DOWNLOAD

On 24 March 2003, 2nd Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group (FOB 102), occupied the western half of Joint Special Operations Task Force (JSOTF)-North’s area of responsibility. Situated along the Green Line, the tentative demarcation boundary between the Kurdish Autonomous Zone and Iraq to the south, 2nd Battalion faced four dug-in and well-equipped divisions of the Iraqi 5th Corps. Covering a two-hundred-kilometer front with little more than light antitank weapons, limited close air support (CAS), and assistance from their Peshmerga allies, FOB 102’s dual mission was to defend the north, and to keep as many Iraqi troops as possible focused on them and not on Baghdad.1

Second Battalion accomplished the mission by dividing the front into three company sectors: Advanced Operating Base (AOB) 050 to the west in Dihuk, AOB 370 in Aqrah, and AOB 040 to the east in Irbil. Within these sectors, the companies observed seven targeted areas of interest covering the main avenues to the south. During an initial defensive phase, which lasted approximately a week, FOB 102 watched the Iraqi positions from its observation posts and called in CAS to degrade the enemy threat.2

During the first few days of April 2003, FOB 102 and their Peshmerga counterparts took the offensive. While advancing south, they liberated numerous villages and steadily drove the enemy toward the urban centers of Kirkuk and Mosul. In some cases, progress was unopposed and rapid, the enemy having abandoned his positions following the devastation wrought by successive air attacks. In others, they encountered a determined enemy who not only fought to retain terrain, but also launched multiple counterattacks to reclaim what had been lost. Perhaps the most intense resistance faced by FOB 102 was in Debecka, on 6 April 2003.3

