DOWNLOAD

Preparation for what would become Operation IRAQI FREEDOM began months before the start of hostilities on 19 March 2003. News that Turkey would not allow U.S. forces to pass through its territory was a surprise, but to the soldiers of the 10th Special Forces Group (SFG), it was a near disaster. Months of contingency planning had been conducted, and equipment had been painstakingly prepositioned at an Intermediate Support Base (ISB) in Turkey. The soldiers of 10th SFG would truly show their mettle by adjusting plans and executing operations in an extremely austere and flexible environment.

As with many operations, the first task of the 10th SFG staff was to get soldiers on the ground in order to show commitment. Based on their experiences in 1991 during the Gulf War, the Kurds were hesitant at first to commit to a U.S. effort to oust Saddam. A primary responsibility of Special Forces (SF) was to show the Kurdish leadership and the rank and file that the U.S. was serious and committed to combat. The only way to show U.S. resolve was to get SF soldiers on the ground and conducting combat operations with the Kurdish Peshmerga units. This meant getting as many Operational Detachments A (ODAs), the basic combat unit of the Special Forces, into northern Iraq as quickly as possible.1 To that end, an SF company (-) organized as an Advanced Operating Base (AOB) successfully infiltrated from their prepositioning location into the northern sector and made initial coordination with the Kurdish resistance organizations.2

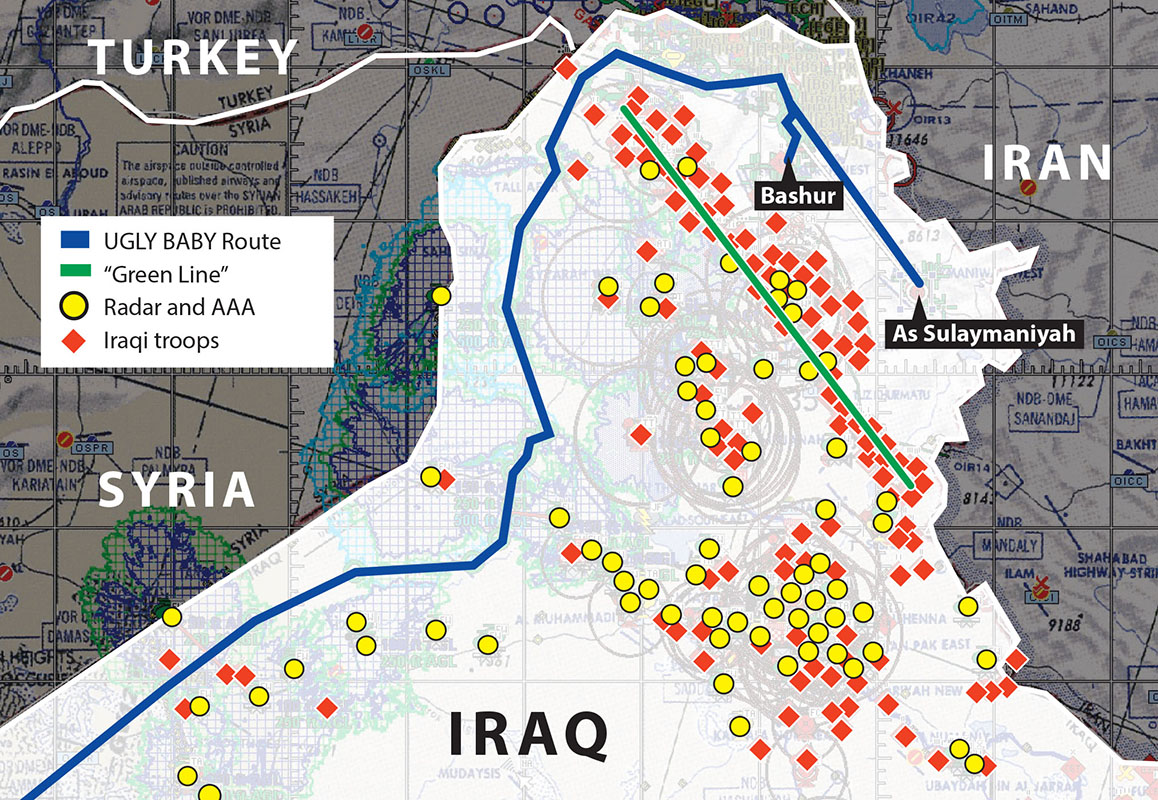

Turkey’s 1 March refusal to allow overflight to coalition aircraft prevented the rest of 10th SFG from infiltrating across the Turkey–Iraq border as planned. With driving across the border no longer an option, 10th SFG conducted air planning with the 352nd Special Operations Wing. Time was quickly running out on the carefully developed unconventional warfare plan. In the meantime, on 3 March the 10th SFG forward deployed to Constanta, Romania, in an effort to stay relatively close to the Joint Special Operations Area (JSOA). The Turkish decision to block coalition access increased the infiltration distance fourfold, from 250 miles to over 1,000 miles. For several days the State Department attempted to gain overflight permission from the Turkish government, but to no avail. As the 10th SFG staff adjusted the overall plan, logistics soldiers worked with the ODAs and aircrews to load MC-130s for infiltrations ultimately cancelled because of the overflight refusal. A bold decisive move had to be made or the U.S. would run the risk of losing Kurdish support on the northern front, freeing some of the sixteen Iraqi divisions arrayed against the Kurds for movement south to Baghdad, and possible combat against U.S. forces.3

