NOTE

*All photos in this article are from the National Archives.

DOWNLOAD

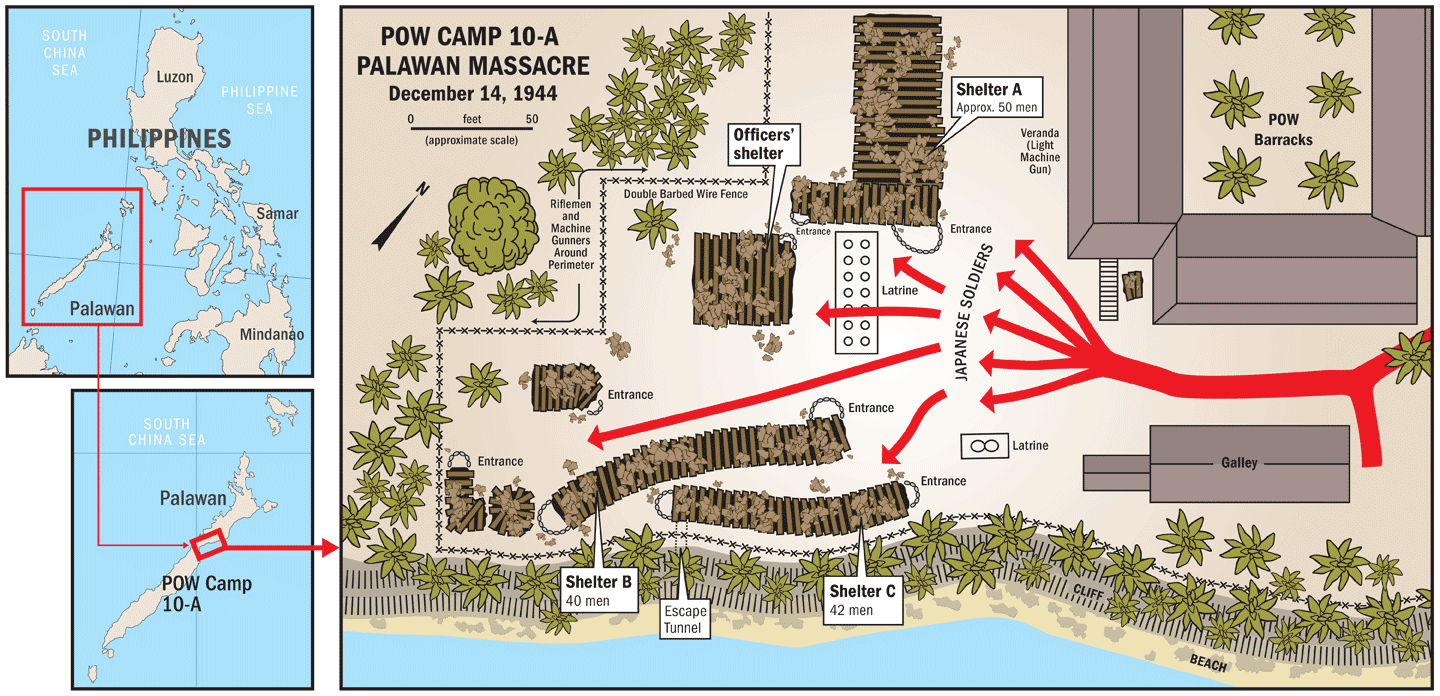

After three years of brutal captivity under the Japanese, the 150 American inmates of prisoner of war (POW) Camp 10-A on the western Philippine island of Palawan had developed an instinct for recognizing the abnormal. For several months in late 1944 the Palawan POWs had worked hard to build a runway for the Japanese Army. Lately, their duties included repairing damage caused by almost daily U.S. bombing attacks.1 As 1944 came to an end, many of the prisoners noticed changes in the demeanor of their guards. The Japanese had become increasingly short-tempered and imposed cruel punishments for the slightest of infractions. On the morning of 14 December 1944, the POWs’ sense of dread reached new heights.2

This short article reveals the details behind an incident that pushed military leaders in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) to plan action to prevent similar occurrences. The Palawan Massacre so horrified senior leaders that references to the atrocity were kept classified to maintain high morale among the forces preparing to invade the Philippines.3 Despite these precautions, word spread quickly as evidence of the incident and others just as grisly. Leaders decided to act and to rescue prisoners, detainees, and internees from similar fates.

On that fateful morning of 14 December the guards roused the prisoners at 0200 hours, far earlier than normal. At the airfield before work the POWs saw more guards than usual. Many chalked it up to pre-invasion jitters because the Allies had been bombing Japanese bases in preparation of an invasion. The laborers were ordered to repair damage and improve the airstrip. As he was working to fill a bomb crater, Marine Corporal (CPL) Rufus W. Smith turned to his long-time friend, CPL Glenn W. McDole, and said, “Something is going on, Dole. What the hell do you think is happening?”4 As they labored under the rising hot sun, other POWs wondered as well.

At 1100 hours the guards signaled a sudden halt to work and began roughly herding the prisoners toward one side of the runway. There, atop a small wooden box stood a familiar Japanese officer, Lieutenant Yoshikazu Sato. Sato, known to the prisoners as the ‘Buzzard,’ waited until his guards had formed the prisoners in ranks. Then, he ominously announced, “Americans, your working days are over!” With that abrupt announcement, the guards herded the prisoners onto waiting trucks.5