NOTE

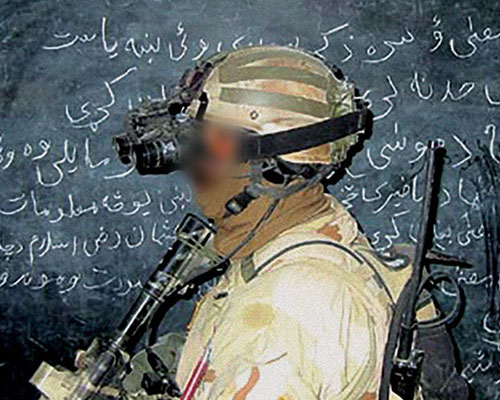

IAW USSOCOM Sanitization Protocol for Historical Articles on Classified Current Operations, pseudonyms are used for majors and below who are still on active duty, unless names have been publicly released for awards/decorations or DoD news release. Pseudonyms are identified with an asterisk (*). The eyes of active ARSOF personnel in photos are blocked out when not covered with dark visors or sunglasses, except when the photos were publicly released by a service or DoD. Source references (end notes) utilize the assigned pseudonym.

This article incorporates new material into an early account initially published in Weapon of Choice: ARSOF in Afghanistan.1 That book was the first official Army history of that conflict to be published and it established procedures for ‘sanitizing’ combat accounts of classified articles. This updated text and accompanying photos and maps support the USASOC commander’s desire to emphasize early Special Forces experiences conducting counter-terrorist operations in Afghanistan. There remains a wealth of information to learn from those operations.

