ABSTRACT

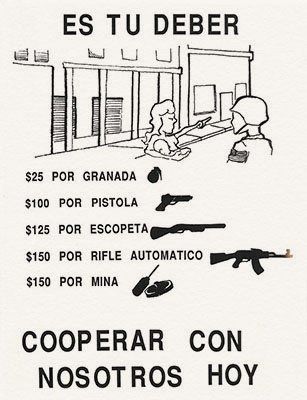

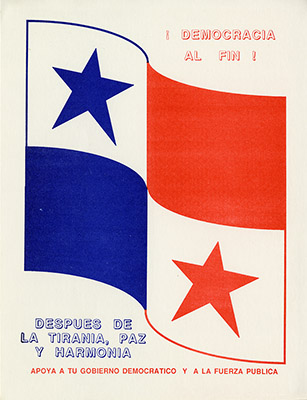

When Operation JUST CAUSE in Panama began on 20 December 1989, loudspeaker teams from the 4th Psychological Operations (PSYOP) Group accompanied invasion forces. Days later, they were reinforced by a PSYOP Task Force (POTF), which expanded the PSYOP effort. Together, PSYOP soldiers helped reduce casualties; garnered Panamanian support for U.S. forces and the new government; and promoted the successful ‘guns for money’ program.

TAKEAWAYS

- Early integration of PSYOP into contingency planning proved critical to its effectiveness in Operation JUST CAUSE

- Although the POTF main body did not arrive until D+4, PSYOP forces were adequately manned, equipped, and employed throughout JUST CAUSE

- PSYOP in JUST CAUSE provided an invaluable ‘dress rehearsal’ for Operations DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM, particularly for 4th POG leadership and 8th POB soldiers

DOWNLOAD

On CBS Evening News on 1 January 1990, anchorman Dan Rather displayed aerial imagery of the Papal Nunciature in Panama City, Panama, the hideout of dictator Manuel Noriega. After showing U.S. military roadblocks, Rather pointed to another spot, saying, “Over here … is a speaker system through which statements by President [George H.W.] Bush and rock music are being pumped out on a 24-hour-a-day basis as part of a psychological pressure that the U.S. wants to keep drumming into Noriega inside that compound.”1 This “pressure” being applied by soldiers from the 1st Psychological Operations (PSYOP) Battalion, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was part of a broader PSYOP effort during Operation JUST CAUSE.

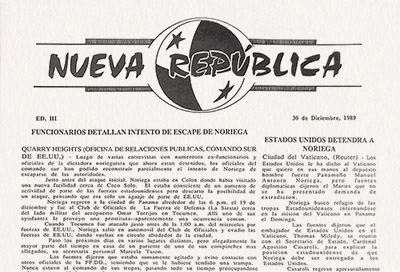

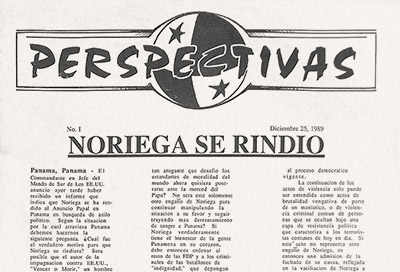

This article details PSYOP in Panama from 20 December 1989 through mid-January 1990. First, it explains pre-conflict PSYOP preparations, including the development of print, audio, and visual products, and plans for a PSYOP Task Force (POTF). Second, it summarizes the role of tactical loudspeaker teams in combat operations on and after D-Day. Third, it describes the arrival of 4th PSYOP Group (POG) (-) and the POTF on D+4, and the ensuing multifaceted PSYOP effort through January 1990. Finally, it summarizes PSYOP output, impact, and lessons learned, and concludes that it made key contributions to the U.S. mission in Panama.

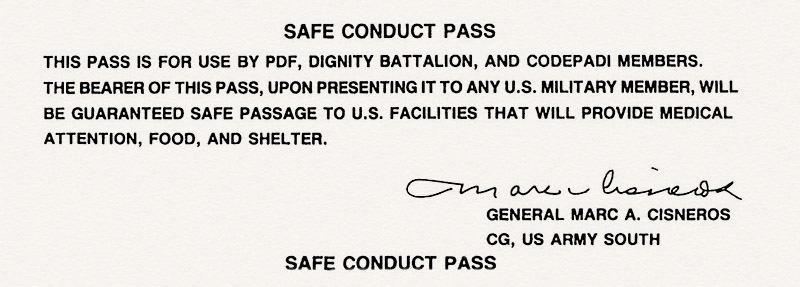

PSYOP planning began long before JUST CAUSE, the mission to remove Noriega, the Panama Defense Forces (PDF), and Dignity Battalion (DIGBAT) paramilitary squads, and help restore a democratic government. The commander of the U.S. Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM)-aligned 1st PSYOP Battalion (POB), Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Dennis P. Walko, knew key players on the USSOUTHCOM and U.S. Army South (USARSO) staffs. He had also previously worked for Lieutenant General (LTG) Carl W. Stiner, Commanding General, XVIII Airborne Corps and, later, Joint Task Force (JTF) - South, during JUST CAUSE. The 4th POG commander, Colonel (COL) Anthony H. Normand, also had a positive relationship with XVIII Airborne Corps. Walko stated in hindsight that “liaison between us and USSOUTHCOM [and] XVIII Airborne Corps was extremely easy.”2 PSYOP was thus ‘plugged into’ Panama contingency planning early on, correcting a noted failure from Operation URGENT FURY in Grenada in 1983.3