DOWNLOAD

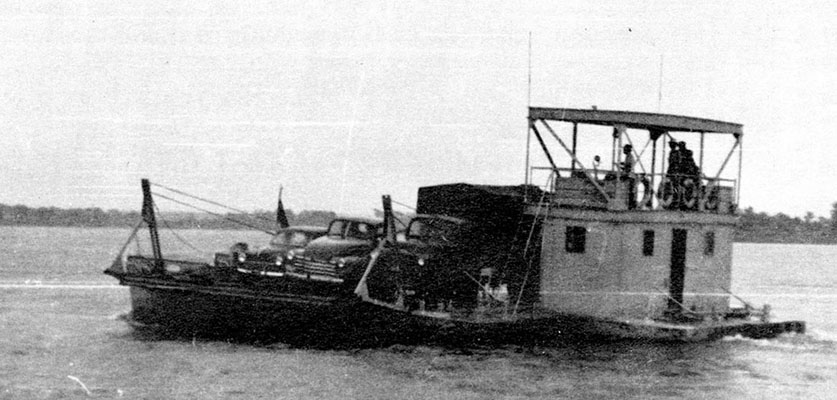

In the wake of independence from Belgium on 30 June 1960, law and order collapsed in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Force Publique mutinied on 8 July, the two richest mining provinces, Katanga and Kasai seceded (July and August respectively), and tribal strength trials among government leaders never stopped.1 Mistrust, suspicion, and bitterness towards Belgians grew daily among the Congolese tribal factions and political groups.2 White Europeans became targets for racial attacks and a panic-stricken exodus began. In response, the Belgian government convinced Sabena World Airlines to divert aircraft to evacuate its citizens from the Congo.3 To support that internationally maligned effort, a U.S. European Command (USEUCOM) aviation task force (TF), clandestinely directed by three Special Forces (SF) soldiers, rescued 239 American and foreign missionaries, doctors, and nurses from rural areas experiencing rampant lawlessness.4 Mission success can be attributed to the timelessness of SF operational capabilities and flexibility in adapting to rapidly changing situations.

The purpose of this article is to detail a formerly sensitive, classified rescue mission that was conducted by 10th SF Group (SFG) in July 1960.6 It was the first operational tasking given to SF by U.S. Army, Europe (USAREUR), a service command of USEUCOM which was dominated by heavy conventional forces (armor, mechanized infantry, and armored cavalry). Its success demonstrated the ‘value added’ of Special Forces to the command, and reminded North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) partner nations of their capabilities. The U.S. Air Force overt airlift of refugees, UN peacekeeping forces, food, equipment and medical supplies has long garnered the most publicity.7

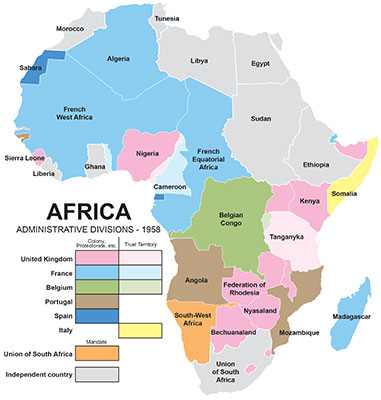

To understand what prompted this 10th SFG-led humanitarian rescue mission, some pre-independence background and key facts and figures on society, politics, and economic factors are necessary. Maps, charts, and sidebars cover geography, concurrent world events, population, tribal groups, religious distribution, and identify key Congolese politicos: Patrice E. Lumumba; Antoine Gizenga; Joseph Kasavubu; Joseph D. Mobutu; and Moïse K. Tshombe. The reader must bear in mind that activities in Africa moved quickly in the early 1960s. Current status one day was history two days later, especially in the political and social arenas of this very turbulent period.8 Hence, period sources are used for context. This article is divided into four sections: Post-Independence, which provides the background; the Special Forces Mission; an Epilogue summarizes the first two years after UN intervention; and the Postscript discusses awards, post-operation security constraints, and rationale behind the SF success in 1960.

“Almost all Europeans in the Congo at this time were apprehensive if not alarmed; though many of us felt that some troubles and minor incidents were bound to occur, a general racial struggle was not foreseen.” - Alan P. Merriam, Congo: Background of Conflict (1961)5

Belgian Congo

Post-Independence in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

Violent racial-economic riots broke out in Leopoldville, the capital of the Belgian Congo, in January 1959. This upheaval preceded internal tribal fighting in Kasai province that spread to the capital in May 1960. Belgium’s inability to resolve these problems reinforced anti-colonial attitudes in America and the United Nations. These dilemmas prompted young King Baudouin I to accelerate the transition to independence of their African colony.9 While the world media heralded nationalism with independence, tribal blocs in the Congo defined politics. Since no tribe had a majority, their political leaders vied for key government positions. Simultaneously, newly-elected legislators voted themselves pay raises and health benefits with little concern for the state’s financial solvency. A four-day holiday to celebrate independence was approved unanimously. These were heady times for Congolese. Dreamlike expectations were the norm.

The U.S. News & World Report correspondent on the scene, David Reed, described the situation: “When the blacks took over from the Belgian colonial administrators, they were far from ready to govern. African officials suddenly were big shots, rode around in fancy cars, and took over elaborate homes. In short, they replaced a white aristocracy with a black aristocracy. When the African soldiers of the Belgian-officered Force Publique saw what was happening, they wanted their share. The Premier (Patrice Lumumba) did not deliver his pre-independence promises. The troops went crazy and turned on whites to vent their frustration and rage.”10 The three-man International Staff team from that news magazine repeated the same observations in the 8 August 1960 issue. As authority broke down, senior white civil servants who knew how to make the government operate panicked and ran for their lives. When white business directors, industry managers, and technicians followed suit, the economy collapsed.11