DOWNLOAD

The U.S. created a number of Special Operations units during World War II. While a few of them, such as the First Special Service Force, Merrill’s Marauders, and elements of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) are well-known, others have slipped into anonymity. Even within the OSS, there are some units and projects that remain largely unknown. One OSS veteran, former Sergeant (SGT) Frank J. Skokoski, served in three obscure Special Operations elements in WWII. These units, BARDSEA, Operational Group ADRIAN, and the Special Allied Airborne Reconnaissance Force (SAARF), exemplified the inter-allied cooperation needed to rid Europe of Nazi domination. This article illustrates three main points. First, it provides snapshots of the unique units in which Skokoski served. Second, it describes some of the peripheral missions that Special Operations units assumed during WWII, even if they were never fully executed. Third, it emphasizes how, despite the best planning and preparation, the rapid development of events can render some Special Operations missions unnecessary.

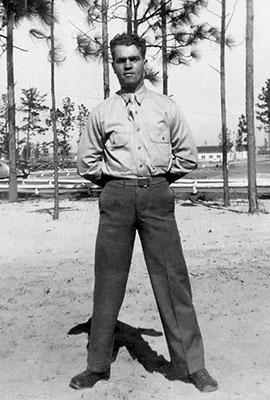

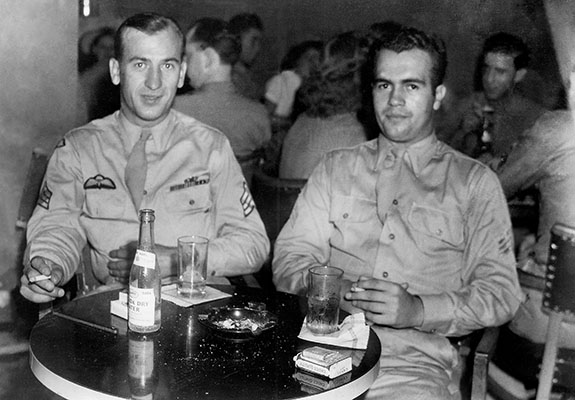

Skokoski followed an indirect route into Special Operations. Born in 1924 in Hazelton, Pennsylvania, to Polish immigrants, Skokoski grew up speaking his parents’ native language at home and English outside. A week after finishing high school in 1942, he enlisted in the U.S. Army.1 His first assignment was as a medic in the 79th Infantry Division, but Skokoski did not find that duty very exciting. He volunteered for the paratroopers, admitting later that he did “not even know about the extra pay.”2 In August 1943, after completing the Basic Airborne Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, Private Skokoski received an assignment to the 541st Parachute Infantry Regiment at Camp Mackall, North Carolina. In December 1943, he participated in the Knollwood Maneuvers in North Carolina that tested the viability of a division-sized airborne force.3 Then, early in 1944, he left the 541st and deployed by ship to Northern Ireland as an airborne replacement.

