ABSTRACT

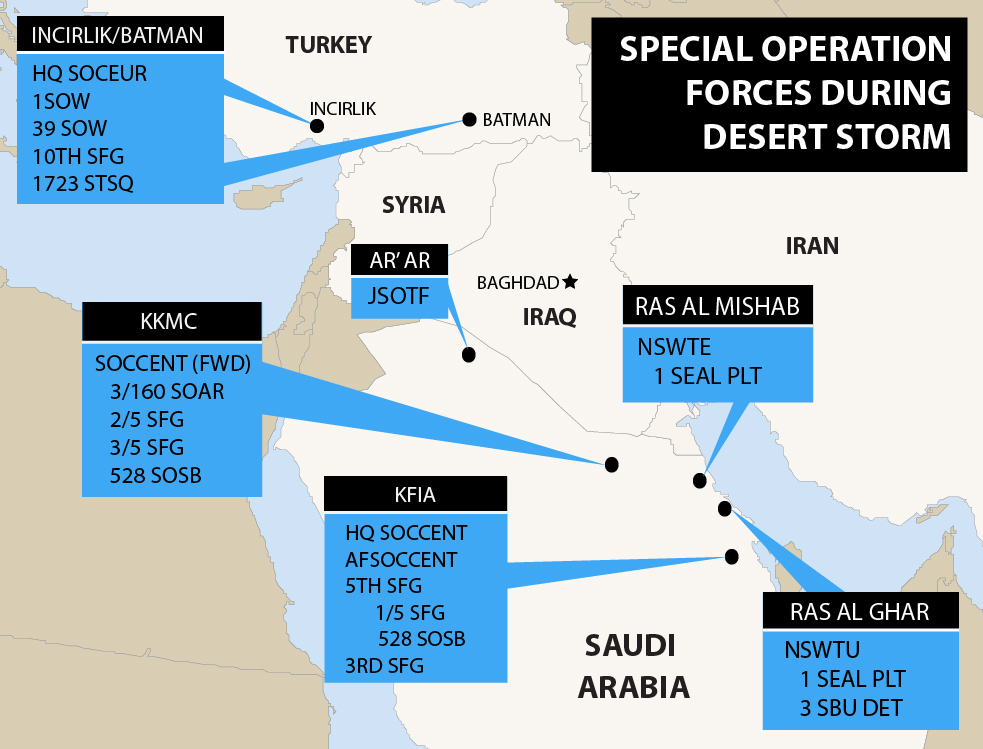

Temporarily spared inactivation following Operation JUST CAUSE, the 528th Special Operations Support Battalion’s fate remained undecided when Iraq invaded Kuwait on 2 August 1990. Consequently, its involvement in U.S. military operations to defend Saudi Arabia (DESERT SHIELD) and liberate Kuwait (DESERT STORM) was not a foregone conclusion. But, when U.S. Special Operations Command, Central (SOCCENT) needed an immediate logistics solution for Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) deploying to Saudi Arabia, it requested the 528th. This proved to be a fortuitous decision for both the 528th and the myriad ARSOF units they supported.

TAKEAWAYS

- Though unplanned, 528th SOSB support to the ARSOTF and SOCCENT was critical to mission success during DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM

- The 528th was stretched extremely thin for the duration of the conflict, operating out of multiple locations, supporting a wide array of SOF and conventional forces

- 528th SOSB contributions to Operation JUST CAUSE in Panama led the Army to postpone its activation, but its excellent performance in Operation DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM secured its existence for another fifteen years

DOWNLOAD

Operation DESERT STORM concluded on 28 February 1991, after six weeks of intense aerial bombardment and a 100-hour ground campaign that ejected Iraqi forces from occupied Kuwait. Commenting on the rapid and overwhelming success of that operation, General (GEN) H. Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr., Commander-in-Chief (CINC), U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM), singled out U.S. Special Operations Forces (SOF) for praise, referring to them as the glue that held the diverse U.S.-led coalition together.1 Schwarzkopf did not specifically mention the 528th Special Operations Support Battalion (SOSB), but his senior SOF commander in theater, U.S. Army Special Forces Colonel (COL) Jesse L. Johnson, described the 528th as his “saving grace.”2 Johnson’s deputy, U.S. Air Force (USAF) Colonel Douglas Brazil, echoed that sentiment: “we’d have died without them.”3 Viewed in this light, the 528th SOSB was a critical, but largely overlooked, ingredient in Schwarzkopf’s “glue.”

Few published histories of the Persian Gulf War, as Operations DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM are commonly known, address the 528th SOSB’s role.4 However, several unpublished histories, including those produced by the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) History Office, devote a few paragraphs to ARSOF combat service support (CSS) in this conflict.5 These accounts typically describe 528th SOSB contributions in terms of quantities: number of miles travelled, requisitions filled, maintenance jobs completed, and meals distributed. They do not provide context for understanding these numbers, nor do they put faces on the ARSOF Support soldiers responsible for sustaining ARSOF.6 In contrast, this article fills that gap by relating how this small, one-of-a-kind support battalion, with limited operational experience and no role in existing USCENTCOM plans, deployed to Saudi Arabia and helped sustain ARSOF during the U.S. military’s largest ground campaign since the Vietnam War.