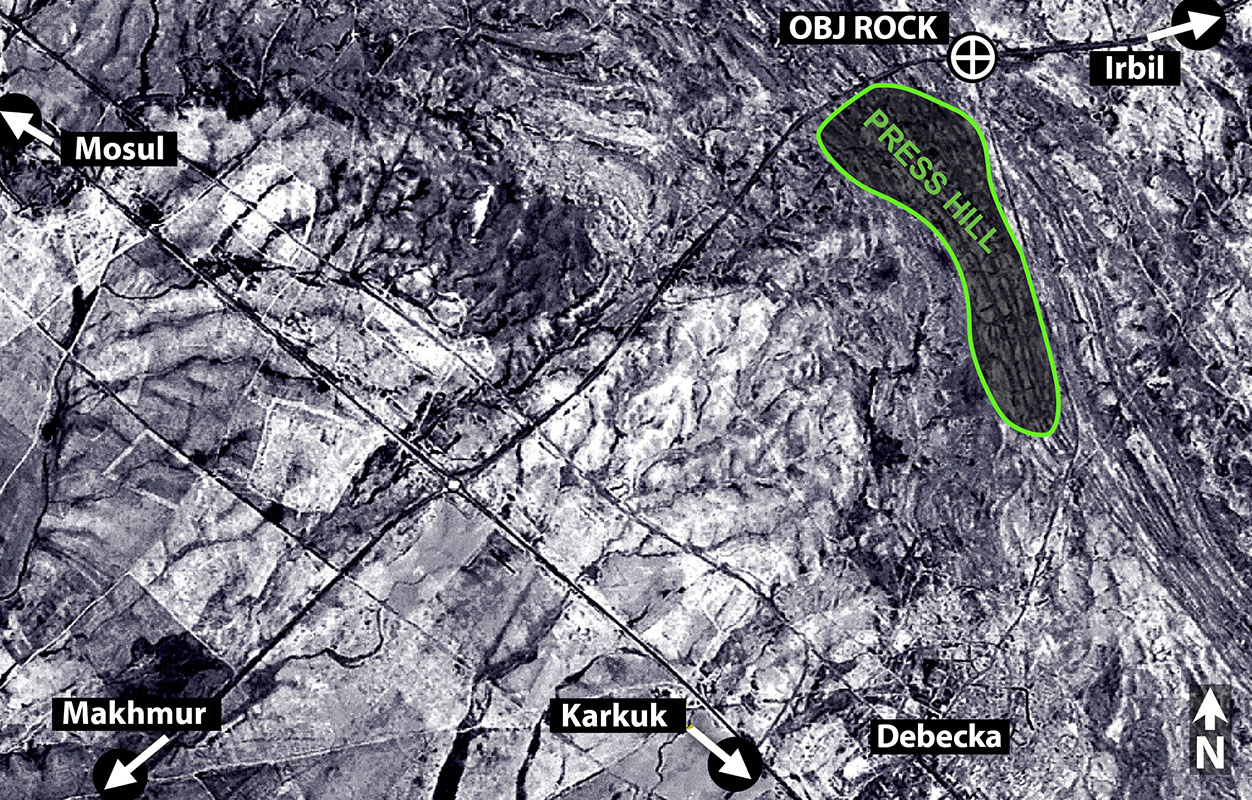

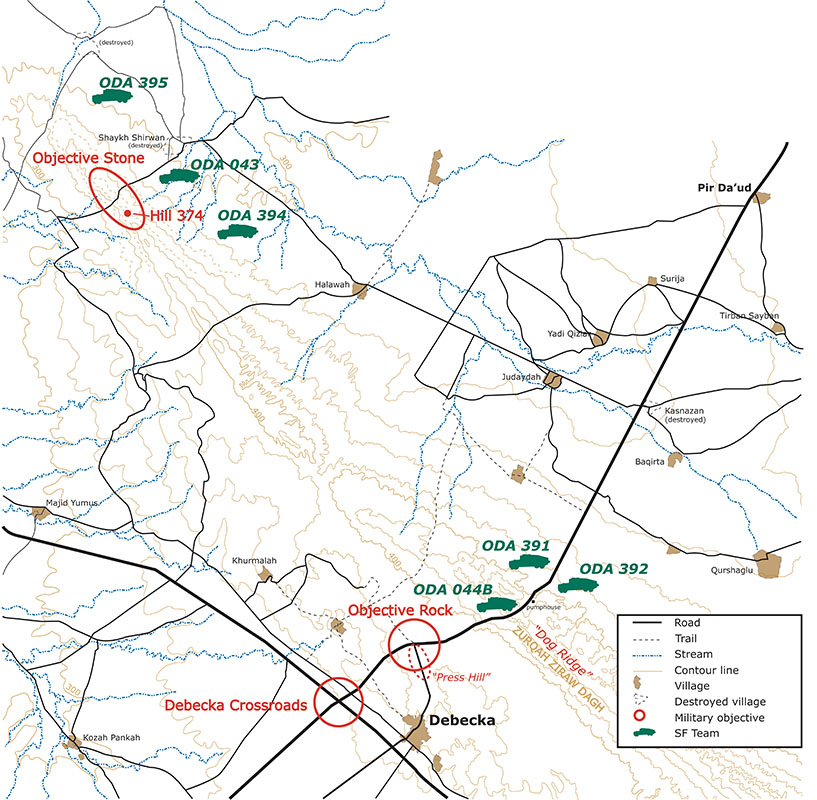

The town of Debecka, located forty kilometers south-southwest of Irbil, sits to the southeast of a four-way intersection where the roughly northeast–southwest road from Irbil to Al Qayyarah meets the northwest–southeast road from Kirkuk to Mosul. Approximately three kilometers northeast of the main intersection, a bypass road leads off the Irbil–Qayyarah road back into the northwestern section of the town, which sits on the Kirkuk–Mosul road. Still further to the northeast, approximately five kilometers from the crossroads, is Zurqah Ziraw Dagh Ridge. Referred to by Americans as “Dog Ridge,” it is 110 kilometers long and 400 meters high, and is bisected by the Irbil–Qayyarah road. On the northeast side of the ridge, twenty kilometers from the crossroads, is a small village named Pir Da’ud, where Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) 044 established an observation post during the initial stages of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM.4

According to intelligence reports, Iraqi forces had occupied positions along the northern base of Dog Ridge as recently as two days before ODA 044’s arrival, when the enemy displaced to the crest of the hill. During the days preceding the attack on Debecka Crossroads, ODA 044 was able to observe Iraqi soldiers manning mortar, heavy machine gun, and antiaircraft artillery positions. Although the team’s exposed position was subject to enemy artillery and rocket fire, it retaliated by calling in CAS and drove the Iraqis back to the southwestern face of the ridge.5

