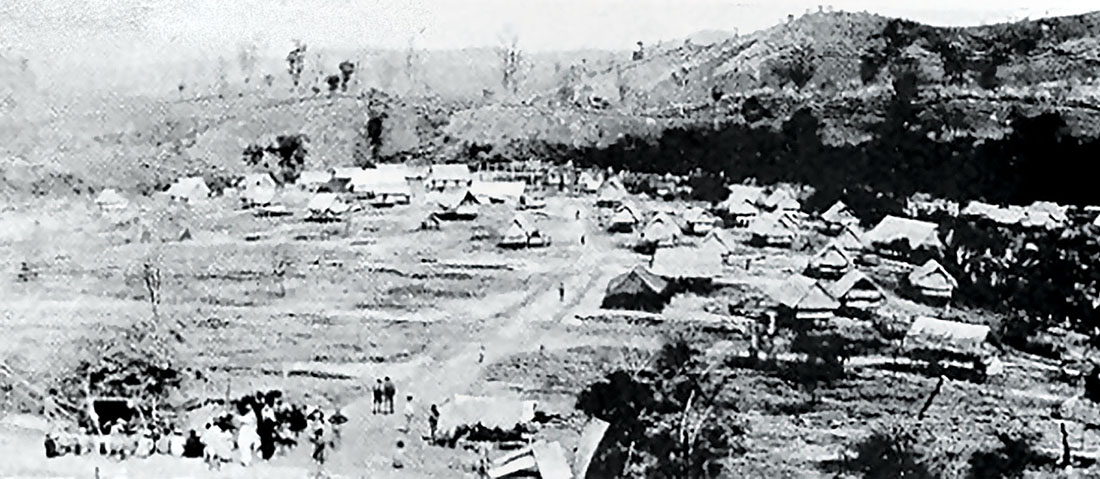

During the night of 21-22 January 1968, an NVA force attacked Khe Sanh village. The 105 mm and 155 mm artillery support from the Marine combat base a mile away prevented the enemy from overrunning a CIDG regional force/province force (RF/PF) security platoon and a U.S. Army advisory team.21 After the 26th Marines declined to send a relief force to reinforce the village defenses or to cover their evacuation, and they rejected an MSF offer to assist, Army CPT Bruce B.G. Clarke, his advisory team, and the RF/PF element walked to the combat base trailed by Bru Montagnard refugees. U.S. personnel were allowed to enter; all indigenous were denied entry.22 Road access to the Lang Vei SF border camp was severed. Two days later, Highway 9 old Lang Vei, and the Bru Montagnard village were inundated with Laotians fleeing the NVA.23

On 24 January 1968, the NVA, reportedly supported by tanks, stampeded the 33rd Royal Laotian Elephant Battalion (520 soldiers) and 2,200 dependents from Tchepone across the border towards Lang Vei.24 Aerial reports of tank sightings and corroborating ground evidence were set aside when Company C, 5th SFG was ordered to support the refugees. An SF major or lieutenant colonel was to liaison daily with the Laotian battalion commander. Three SF medics were flown into old Lang Vei to treat the sick and arrange daily deliveries of food, water, and supplies to the Laotian ‘squatters’ in the remains of the old camp and adjacent Bru Montagnard village.25

The next day Specialist Fourth Class (SP4) John A. Young, a new weapons specialist, was sent from Company C to help Sergeant First Class (SFC) Eugene Ashley, Jr. at old Lang Vei. Twenty-four hours later (26 January 1968), SP4 Young, leading some Laotian volunteers, ignored his ‘orientation patrol’ limits to enter Khe Sanh village. The Laotians fled when they realized that the village was occupied by NVA. They abandoned their American patrol ‘leader.’ Specialist Young was captured and his fate reported to SFC Ashley and MSG Craig.26 Five days later on 31 January, an MSF platoon surprised the NVA security element relaxing in the village. The American leaders reported fifty-four killed and even more wounded. Reinforcements forced the MSF platoon to withdraw, covered by artillery and airstrikes. They returned with more than 30 weapons (‘striker’ reward money). When CPT Willoughby returned from his Hawaii R & R (rest and relaxation), he discounted the tank threat, but strengthened night defenses in the camp with two of the MSF Hré Montagnard platoons despite intertribal tensions27

The Laotian problem in the ‘backyard’ of the fighting camp (old Lang Vei and its Bru Montagnard village were between the new camp and the Marine base) diverted attention from the possibility of an NVA attack during the Tet holiday ceasefire.28 Security in the SF camp hit ‘rock bottom’ on 30 January 1968. An NVA deserter (Private Luong Dinh Du) armed with his AK-47 assault rifle walked through the main gate by the two sleeping Bru guards straight into the SF team house unchallenged. There, he confronted a flabbergasted, weaponless Det A-101 team sergeant preparing breakfast. The deserter told SFC William T. Craig that his battalion executive officer and some sappers had scouted camp defenses two days earlier.29

Despite this blatant security breach and imminent attack warning, the alert condition in the camp was not heightened.30 The country-wide Communist attacks during the Tet holiday ceasefire seemed very distant from the northernmost SF border camp.31 But, the NVA did not ignore them. Daily 152 mm and 122 mm artillery and 120 mm mortar barrages from Co Roc mountain in Laos had become routine. The Americans had assumed a cavalier attitude. They would deal with whatever happened, when it did. But, as Bru desertions grew, their ability to fend off a major attack was reduced.32

