NOTE

To avoid confusion and provide clarity, field recovery team (FRT) will be used throughout.

DOWNLOAD

The purpose of this introductory article is to show that the modus operandi for resolving American missing in action (MIA) cases was viable in South Vietnam from 1972-1974, despite U.S. combat troop withdrawals. It demonstrates that the information campaign prepared by psychological operations (PSYOP) was as critical to ‘prepping the area of operations (AO)’ as it is today. PSYOP designed information solicitation products for audiences ranging from illiterate village elders to grade school children in rural areas worked just as they do today in Afghanistan and Iraq. Targeting basics remain timeless. The article is centered around the experiences of a Vietnam PSYOP veteran, Major (MAJ) Paul D. Mather, who served fifteen years in the Joint Casualty Resolution Center (JCRC).

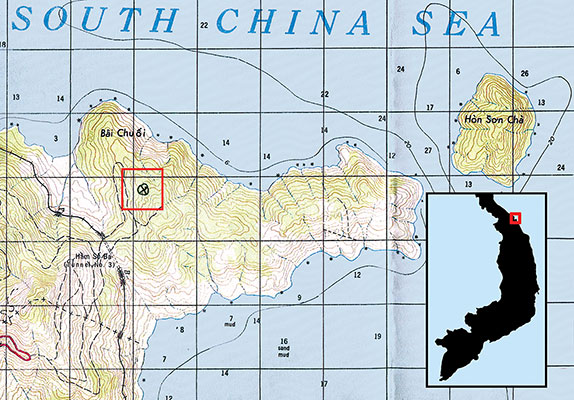

As the U.S.-driven Paris Peace negotiations proceeded, JCRC was created by the U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM) to resolve the status of some 2,500 MIA and MIA/BNR (body not recovered) military and civilians unaccounted for during hostilities throughout Southeast Asia (SEA). By conducting humanitarian operations it was to find and investigate more than 1,000 reported aircraft crash and grave sites on land and offshore. To get Communist acquiescence, JCRC would not be based in South Vietnam.1 Being aware of the many challenges to mission accomplishment in 1973 will help one understand why many of the same problems still plague POW resolution teams today.

Some background on the American wartime personnel recovery program will precede an explanation of how JCRC evolved, its organizational structure, and mission. Several sequential temporary assignments in 1974 gave MAJ Mather ‘hands on’ roles in the operational cycle of field MIA resolutions. These led to the recovery of a Special Forces (SF) officer, MAJ George Quamo, Deputy Commander, Command and Control North (CCN), U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), Special Operations Group (SOG), and two more Americans in Hue. Quamo led the CCN relief force to rescue the survivors of the Lang Vei SF Camp after it was overrun 7-8 February 1968 by a succession of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) sapper-infantry-tank attacks. While U.S. servicemen were fighting, dying, and being wounded in SEA, their homeland was being torn asunder by massive social unrest country-wide.

The Vietnam War hardened American public attitude towards its military prisoners and those missing in action. While the U.S. government unceremoniously withdrew its combat troops in 1972 after fighting its longest war, a grass roots movement to organize the POW families and missing in SEA garnered serious political clout. Mrs. Sybil Stockdale, wife of Commander (CDR) James B. Stockdale (U.S. Navy pilot shot down 9 September 1965), formed a National League of Families of American Prisoners and Missing in Southeast Asia (short title: National League of Families) that year. It quickly attracted popular support (most memorably by the sale of by-name Prisoner of War [POW]/MIA identification [ID] bracelets).4 The National League of Families became the single greatest focal point between the American electorate and the Nixon administration.”5 The families were demanding answers.

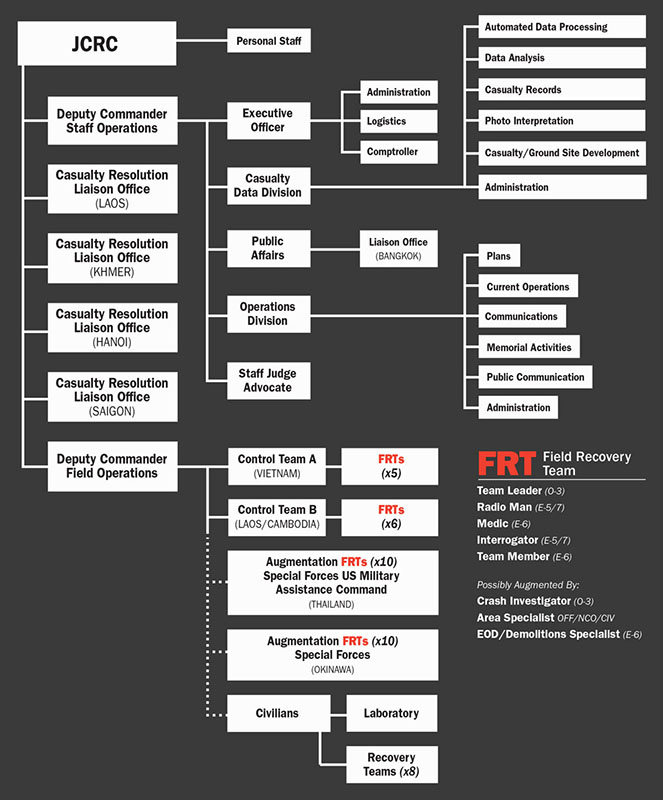

Prompted by League of Family pressure on the Defense Department, PACOM, which had directed the military fight in South Vietnam, began creating JCRC to find, recover, identify, and repatriate more than 2,500 American military and civilians MIA in Southeast Asia (SEA).6 The locations of the preponderance of unresolved losses differed by service: Air Force, Laos (363) and North Vietnam (358); Army (522) and Marine (217) MIAs and BNRs, South Vietnam; and Navy losses at sea (173) and over land (233--most in North Vietnam).7 Improved forensics and DNA identification in the mid 1980s enabled medical pathologists and physical anthropologists to resolve MIA cases exponentially.8 This new organization, JCRC, should not be confused with its wartime antecedent that had similar initials, the Joint Personnel Recovery Center (JPRC).

