NOTE

Pseudonyms in the official Colombian Government account by Juan Carlos Torres, Operación JAQUE: La Verdadera Historia (2008), have been used in this article and endnotes.

TAKEAWAYS

- The OWS EXORD provided expanded authorities needed to improve COLMIL capabilities and capacity to locate and recover the Americans hostages held by the FARC.

- BG Charles Cleveland, the SOCSOUTH commander, made finding and rescuing the hostages his top priority; he operationalized OWS by establishing a SOC-Forward in Bogotá.

- SOCSOUTH adroitly used the OWS EXORD, NSPD-12, and Section 1208, National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) to get dedicated national intelligence assets and forces.

- Providing counterterrorist (CT) training to COLSOF enabled COLMIL to take direct action against FARC leaders.

- The PSYOP campaign created dissent in the FARCranks and encouraged defections.

DOWNLOAD

The strong American military relationship with Colombia dates to the Korean War. This partnership is a model of U.S. Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) long-term engagement. Since the 1980s, the United States has provided significant support to Colombia and other South American countries to attack cocaine production at its source. Plan Colombia (1999), presented in English to the U.S. Congress by President Andrés Pastrana Arango, was designed to contain the drug problem in that country. Unfortunately, his demilitarized FARC-landia plan backfired. In the wake of 9/11, a charismatic Colombian President Álvaro Uribe Vélez convinced the American legislators that Plan Colombia could also restore legitimacy to insurgent-controlled areas in his country, particularly FARC-landia.1

U.S. funding was increased, and training support was extended beyond the National Police to the new Colombian Army (COLAR) Counter-Drug battalions. The mobility afforded by organic helicopter fleets was key to better successes in the mountainous country—twin-engine UH-1N Hueys and UH-60L Black Hawks were provided as security assistance.2 America’s Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) proved a boon to her allies.3

U.S. National Security Presidential Directive 18 (NSPD-12) labeled the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia), the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN), and Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) as terrorist organizations in 2002. This enabled the U.S. military to increase intelligence sharing and support Colombian counter-terrorist (CT) operations.4 However, the counter-drug mission would continue to dominate the American effort in Colombia. The State Department (DOS) contracted DynCorp for aerial spraying and coca eradication while the Department of Defense (DoD) contracted SOUTHCOM Reconnaissance Systems (SRS), a subsidiary of Northrop Grumman, to conduct aerial surveillance of coca-producing regions.5

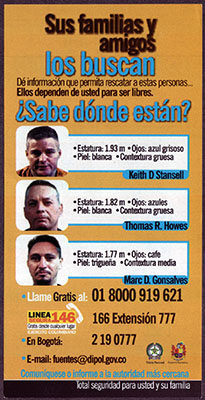

While the FARC had been taking hostages for decades (more than 500 military, police, and local government officials) for ransom and political negotiations, it was not until they seized three American SRS contractors (Marc D. Gonsalves, Keith D. Stansell, and Thomas R. Howes) that Washington had to deal with the problem. Their SRS single-engine Cessna 208B Caravan developed engine problems and crash-landed near the Cordilleria Oriental mountain range, south of Bogotá on 13 February 2003. The FARC executed the injured pilot, retired CW5 Thomas J. Janis, a Vietnam veteran helicopter pilot, and the COLAR observer, Sergeant (SGT) Luis Alcides Cruz, before the terrorist group disappeared into the heavy jungle with their three U.S. hostages.6

U.S. Army Special Forces (SF) training the COLAR and National Police monitored the aircraft distress radio traffic. They were working 30 minutes Black Hawk helicopter flight time from the crash site, but were not allowed to join the Colombian aerial response. U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) rules of engagement (ROE) did not permit American SOF to accompany host nation (HN) forces into FARC-dominated territory.7