Background

In 1986, the U.S. Army activated the 13th Support Battalion (Special Operations) at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to provide dedicated logistical support to ARSOF units assigned to 1st Special Operations Command (1st SOCOM). Commanded by Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Louis G. Mason, its 163 soldiers were organized into a headquarters company (HHC) and three functional detachments (Supply, Maintenance, and Transportation). In May 1987, the Army reflagged the 13th as the 528th Support Battalion, better known as the 528th SOSB. Soon thereafter, it began deploying small contingents to Bahrain to support ARSOF in Operations EARNEST WILL and PRIME CHANCE - the so-called “Tanker War” with Iran that lasted from 1987-1989.7 That mission was ongoing in May 1989, when the Army ordered the 528th’s inactivation, effective September 1990.8

528th Special Operations Support Battalion

RELATED: Almost a Footnote: The Special Operations Support Battalion, 1986-1989

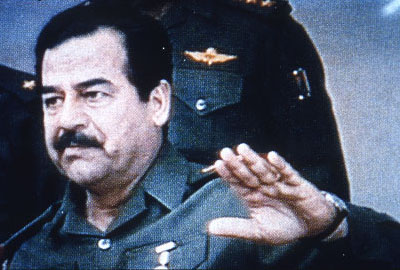

Rather than passively wait for inactivation, 528th leaders successfully inserted it into U.S. Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) contingency plans for Panama. In December 1989, two task-organized elements from the 528th, totaling thirty-seven soldiers, deployed in support of Operation JUST CAUSE.9 The 528th’s performance there convinced the CINC, U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), GEN James J. Lindsay, to ask the Army to reconsider its inactivation decision. At a March 1990 meeting with Lindsay, GEN Robert W. Riscassi, Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, agreed to postpone the inactivation, pending a comprehensive study of ARSOF CSS.10 This study was underway when Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s tanks overran neighboring Kuwait that August.

The 528th SOSB gained valuable experience in Panama but, like many USASOC units, had not yet been tested by an extended, large-scale deployment. It would now get that opportunity, due in part to deficiencies in the USCENTCOM plan for supporting ARSOF during contingency operations. Between August 1990 and March 1991, 155 soldiers – 96 percent of the 528th’s total strength – deployed to the USCENTCOM area of operational responsibility (AOR). Their actions there ensured the battalion’s survival.

RELATED: “Proving the Concept”: The 528th Support Battalion in Panama

Planning and Deployment

Inclusion in USSOUTHCOM plans, prior to JUST CAUSE, allowed the 528th SOSB to stage equipment and rehearse with supported ARSOF elements.11 Nothing of this nature existed for USCENTCOM.12 As a result, the 528th’s role in DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM was largely an exercise in improvisation.

Existing plans and doctrine gave SOCCENT, the theater special operations command for USCENTCOM, operational control (OPCON) of all ARSOF in theater. However, it was not responsible for their logistical support. That responsibility fell to U.S. Army Central Command (ARCENT), the Army Service Component Command (ASCC) for USCENTCOM.13 ARCENT’s plans called for a mobilized U.S. Army Reserve (USAR) Army Support Group (ASG) to support ARSOF during contingency operations.14 However, the planned ASG could not arrive in theater for at least seven weeks after the SOF units it was to support, a problem identified by SOCCENT at a March 1990 planning conference.15 Finally, the SOF element intended to coordinate ARSOF logistics in the USCENTOM AOR, 5th Special Operations Support Command (SOSC), would not activate until October 1990, which was too late to have any impact on DESERT SHIELD.16

On 7 August 1990, U.S. President George H.W. Bush ordered the deployment of U.S. forces to Saudi Arabia, to deter further Iraqi aggression. COL Jesse Johnson and his staff immediately began making preparations for a SOCCENT-Forward headquarters (HQ) on the Arabian Peninsula.17 Knowing the weaknesses in the ARCENT support plan, he asked Lieutenant General (LTG) Michael F. Spigelmire, Commanding General, USASOC, for the 528th SOSB, being familiar with its recent contributions during JUST CAUSE.18 1st SOCOM, the 528th’s higher headquarters, recommended deployment two days later.19

LTC Norman A. Gebhard, 528th SOSB Commander, alerted his battalion, which immediately began preparing to deploy to Saudi Arabia. One junior officer recalled the soldiers being too consumed by the task at hand to worry about what lay ahead. Instead, the prevailing sentiment among the troops was that Iraq, which fielded the fourth largest army in the world at the time, “didn’t know what it was getting into.”20

When LTC Gebhard assumed command of the 528th in July 1990, it was his second consecutive SOF assignment on Fort Bragg. However, he had spent the first fifteen years of his career in the conventional Army, experience that would serve him well during the upcoming deployment. He was aided by battalion Command Sergeant Major (CSM) Otis W. Norfleet, a JUST CAUSE veteran who had been the battalion CSM since mid-1988. Joining him were fellow Panama veterans Major (MAJ) Randy R. Heyward (Executive Officer), Captain (CPT) Robert T. Davis (S-3, Operations Officer), CPT Mark A. Olinger (Support Operations Officer), CPT John M. Gargaro (Commander, HHC), and Sergeant First Class (SFC) James E. Boone (S-4, Noncommissioned Officer-in-Charge [NCOIC]).21 Their combined experience made it possible to deploy the entire battalion into a largely unknown environment in less than a month, and then hit the ground running.