ABSTRACT

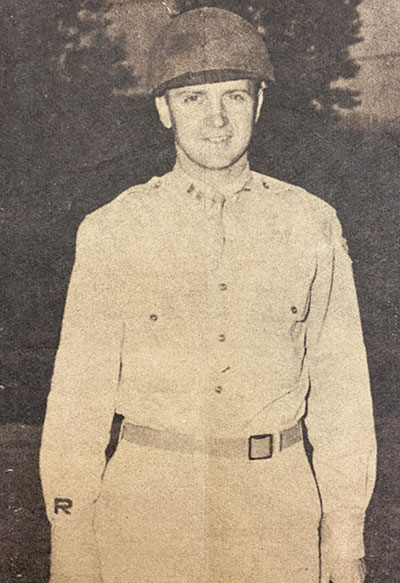

This article, centered around a ‘Commando’ instructor at the Amphibious Training Center who created the 4th Division Ranger program, explains why individual troop-building skills were critical to preparing a draft Army for war. Both programs developed Army junior leaders ‘on the cheap’ by providing practical methods to ‘steel’ recruits for combat overseas. Intertwining the professional growth of Captain Oscar L. Joyner, Jr., 8th Infantry Regiment, with the environment of 1940s America reveals the state of U.S. military preparedness while war was raging throughout the world.

SECTIONS

TAKEAWAYS

- WWII Ranger programs, built on British Commando training methodology and combat-proven skills, challenged, motivated, and produced junior officer and NCOs capable of molding draftees into fit, confident soldiers, capable of winning in combat.

- The two years of ‘Commando,’ Ranger, and amphibious training organized and run by CPT Oscar L. Joyner, Jr. saved countless lives in the 36th and 4th ID and other divisions while making leaders of several hundred corporals, sergeants, and junior officers.

- Physical training can be done anywhere, anytime; demonstrate how to overcome tough obstacles and then make ‘enabled’ soldiers face those challenges every day and at night.

DOWNLOAD

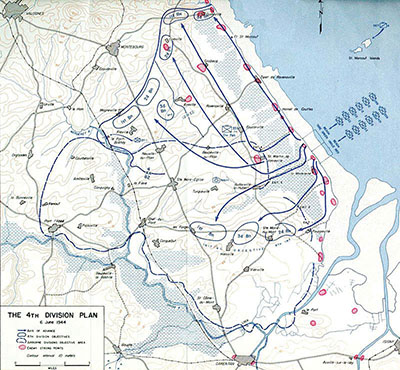

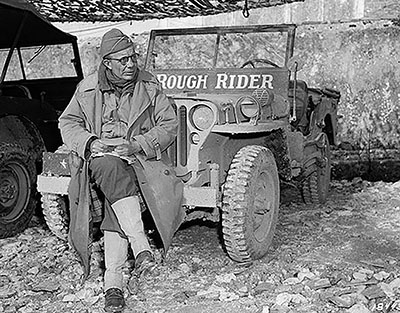

This article emphasizes how important ‘Commando,’ Ranger, and amphibious training were in preparing America’s soldiers to fight on multiple fronts in World War II. Infantry Captain (CPT) Oscar L. Joyner, Jr., 4th Division, was prepared to organize a ‘shoestring’ Ranger program after six weeks of Commando training at Camp William, Achnacarry, Scotland, in 1942.1 This was proven when he was diverted for ‘Commando’ instructor duty at the new Amphibious Training Center (ATC) at Camp Clarence R. Edwards, Massachusetts. When CPT Joyner rejoined the 4th Division in November 1942, he brought a wealth of field expedient individual and collective ‘Commando’ training and amphibious operations experience.2 By chronicling CPT Joyner’s professional development during the feeble Army modernization during America’s mobilization for World War II will show his ‘value-added’ to 4th Division.

Sidebars will connect Joyner’s military progression with the state of Army junior officers in 1940; the credentials of his mentor, one of the Army’s strongest leaders, commanders, and trainers at the battalion and regimental level; and the spread of war worldwide. The U.S. Army ranking among nations, second and third order effects of British, Chinese, and Russian combat losses, pacifist impacts on conscription, and defense priorities before Pearl Harbor serve as the atmospheric context. They help one better appreciate the importance of ‘shoestring’ training for a draftee Army. All of these factors increased the pressure on junior officers and sergeants charged with daily transforming new recruits into combat-capable soldiers. Severely resource-constrained British Commando improvised training methodology and combat skills became the templates for Ranger programs. Combat marksmanship and urban fighting were emphasized as well. Consider these factors along with life in small town America in the early 1940s.