Why not? Latin America had not been designated as a U.S. theater of combat operations. Since SF could not engage in direct combat, there was no U.S. military (USMIL) personnel recovery (PR) plan, nor a quick reaction force (QRF). Since FARC strength in the crash site area was unknown, the American ambassador, Anne W. Patterson, and the Special Operations Command, South (SOCSOUTH) commander, Brigadier General (BG) Remo Butler, recently relocated to Puerto Rico from Panama, were reluctant to request authority to commit U.S. forces in Colombia. To further complicate matters, the U.S. policy on hostages did not specify that American citizen (AMCIT) contractors were considered U.S. Government (USG) personnel nor contain anything about assisting in their recovery.8 With no additional information the fate of hostages was unknown. ‘Proof of life’ would not come for several months.9

Meanwhile, the SRS contract flight team continued to search for their lost members between drug surveillance missions. They flew the remaining Cessna Caravan until 25 March 2003, when it clipped a tree and crashed in a ravine. The two pilots, James Oliver and Thomas Schmidt, and the sensor technician, Ralph Ponticelli, were killed. That ended the SRS effort.10

Washington officials used NSPD-12 to prevent family members from contacting the FARC. The official U.S. policy was not to negotiate with terrorists.11 Ironically, the official status and rights of USG contractors and USG responsibilities for them had never been delineated despite a proliferation of contractors on ‘battlefields’ dating to the First Gulf War (Operations DESERT SHIELD/STORM) in 1990-1991.12

The plight of three Americans held captive in the jungles of Colombia became obscured by the start of Operation IRAQI FREEEDOM (OIF) in 2003, while Operation ENDURING FREEDOM (OEF) continued in Afghanistan and the Philippines (OEF-P).13 In addition, the SOUTHCOM headquarters in Miami was heavily engaged with stability operations in Haiti, and the SOCSOUTH headquarters was departing Puerto Rico for Homestead Air Reserve Base in Florida. Officially, SOCSOUTH could only saturate FARC-controlled areas with ‘Rewards for Justice’ leaflets seeking information on the status of the three Americans. The Department of Justice and the U.S. ambassador approved the messaging on these leaflets. ‘Proof-of-life’ was finally received in July 2003. Colombian journalist Jorgé Enrique Botero videotaped his interviews with the captured Americans and former Senator Ingrid Betancourt Pulecio and her campaign manager/vice presidential running mate, Clara Leticia Rojas González. The latter two had been seized on 23 February 2002 while campaigning for the presidency in the Switzerland-sized demilitarized zone of Colombia called FARC-landia.14

Ironically, two months before Botero was given access to the VIP hostages a U.S. Special Operations Forces (USSOF) CT-trained Colombian SOF (COLSOF) element attempted a daylight direct action rescue assault in the jungle. It failed miserably. Upon hearing the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters hovering as the COLSOF assaulters ‘fast roped’ to the ground, the FARC commander ordered his hostages shot. Nine were killed and three wounded (one fatally). Amazingly, one survived unscathed. Remember, FARC units had to guard, feed, and constantly move 500 plus hostages in the jungle-clad mountains. President Álvaro Uribe Vélez took full responsibility for the debacle in a nationally televised address.15 Afterwards, the possibility that a senior Colombian leader would authorize a direct action hostage rescue in the jungle became very remote. The fact that the Colombian military (COLMIL) leadership had categorized direct action rescue as nonviable in 2002 was either unknown, or it was lost on SOCSOUTH.16

Subsequent electronic warfare (EW)/signal intelligence (SIGINT) radio intercepts revealed that FARC leaders had increased security measures and directed hostage executions when rescue was imminent. For example, an accidental encounter between two different FARC elements in the dense jungle led to a firefight and hostages were executed.17 After the 2002 hostage rescue fiasco, COLSOF redirected their direct action against narco-traficante and terrorist leaders (high value targets [HVT]) to disrupt organizational command and control.