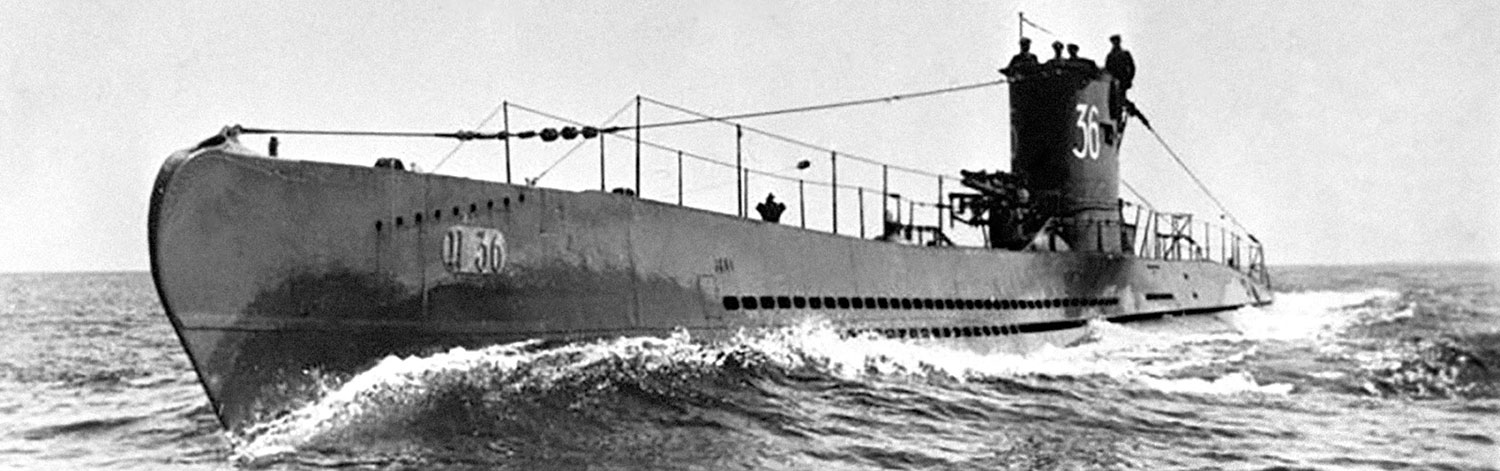

The twenty-day voyage was not pleasant because German U-Boats still roamed the Atlantic and had sunk hundreds of Allied ships during the previous two years. As a counter-measure to torpedoes, Skokoski’s ship zigzagged the entire way to Ireland. That resulted in a longer voyage through choppy North Atlantic seas that made many passengers seasick. The unappetizing fare on board compounded their misery. “They gave us horsemeat” to eat, remembered Skokoski.4

After safely arriving in Ireland and being sent to a replacement depot, Skokoski was surprised when he was approached by OSS recruiters who asked “Do you speak Polish?” Answering “yes,” the recruiter then asked “How would you like to jump behind the lines?” After again answering in the affirmative, the OSS then tested Skokoski’s language ability. “They took us to London where a whole bunch of [uniformed] English and Polish officers questioned you.”5 The volunteers were told to converse completely in Polish. Those who passed the language test were accepted into the OSS Special Operations (SO) Branch, the element charged with conducting sabotage and providing liaison to resistance movements.6

The OSS needed Polish speakers because of a complicated geopolitical situation that had arisen in Europe after decades of German aggression. Although it emerged victorious from World War I, France lost a significant percentage of its working age male population to combat losses. Postwar France turned to immigration to keep its coal mining industry functioning. Seeking a better opportunity, thousands of Poles immigrated to work in the mines in northern France.

But, the post-World War I peace did not last. On 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany and its allies, the Soviet Union and the Slovak Republic, invaded Poland. The country fell in a month, but a Polish Government-in-Exile managed to flee to London, England. Then, on 10 May 1940, Germany attacked France. In six weeks, most of France was under German occupation.7

Thereafter, the Allies tried to regain contact with the continent so that they could foster intelligence networks and resistance elements. In late 1942, the Polish Government-in-Exile established clandestine contact with the Polish community living in north France. The nearly 200,000 Polish expatriates represented a potential source of friendly manpower that the Allies could not ignore.8