On 5 April 2003, as the threat lessened and the likelihood of a successful assault increased, the local Peshmerga commander announced that he was going to attack the ridge and had already sent engineers to clear the road of mines. Shortly thereafter, the Special Forces (SF) soldiers heard the sound of small arms fire and exploding artillery rounds near the ridge. The Peshmerga were compelled to abandon their assault, and for the next three hours, the Iraqis shelled several local villages in retaliation. Later that evening, Major (MAJ) Eric Howard, AOB 040’s commanding officer, met with General Mustafa, the Kurdish Democratic Party commander of the Western Military District. They discussed the necessity of seizing the ridge and agreed that a coordinated coalition attack would commence the next day.6

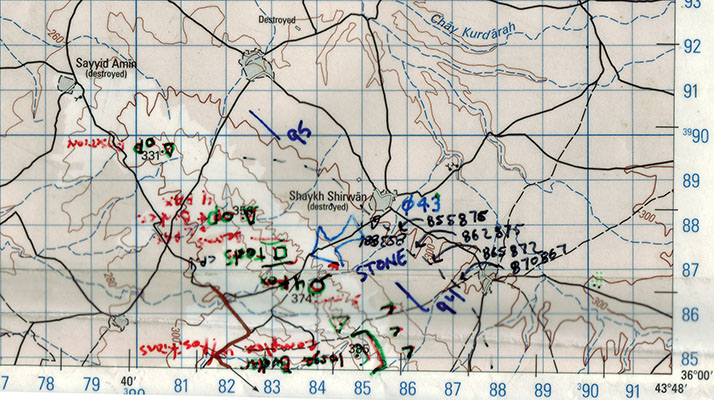

The assault force assembled in Pir Da’ud that night to prepare for the attack. In addition to ODAs 043 and 044, four ODAs from FOB 33 had also arrived to support the attack with gun-mounted Ground Mobility Vehicles (GMVs). The plan was to soften the ridgeline with close air support that evening, cross the line of departure at sunrise, and launch four simultaneous assaults against the ridgeline. To the southeast, Sergeant First Class (SFC) Thomas Sandoval’s half of ODA 044 (044B) and 150 Peshmerga would attack the ‘T’ intersection formed by the bypass to Debecka and the Irbil–Qayyarah road north of Debecka—Objective Rock. ODA 391, led by Captain (CPT) Eric Wright, and ODA 392, led by CPT Matthew Saunders, would support the dismounted infantry with heavy machine gun fire. In the center, near Hills 419 and 429, two 250-man Peshmerga columns were to attack independently. To the northwest, CPT David Fowels’ ODA 043 and 150 Peshmerga would attack Hill 374, which was designated Objective Stone. To the north, ODA 394, led by CPT James Spivey, and ODA 395, led by CPT James E. Staton, would support the northwest assault by fire. Although aerial reconnaissance suggested that the ridge was lightly defended, prior contact with brigades from the Iraqi 1st Mechanized Infantry Division made the outcome of the attack far from certain. After the meeting, several ODA splits rolled south to watch for enemy activity, but only the sound of friendly CAS missions against the objective disturbed the evening.7

On 6 April, the coalition forces marshaled in the assembly area at 0600 local time. Although they did not cross the line of departure until 0700, an hour later than planned, progress was swift and the assault forces quickly reached their attack positions at the base of the ridge. The two independent Peshmerga columns met only limited opposition, and reaching their objective first, swarmed across the central portion of the ridgeline. However, the two flank columns faced much greater resistance and the assault became a battle.8

To the northwest, ODAs 394 and 395 waited in their GMVs for the CAS to do its job before moving into their designated support-by-fire positions. When the CAS arrived, only one of four bombs dropped hit the target. The teams then closed to within seventeen hundred meters and began to engage the enemy with MK19 40mm automatic grenade launchers and M2 .50 caliber machine guns. Before long, the Iraqis responded with their own heavy machine guns and mortars. Although the ODAs suppressed the objective for more than thirty minutes, expending approximately half of their ammunition, the Peshmerga refused to assault without additional CAS.9

Now in contact with the enemy, ODA 043 was able to get support from both U.S. Air Force B-52s and U.S. Navy F-18s. While ODA 043 coordinated the CAS missions, ODAs 394 and 395 used the distraction to disengage and withdraw four kilometers to the rear. Because they continued to receive 120mm mortar fire, they withdrew a second time and used the opportunity to refresh their ammunition supply. The teams then returned to the wadi where CPT Fowels and the Peshmerga prepared to assault the ridge.