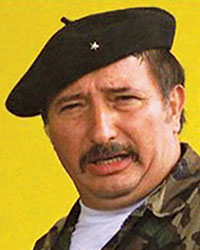

Despite a dearth of actionable intelligence on the whereabouts of the American hostages from 2003-2005, COLSOF did well against HVTs. This effort supported the suggestion of BG Charles T. Cleveland, subsequent SOCSOUTH commander, who recommended that the FARC leadership be inundated with ‘dead or alive’ rewards and specific targeting. He wanted to keep them ‘off balance’ and feed their paranoia about security.18 COLMIL opened communications with the FARC hostage holding groups with their radio program that weekly broadcast family messages (‘El Voz de Secuestrados’ [Voice for the Abducted]). Allowing the captives to listen was a morale booster. FARC commanders adjusted their routines to accommodate broadcasts.19 After a thorough assessment of the American hostage recovery situation to date, the newly-appointed ambassador, William B. Wood, cabled the White House in November 2004 to request it be given a higher priority.

Army General (GEN) Bantz J. Craddock, the SOUTHCOM commander, shared the ambassador’s request with the Secretary of Defense and directed his staff to draft an execution order (EXORD) for Operation WILLING SPIRIT (OWS). ‘Leaning forward,’ DoD authorized SOUTHCOM to participate in combined (non-combat) sensitive site exploitation (SSE) operations (crime scene forensics) on HVT camps recently targeted by COLSOF. Approval for USSOF to accompany COLSOF reconnaissance teams into FARC-controlled regions was withheld. It was May 2005 when the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) approved the OWS EXORD. It had guidance, authorities, and granted access to national defense and intelligence resources to expedite locating and rescuing the American hostages. New ROE also allowed more direct support to the COLMIL.20

However, the expanded ROE did not apply to USSOF already committed to counter drug training and military assistance. Despite the OWS EXORD, operations in the SOUTHCOM area of responsibility (AOR) remained an economy of force effort. However, when the ARSOF BG Charles T. Cleveland took command of SOCSOUTH in June 2005, he announced that his top priority was the recovery of the American hostages in Colombia.21

As Executive Agent for OWS, BG Cleveland adroitly leveraged the authorities in the OWS EXORD, NSPD-12, and Section 1208 of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) to build greater COLSOF capacity and improve capabilities. Capitalizing on the successes of combined SSE missions, he requested that GEN Craddock authorize the ‘imbedding’ of USSOF personnel with COLSOF reconnaissance teams working in FARC areas. Capitalizing on his personal and professional relationship with Colonel (COL) Simeon G. Trombitas, Military Group (MILGP), Colombia commander, and the MILGP commander’s access to Ambassador Wood, BG Cleveland requested and was allowed to put a small SOC-Forward (SOC-FWD) element in Bogotá to ‘operationalize’ the OWS EXORD.22

In the meantime, the SOCSOUTH staff at Homestead Air Reserve Base, Florida, prepared a regional ‘playbook’ for the high priority countries of Latin America. The Colombia section was the most developed. It had hostage recovery contingencies and assorted task force packages. Among them was a unilateral U.S. direct action rescue option with COLMIL support. SOCSOUTH took this option seriously. It was first rehearsed in Florida before being exercised with COLAR elements at the John C. Stennis Space Center in Mississippi.23

COLMIL capabilities and COLSOF capacity had improved significantly with General Cleveland’s command emphasis, combined partnering initiatives, information sharing, and the SOC-FWD presence. In June 2006, COLAR SIGINT intercepted a message that the FARC VIP hostage group with Ingrid Betancourt and the Americans had been given permission to relocate to Yari province. Combined reconnaissance (recce) teams were launched. These teams were to ‘find and fix’ that FARC element location and positively identify the hostages. Despite a lot of COLSOF/SOCSOUTH efforts, the COLAR-dominated Operación CENTURIÓN accomplished little more than demonstrating a compatibility for combined operations under OWS.24

Sophisticated aerial search platforms were thwarted by the dense, triple canopy jungle-covered mountains of Colombia, especially at night.25 COLAR human intelligence (HUMINT) was still minimal because relations with the National Police remained fractured by a competition for resources.26 The FARC element with the VIP hostages was not located, but they were always at the top of essential elements of information (EEI) assigned to the recce teams.27