The first leg of the bold two-day air-land infiltration was conducted by six MC-130H aircraft from the 7th Special Operations Squadron, Joint Special Operations Air Detachment–North, flying from Constanta, Romania to another staging base in theater. The second leg began at 1730 hours (Zulu time) on 22 March 2002, when three MC-130s carrying 2/10th SFG soldiers took off for Bashur Airfield, and another three MC-130s carrying 3/10th SFG soldiers, headed for As Sulaymaniyah. (Located north of Irbil, Bashur Airfield would become the site of the 173rd Airborne Brigade jump three days later.) The circuitous infiltration route covered 590 miles at altitudes under 500 feet and required the use of night vision goggles (NVGs) for nocturnal navigation. The Air Force later called this the longest low-level infiltration since World War II. The soldiers knew it as Ugly Baby.4

In planning the high-risk movement, the commanders and staff were forced to make many tough decisions. Load plans for all ODAs were altered due to weight limitations on the aircraft. Personnel were also adjusted, in case of the tragic loss of a plane, and all ODAs were task organized for split team operations.5 In the event of a catastrophic aircraft loss, the mission could continue. ODA 062 almost experienced that grim eventuality.

For most of the soldiers, the beginning of the flight into Iraq was uneventful. The commander of ODA 062, Captain (CPT) David McDougal (pseudonym), commented that during the first hour they experienced some turbulence, but it was minor enough that it felt like flying on a training mission from Fort Carson to Fort Polk. The first indication that the flight was anything but routine came when the MC-130 suddenly dropped altitude. People and equipment floated in the simulated weightlessness, the load visibly lifting and straining the ratchet straps that were supposed to keep it in place. As the plane’s descent slowed, weight returned with a vengeance, and the soldiers and payload slammed down onto the deck. The inside of the aircraft was filled with the unmistakable sound of chaff firing as the aircraft rolled and jumped to avoid antiaircraft artillery (AAA). Blinded by the darkness, CPT McDougal focused on the sound of shrapnel hitting the aircraft and anxiously “waited for the side of the plane to open up.” Then, almost as suddenly as it had dropped, the plane leveled out and flew straight to Bashur Airfield.6

The MC-130 crew performed a good landing, and the 2/10 SFG soldiers executed a combat offload, grateful to have land under their feet. As arranged, the infiltration team was met by members of their battalion and Kurdish Peshmerga fighters of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP).7 CPT McDougal and his half of ODA 062 quickly set to work training a KDP Peshmerga quick reaction force company, but found they had to do so without the rest of their team. Assistant Detachment Commander Warrant Officer 1 (WO1) Timothy Zlatich and his half of the ODA had landed in Turkey.

The “B” split of ODA 062, on aircraft number three (call sign “Harley 34”), had a much different flight experience than McDougal’s split. WO1 Zlatich remembered hearing the flashing and popping of AAA fire hitting the sides of the aircraft, and then watching as the padded insulation covering the inside of the aircraft suddenly began to shred as shrapnel cut through the skin and bounced around the interior. Once out of the heavy fire, the pilot continued evasive maneuvers and the passengers quickly checked for casualties. Miraculously, the only casualty inside the aircraft was a box of Meals, Ready to Eat. Nevertheless, the crew chief passed the word that they were diverting to Incirlik Air Base, Turkey.

Though the “pucker factor” was high for the rest of the journey, no one inside the aircraft actually knew the full extent of the damage. The MC-130 landed without problem, and as it taxied, the ramp lowered and the crew chief stepped out onto the ramp to conduct his visual checks. He quickly returned and yelled, “Run!” Responding quickly to the chief’s alarm, the soldiers conducted an emergency exit and assembled one hundred meters to the rear left of the aircraft. Only then did they see the extent of the damage—the left number one engine was blackened from fire, and fuel was gushing out of both wings. The next morning the soldiers found out that the pilot’s windshield had been blown out from shrapnel, forcing the pilot to fly using instruments alone.8 They all felt very lucky to be alive.

After landing, the SF soldiers were led by Air Force personnel to an American reception area, and stayed at Incirlik for a day. They then loaded into a C-17 on the afternoon of 24 March, and, after a quick stopover at Ramstein Air Force Base, Germany, proceeded back to their starting point—the base at Constanta, Romania. Finally, on 27 March 2003, ODA 062 “B” landed at As Sulaymaniyah Airfield and met up with 3/10th SFG (FOB 103). The forty-nine 2/10th SFG soldiers moved north by ground convoy in order to rejoin with their parent unit.9

The 2/10th SFG soldiers in the lead aircraft had an excellent view of the Iraqi air defenses that gave their brothers such trouble. To pass time on the flight, a few soldiers decided to look out the windows wearing their NVGs. Since the night was cold, they were able to easily observe the crews of a cluster of four AAA guns huddled around burn barrels for warmth. As the aircraft passed overhead, the Iraqis looked up in apparent surprise at an MC-130 passing 150 feet over their heads. They scrambled to man their guns, but were too slow to fire at the first aircraft. The trailing aircraft were not as fortunate.12 SFC Chris Yates (pseudonym), of ODA 085, was sleeping in one of those later aircraft, only to be woken by men moving around the cargo hold. He recalled, “The next thing that I know a buddy of mine on my team had his goggles [NVGs] on looking out the window. So I crawled over to look out the window, and I could see tracer fire all over the place.”13 Even as the SF soldiers observed the AAA, their pilot took evasive action and chaff soon accompanied the light show.