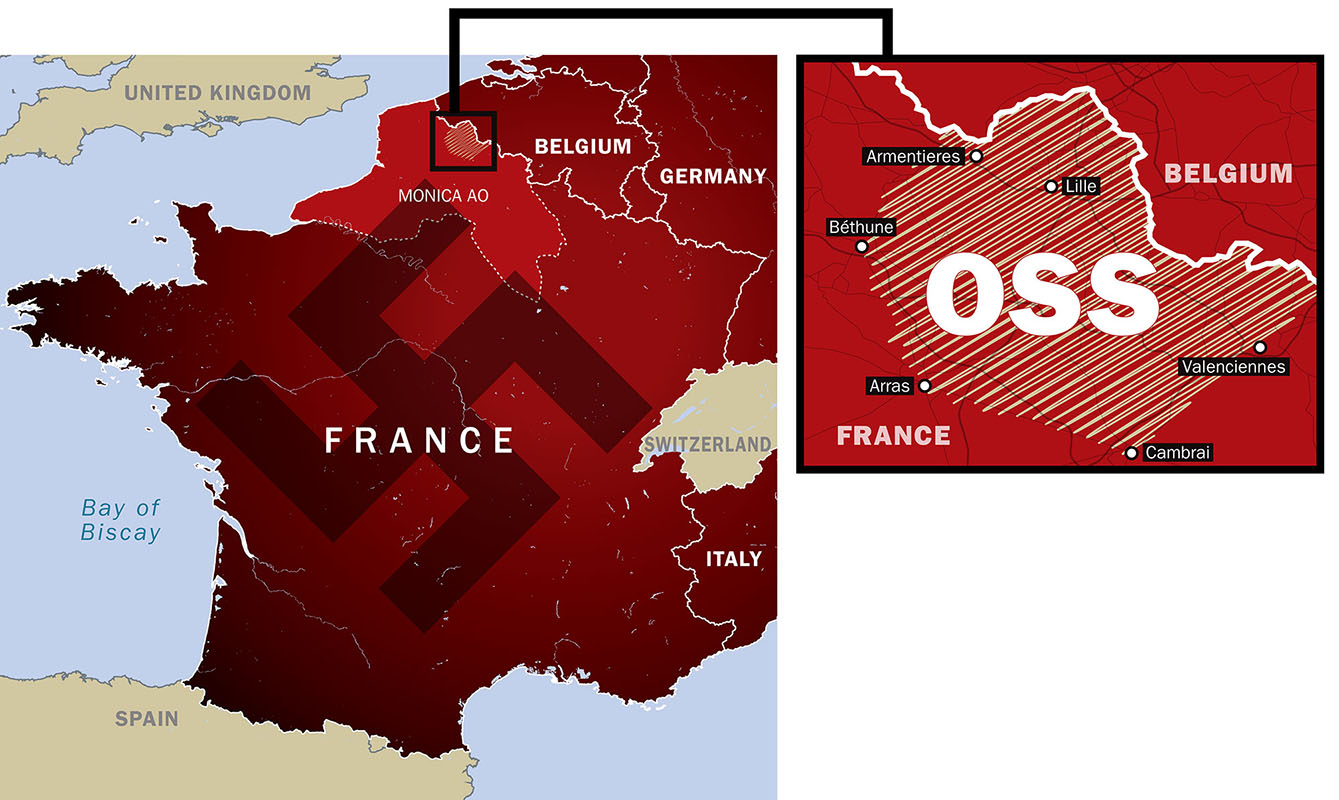

The British equivalent of the OSS, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) assumed the task of exploiting this human resource.9 SOE reasoned that it could organize the Poles in France into resistance cells. Code-named MONICA, SOE’s plan called for recruiting 2,500 Polish cell leaders. The cell leaders would then each recruit “5 men sworn to take part in any task given to them.” In theory, MONICA would result in a resistance movement of about 15,000 members centered on the towns of Armentieres, Bethune, Arras, Cambrai, Blanc, and Misseron.10 The Polish Government-in-Exile had overall authority for the project and conceptually hoped to have a division-sized resistance element in Northern France. This would augment the nearly 195,000 men that had escaped from German-occupied Poland and who were then fighting under British command.11

In 1942, SOE and the Polish Government-in-Exile established the BARDSEA Project to help accomplish MONICA.12 BARDSEA consisted of thirty teams (five or six men each) that were to function much like the more well-known Jedburgh Teams.13 The BARDSEA teams would help train and arm the activated Polish resistance in France, ambush targets of opportunity, and serve as a communications link between the local MONICA cells and SOE.14

However, the Polish Government-in-Exile, given overall authority as to when to implement BARDSEA, proved reluctant to insert the teams. The London Poles correctly reasoned that if the French Poles began conducting overt resistance acts too early, they would become easy targets for German reprisals. Therefore, the Polish Government-in-Exile decided that it would only commit the BARDSEA units when conventional Allied forces could reach the teams in less than 72 hours.15