Although ODAs 394 and 395 moved to resume their support-by-fire positions, rough terrain precluded swift vehicular movement and the assault force crested Hill 374 before the teams could bring their guns to bear. The Peshmerga quickly disposed of the Iraqi defenders, capturing several prisoners, mortars, and heavy machine guns.10

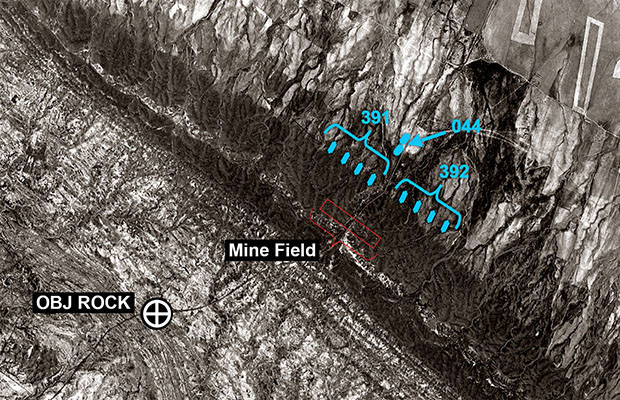

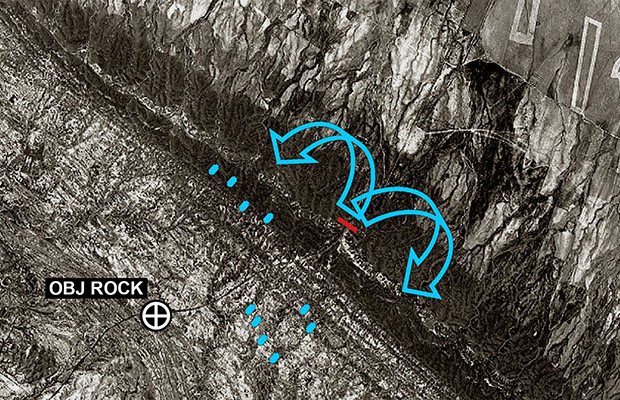

The teams led by SFC Sandoval, who served as the ground force commander for the southernmost objective, rolled together to the attack position at Kasnazan. This abandoned village was located midway between Pir Da’ud and a pump house at the base of Dog Ridge. As they continued on, using the road as a control feature, ODA 391 traveled along the northwestern flank, ODA 392 took the southeastern parallel, and ODA 044B and the Peshmerga took the middle. The mounted heavy gun teams operated in two vehicle sections, each armed with MK19s and M2 .50 caliber heavy machine guns. Each of the maneuver elements possessed its own forward air controller and, because he expected ODA 044B to meet the stiffest resistance, MAJ Howard granted it priority of fires.11

Although the original plan had been to return to the paved road once they had reached the base of the hill, the Iraqis had blocked the road with a large mound of earth and numerous land mines. After waiting fifteen minutes while the Peshmerga attempted to clear the obstacle, the ODAs decided to continue the advance cross-country. The teams forged ahead on goat trails that wound toward the top of the ridge, with ODAs 044 and 392 to the east, and ODA 391 to the west of the road.12

Although the assault force initially met only limited Iraqi resistance, once it reached the reverse slope on the southeast side of the road it encountered dug-in troops supported by heavy weapons. During a brief skirmish, SF and Peshmerga soldiers captured approximately thirty enemy prisoners, including several officers and two Republican Guardsmen. One Iraqi lieutenant colonel confirmed that the aerial bombardments had demoralized his soldiers, although not as much as being abandoned by their own armor and artillery units the previous day. In the end, the Iraqis on the ridge welcomed the opportunity to surrender.13