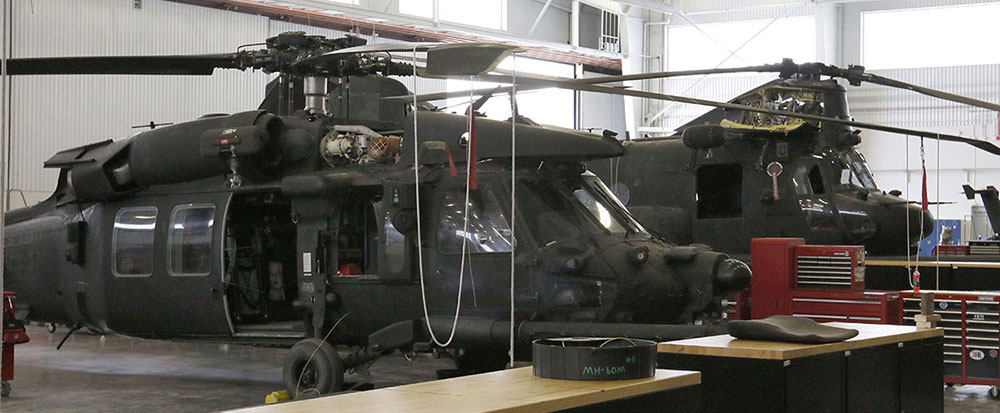

Headquartered in Feistner Hall on Brown Compound, Fort Campbell, the SOATB is commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Bradley D. Osterman. SGM Marcus B. Buker* is the Senior Enlisted Advisor. SOATB “conducts ARSOA individual training and provides education in order to produce crew members and support personnel with basic and advanced qualifications for the [USASOAC enterprise].” By late 2015, SOATB had 359 military, civilian, and contract personnel and its own helicopter fleet (16 A/MH-6s, 9 MH-60s, and 9 MH-47s). SOATB teaches 29 POIs ranging from Combat Skills to Dunker/METS (Modular Egress Training Simulator) Qualification to airframe-specific pilot and Non-rated Crewmember (NRCM) courses. Three SOATB companies develop, support, and teach these POIs: Headquarters Support Company (HSC); Company A (Combat Skills); and Company B (Flight Company).

Activated on 23 July 2015, HSC consists of the battalion command group, staff, and support elements, and three specialty, contractor-dependent sections: the Training Development Support Cell (TDSC), the Allison Aquatics Training Facility (AATF), and the Aviation Maintenance Section. These elements provide critical administrative, maintenance, and training support for SOATB. HSC also administratively supports the Aviation Maintenance Sustainment Office (AMSO) and the Systems Integration Management Office (SIMO). Captain (CPT) Cliff J. Marone* and First Sergeant (1SG) Mark B. Myers*, the command team, are among the 33 active duty HSC personnel. CPT Marone* emphasizes the special hybrid nature of the HSC: “It is unique to have contractors, green-suiters, and GS employees all under the same umbrella, but it works really well.” The TDSC, AATF, and Aviation Maintenance Section thrive because of the contractors. As 1SG Myers* reminded, “Contractors are the continuity within this battalion.”

Run entirely by 30 IDR (International Development and Resources, Inc.) contractors (many retired Night Stalkers), the TDSC functions as the 160th Knowledge Management hub. Located in Chapman Hall on Brown Compound, the TDSC has five functional sections: structural systems developers, publications/technical writers, graphic designers, photographers and videographers, and computer programmers. The TDSC “develop[s], manage[s], and produce[s] training courseware in support of SOA flight and ground training requirements and SOATB POIs. Additionally, TDSC develop[s], publish[es], maintain[s], and distribute[s] USASOAC and 160th-authored publications.” According to the TDSC Project Lead, retired 160th chief warrant officer Daniel E. Fizer*, “We strive to develop products that are technically accurate and instructionally sound with no obvious errors.”

Staffed by nine Survival Systems USA, Inc. contractors, the Allison Aquatics Training Facility has trained approximately 7,000 soldiers in water survival techniques since its opening in March 2009. The AATF follows four TRADOC-approved POIs. First is the two-day Dunker Qualification Course, with A/MH-6, MH-60, and MH-47 helicopter mock-ups used in a manufactured windy, ‘wave-pool’ environment to teach underwater escapes from disabled aircraft. Second is the one-day Dunker Currency Course, required for flight crewmembers every four years. Third is the annually required use of a Helicopter Emergency Egress Device (HEED) (or Emergency Breathing Device [EBD]), a four-hour practical refresher (the HEED requirement is satisfied during initial/refresher dunker training). Lastly, the AATF provides a one-day SOF Ground Forces Water/Survival Egress Course for 160th ‘customers’ to prepare them as passengers for a downed aircraft situation. According to the Facility Manager, retired 5th SFG diver Christian D. Schmidt*, “We get a lot of positive feedback. Soldiers and aviators who have gone through dunker training at other facilities say that our training here far exceeds the others.”

The final, HSC contractor-dependent element is the Aviation Maintenance Section. The Production Control Officer, retired CSM Mike C. Gallico*, has an NCOIC to help him manage the 130 Lockheed-Martin general maintenance contractors, many of whom are former Night Stalkers. This group does scheduled (or ‘phased’) maintenance (MH-47s and A/MH-6s every 300 flight hours and MH-60s every 360 hours) and regular maintenance on the SOATB helicopters used by Company B. According to Gallico*, “There’s a lot of effort that goes into this. Kudos go to the guys with the wrenches working in the cold, rainy weather to keep these aircraft flying.”

As the SOATB proponent for Combat Skills, Company A is truly the ‘first step’ for officers, warrant officers, and soldiers entering the 160th SOAR. It “reinforce[s] Army SOF attributes and prepare[s] soldiers for varying combat environments … The student and his or her corresponding team are purposefully placed under stress throughout the course utilizing scenario-based training.” The Officer and Enlisted Combat Skills POIs have four distinct areas of instruction: First Responders (medical), Land Navigation, Modern Army Combatives, and Advanced Combat Shooting, with basic soldiering skills reinforced throughout. SOATB Combat Skills POIs are explained in subsequent articles on Officer and Enlisted ‘Green Platoon’ training.