During the afternoon of 6 February 1968, LTC Schungel flew in to replace Major (MAJ) Wilbur Hoadley as the SF field grade liaison officer to the Laotian commander.33 His helicopter attracted a fifty-round artillery barrage that wounded several Bru CIDG. Instead of visiting old Lang Vei to liaison, LTC Schungel, once again ‘took charge’ of the SF camp. He grabbed CPT Willoughby and the CIDG sergeant major to check the bunker line before dark. After several perimeter probes drew small arms fire from some Bru positions, quiet came with the heavy fog that settled over the camp. Fifty percent personnel awake was the standard alert posture.34

Just before midnight (6-7 February 1968), NVA sappers, intent on cutting entry paths through the outer concertina wire, tripped illumination flares that alerted the defenders. Two Soviet PT-76 amphibious tanks emerged from the eerie, phosphorescent-lit fog closely followed by two battalions of attacking infantry. They were trailed by more sappers, a heavy machinegun company, and a flamethrower platoon. Two tanks from a second PT-76 company and an NVA infantry company overwhelmed the MSF platoon on the OP while the other six tanks blocked major avenues of approach to the camp.35 It was the first time the NVA had employed tanks in the South.36

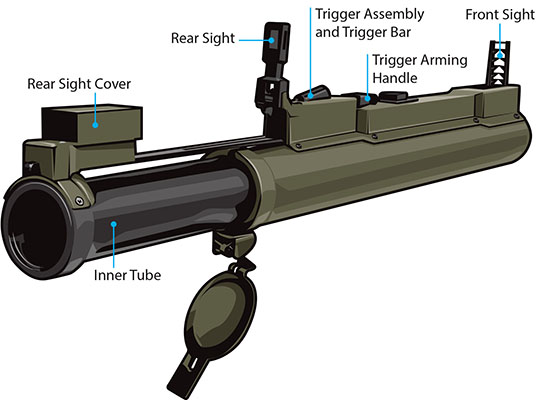

From the inner perimeter SF personnel fired 81 mm and 4.2 inch mortar illumination rounds and engaged the PT-76s with their .50 cal heavy machinegun and one M40 106 mm recoilless rifle (RR). To their front, the four half-strength CIDG companies supported by two MSF platoons activated anti-personnel Claymore mines, engaged with small arms and light machinegun fire, and finally threw hand grenades as the NVA onslaught powered over their defensive positions.37

When the two lead PT-76s, whose tank commanders were ‘spotlighting’ the direction of attack with hand-held searchlights, breached the first line of bunker defenses, the SF-manned 106 RR team ‘killed’ one and disabled the other. Two-man SF tank killer teams, organized and led by LTC Schungel, moved about within the inner perimeter firing M-72 Light Antitank Weapons (LAWs), often point blank. The remaining six tanks proceeded to rumble over the CIDG bunkers from several directions, collapsing them before focusing their firepower on the inner perimeter.38

“It was total chaos…a Wild West fight with Indians everywhere. We were ‘outgunned and vastly outnumbered.’ Everybody outside the ops bunker was doing ‘his own thing.’ Camp defenses were collapsing all around. The NVA tanks and the sapper teams focused first on our ammo and fuel dumps and then the heavy weapon positions to systematically destroy them,” related 1LT Longgrear.39

Eventually, two more PT-76s were stopped. As the remaining four tanks directed their 76 mm guns and machineguns on the LAW teams, the Americans dispersed in the darkness. Contact was lost with the OP. No one knew that the NVA tank-infantry task force which wiped out the OP was part of a second tank company blocking all avenues of approach to the camp, to include old Lang Vei. The SF soldiers in the inner wire crawled under buildings; men outside the front entrance of the concrete ops bunker were ordered inside.40

Despite illumination from AC-47 ‘Spooky’ gunships overhead and intermittent Marine artillery support from Khe Sanh (fired between incoming barrages from Co Roc mountain), the camp defenses were overwhelmed in ninety minutes. As a satchel charge blast ignited the fuel dump, more charges triggered explosions in the ammunition dump. One PT-76 climbed up the earth-tamped wall of the ops bunker hoping to collapse it with 14.6 tons…without success. The radio communications were lost as antennas atop the bunker were smashed. Lights inside went off when the outside generator cable was cut. The personnel inside lost situational awareness of outside activities.41

Sappers tamped multiple explosive shaped charges against ops bunker walls in order to breach the reinforced concrete bolstered by packed earth. Concussion, fragmentation, and tear gas grenades were dropped down air shafts and the observation tower. Shrapnel ricocheting inside the bunker and concrete spalling inflicted wounds. Flamethrowers, aimed at steel doors, elevated temperatures inside, set sand bags afire, and channelized liquid fire, fumes, and smoke down air vents, but the Navy Seabee construction proved impenetrable. Blast pressure from the PT-76 mm main guns hammering steel doors and shape charges ruptured ear drums and blood vessels in eyes and noses, and concussed the trapped defenders.42

Ground relief by the Marines five miles away was deemed too risky at night. The NVA heavy artillery and mortars bracketing the combat camp and airstrip negated preparations for a daytime airmobile assault. Recall that when Khe Sanh village had been attacked on 22 January, the 26th Marines, a mile and a half away, had declined to assist the Army advisors. In reality a Marine rescue/relief of Lang Vei had been nonviable for months.43