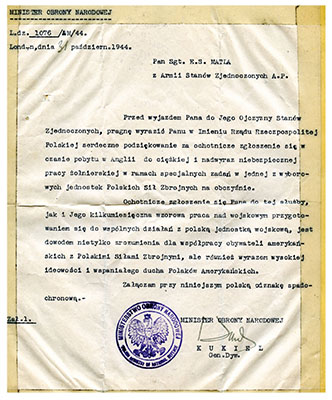

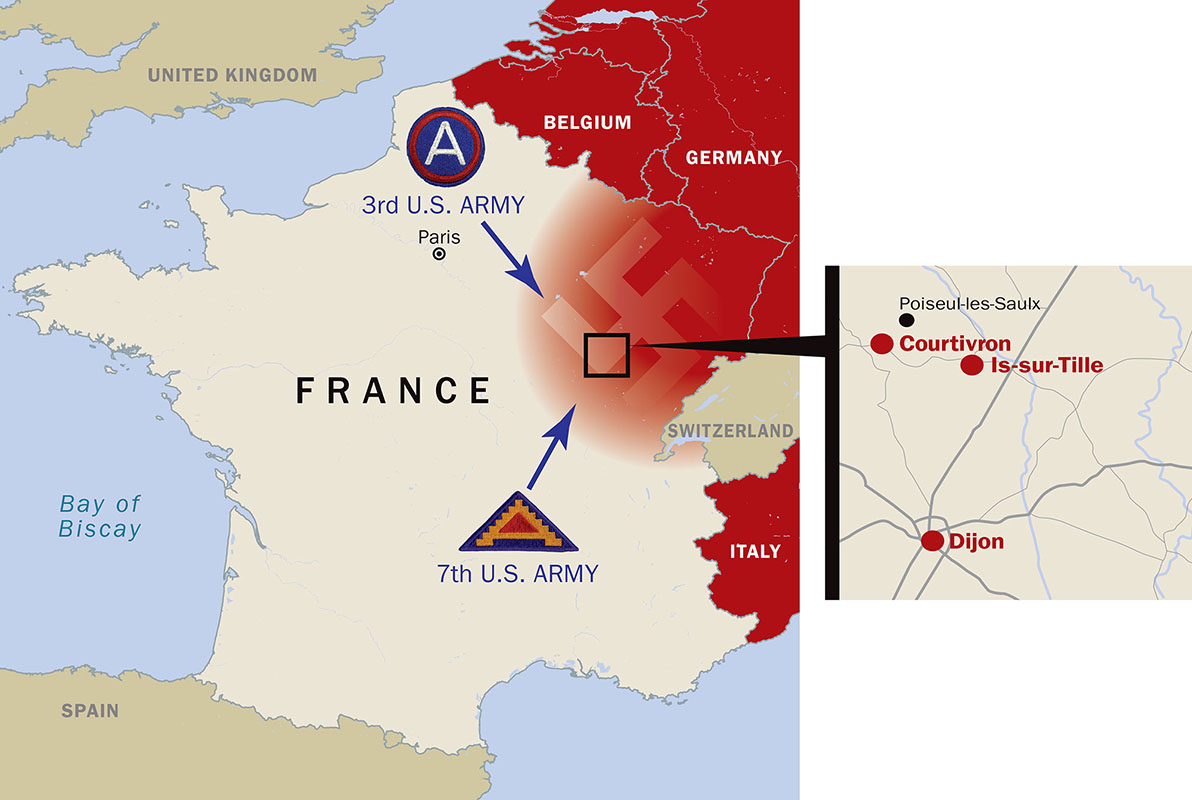

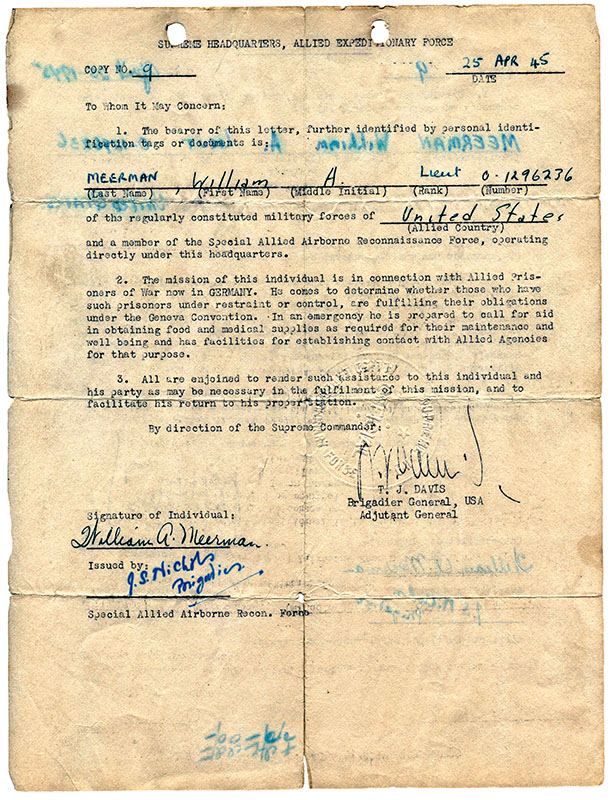

The OSS became involved in the project in early 1944 when the command and control of OSS SO and SOE operations in northwest Europe were integrated under the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). The OSS SO Branch provided fourteen personnel to BARDSEA.16 Supplemented with one Polish radio operator, the OSS BARDSEA contingent was divided into three five-man elements, designated as the DODFORD, DUNCHURCH, and DACHET Groups. Skokoski was assigned to DACHET.17