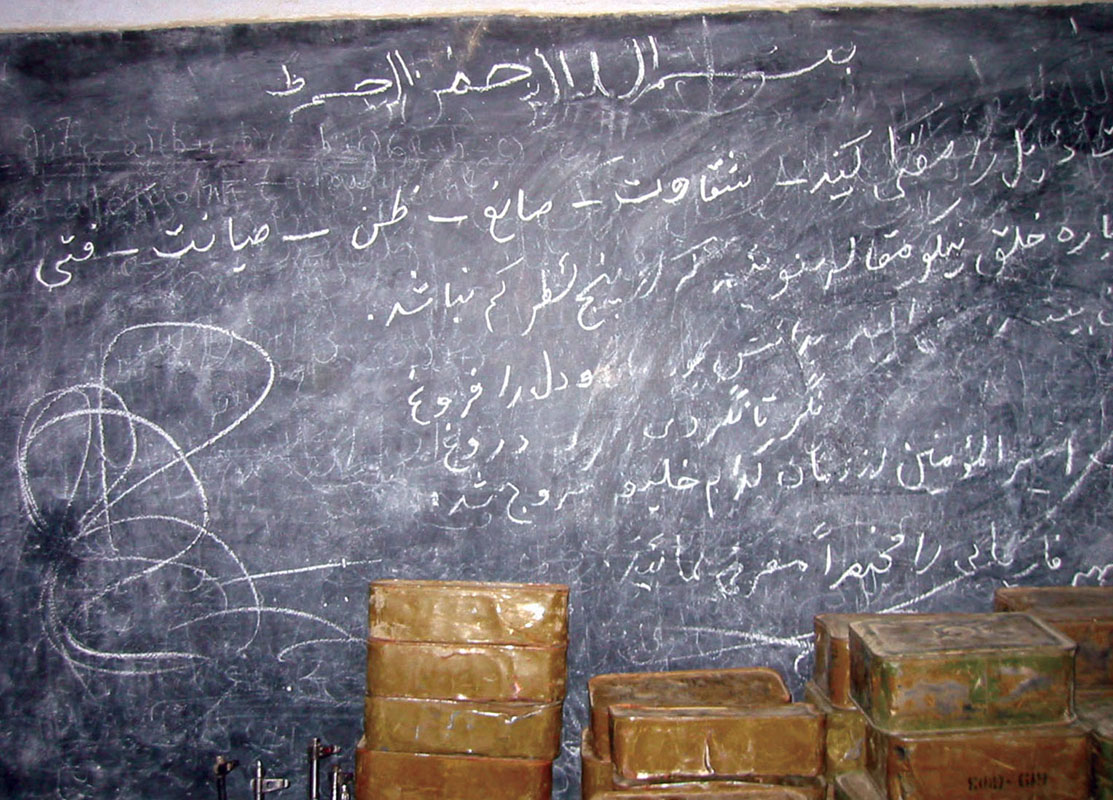

As the hunt for Osama bin Laden and the al Qaeda leadership continued in Afghanistan through the winter of 2001-2002, U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) directed a discrete intelligence-gathering mission that required the long-range reconnaissance and surveillance and urban warfare close-quarters battle skills of Company A, 1st Battalion, 5th Special Forces Group (SFG) (A/1/5).2 This mission was referred to as a sensitive site exploitation (SSE), and it called for the focused search and recovery of enemy personnel, documents, manuals, monies, computers, communications equipment, explosives, weaponry, and related materials that might be of intelligence value.3

Commanded by Major (MAJ) Jon West* (pseudonym), A/1/5 was specifically organized, trained, and equipped for this type of mission. The company supported USCENTCOM on particularly complex long-range reconnaissance and surveillance and direct action (DA) missions—raids and surgical strikes—predominantly in urban or built-up areas. All unit members were highly trained in the skills of close-quarters, room-to-room fighting; long-range surveillance; and sniping.4

Since December 2001, A/1/5 had conducted three SSE missions with marked success. Surprise was so complete and execution so rapid that only two shots had been fired in all three missions—both warning shots prompting immediate surrenders. The company captured nine al Qaeda suspects (detainees); destroyed several tons of weapons and ammunition; and made valuable intelligence finds, including satellite telephones, tape recordings, and encrypted electronic records.5

On 9 January 2002, the Combined Forces Land Component Command (CFLCC) of USCENTCOM issued another SSE order to U.S. Navy Captain Robert S. Harward, commander, Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-South (CJSOTF-South), then based at Kandahar Airport.6 CFLCC tasked CJSOTF-South to conduct an SSE of two suspected al Qaeda compounds at Hazar Qadam near the town of Oruzgan, 166 km northeast of Kandahar in mountainous Oruzgan Province. The mission, designated “AQ-048,” was to kill or capture any Taliban or al Qaeda personnel and collect material for intelligence analysis.7

The intelligence staff at CENTCOM disclosed two target sites to CFLCC. Each walled compound contained a collection of various-sized buildings. The compounds were surrounded by orchards and farm fields, and the two sites were 1.5 km apart. When the photo interpreters suggested that there might be women and children in the compounds, planners ruled out a ‘kinetic strike’ (aerial bombardment) and directed a ground raid. Because of the size and complexity of the two sites, Captain Harward selected A/1/5 for the SSE mission and attached a New Zealand Special Air Service (SAS) unit.8

MAJ West* decided he would seize both sites simultaneously and divided his company into two assault forces. New Zealand SAS troops were designated as a quick-reaction force (QRF) in the event more combat power was needed. West* would lead Special Forces Operational Detachments Alpha (ODAs) 512, 513, and 514 in an assault of the westernmost site, named Objective KELLY. The eastern compound, designated Objective BRIGID, became the target for ODAs 511 and 516, led by the company operations officer, Chief Warrant Three (CW3) Dwight Ashford.*9

Each force would have sufficient radio operators, explosive ordnance demolition (EOD) experts, interpreters, and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents attached. The FBI agents would select those detainees they wanted for questioning and also assume ‘chain of custody’ responsibility for all evidence collected to ensure admissibility in any subsequent legal proceedings. If necessary, they would also serve as government witnesses in the event of suspects being charged with crimes in a U.S. court.10 At this early stage in the conflict that was still a consideration.

To avoid establishing predictable operational patterns in executing their mission, MAJ West* arranged for helicopters to infiltrate the assault forces at night into separate remote landing zones (LZs) several kilometers (km) away from the objectives. The high-altitude mountain valley LZs were hidden from Hazar Qadam by intervening ridges. Those features also masked the sound of the helicopters as they flew nap-of-the-earth (NOE) routes that skimmed along the bottom of valleys and popped over passes. After landing, Ashford’s mobile force, wearing night-vision goggles (NVGs), would drive 6 km on a dirt road to Objective BRIGID in two heavily-armed high-mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicles (HMMWVs), or ground mobility vehicles (GMVs).11 West’s* three Special Forces teams, also wearing NVGs, would walk 5 km around a mountain peak to approach their target, Objective KELLY.12