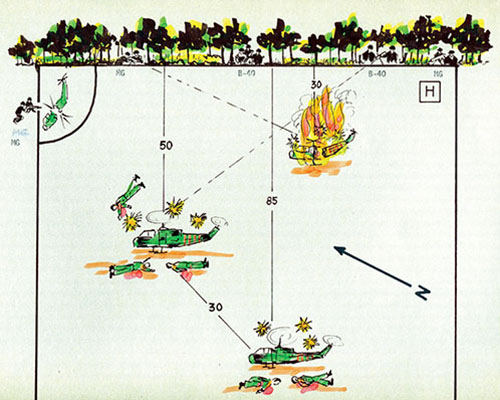

JPRC, formed 17 September 1966 by MACV, was assigned to SOG. Its mission was to coordinate the rescue of imprisoned, detained, escaped, and evading U.S. military and civilians and allied troops when air and ground search and rescue (SAR) efforts were ended in South and North Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand.9 JPRC collected MIA information because the Communists would not identify the American POWs. “The ad hoc approach to formalization of the process in the early years was at best a patchwork fix for what became the most emotional aspect of the war,” recalled Colonel (COL) William H. Jordan.10 Two weeks before MACV disbanded SOG (April 1972), the ten assigned JPRC personnel and their MIA records were transferred to the Director of Intelligence, J-2.11 As U.S. military units began withdrawing from South Vietnam, five people in the Joint Graves Registration Office, Saigon were assigned to JPRC.12 At the end of November 1972, JPRC (now up to sixty personnel) was provisionally called JCRC. Former emphasis on those possibly alive shifted to the dead after the POWs were released.13 Less than a month later, PACOM authorized 110 personnel to raise the number of field recovery teams (FRT)* to eleven.14 By then, recruiting was going ‘full bore’ in Saigon.

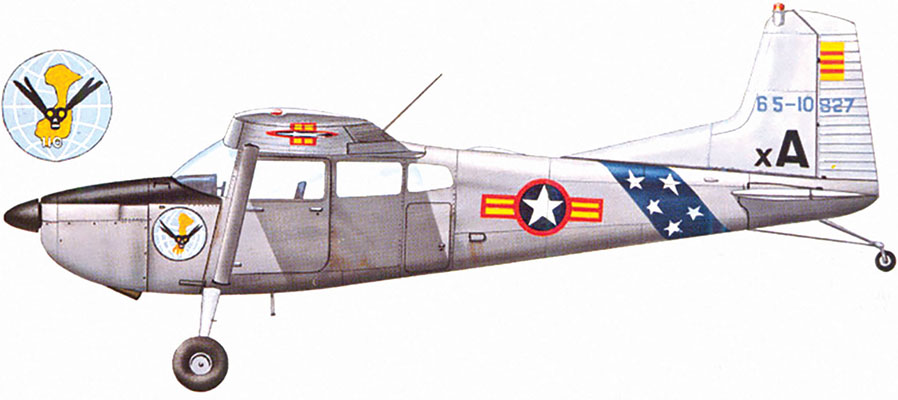

In 1973, MAJ Paul Mather, the Army-trained PSYOP officer, was an engineer advisor in the Civil Operations and Rural Development Support (CORDS) program under MACV. CORDS was rebuilding rural security and confidence in the South Vietnamese government province by province. Facing curtailment of his second tour (no career credit) because of mandated military drawdowns, Mather volunteered for the JCRC PSYOP position. As that organization matured in a tenuous environment the Air Force major did more than PSYOP. He became the ‘institutional memory’ of JCRC. Based on experience spanning fifteen years, Paul Mather wrote the seminal book on the topic, M.I.A.: Accounting for the Missing in Southeast Asia, in 1994.15

Charged with resolving the status of America’s 2,500 MIA and MIA/BNR, JCRC was activated on 28 January 1973 at Tan Son Nhut Air Base (VNAF [South Vietnamese Air Force]) by Brigadier General (BG) Robert C. Kingston. After being interviewed by BG Kingston, those accepted for assignment were transferred to Thailand.16 The new joint element would be located on Nakhom Phanom (NKP) Royal Thai Air Force Base in northeast Thailand. The Joint Graves Registration Office and the U.S. Army Mortuary, Saigon (Tan Son Nhut Air Base), the U.S. Air Force Mortuary at Da Nang and the Central Identification Laboratory (CIL), were consolidated, renamed CIL/Thailand, placed under the operational control (OPCON) of JCRC, and moved to Camp Samae San on Utopai Royal Air Force Base, southeast of Bangkok.17 CIL/THAI, led by Quartermaster (QMC) Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Harold Tucker, became operational on 23 March 1973.18 Both units were filled with personnel from the U.S. military, civil service, and contract employees slated to leave South Vietnam in accordance with the Paris Peace Accords.19