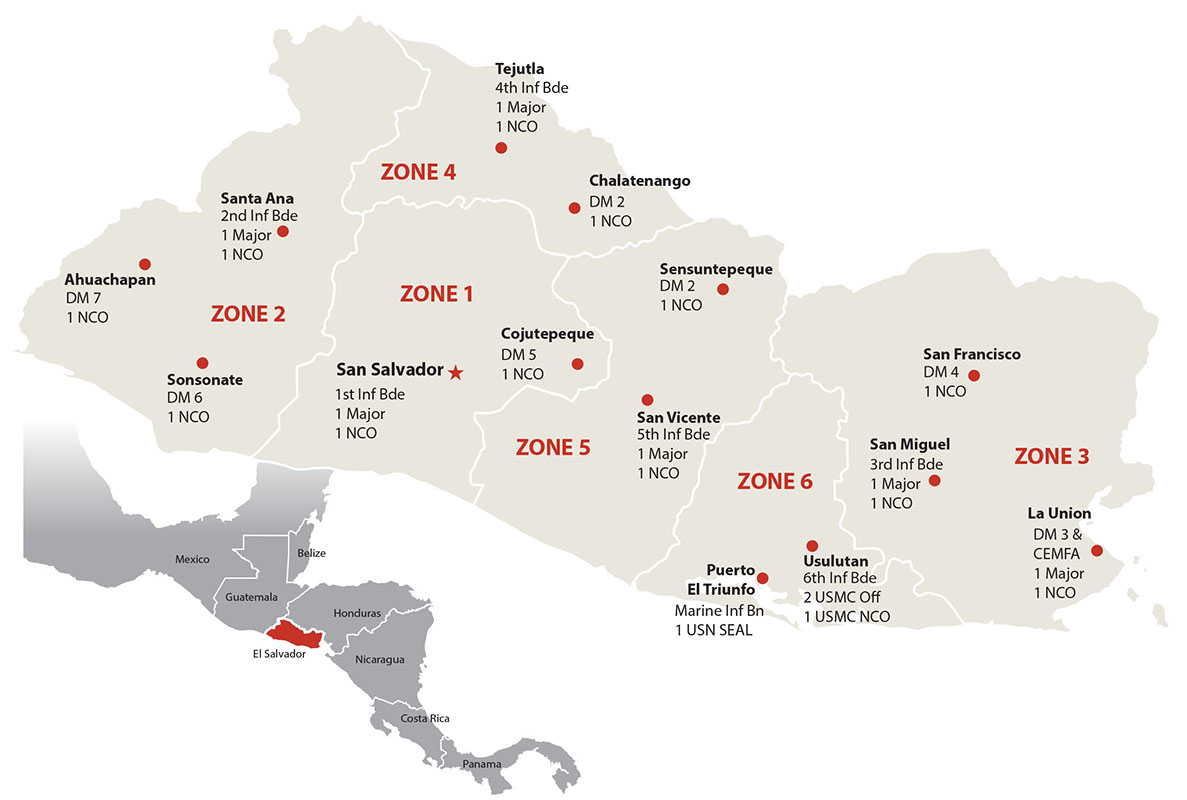

Very little has been written about the role of Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) in El Salvador during that country’s thirteen-year civil war (1980–1993). In the decade following the Vietnam War, American military intervention to prevent the spread of Communism was looked upon with disfavor, even after the Sandanistas overthrew the Somoza regime in Nicaragua in 1979. American casualties had increased dramatically during the Nixon era of “Peace with Honor” in Vietnam, and in 1973, the U.S. Congress passed the War Powers Resolution to limit the president’s authority to commit American military forces in “undeclared” wars. During the Carter administration (1977–1981), the U.S. Army leadership hunkered down and waited for better times, and counterinsurgency was regarded with disdain. These were difficult times for the executors of U.S. military assistance in Latin America: the Special Forces, Civil Affairs, and Psychological Operations elements conducting training missions, and the Operational Planning and Assistance Training Teams (OPATT) officers and noncommissioned officers assigned to El Salvador Armed Forces (ESAF) brigades as trainers.

Employing unconventional warfare tactics to counter insurgents fighting a guerrilla war is now an integral part of America’s Global War on Terrorism in Afghanistan and Iraq. Improvised explosive devices (IEDs), whether used in an urban or field environment, are standard guerrilla weapons. The majority of our combat losses in Iraq and Afghanistan are attributed to IEDs, and the same was true for the ESAF during its long war against the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Movement (FMLN) and the Ejército Nacional de Colombia (ENA). Though most of the IEDs used in Iraq and Afghanistan employ conventional military munitions, the purpose of this article is to remind ARSOF elements committed overseas today that simple field-expedient IEDs made from fertilizer chemicals, rebar rods, scrap metal, and rocks—homemade “first-generation munitions”—being employed by the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) cannot be discounted. As more conventional weapons and munitions caches are discovered and destroyed, the potential threat of encountering primitive IEDs in Afghanistan and Iraq will grow. Thus, a review of ARSOF experiences in El Salvador and similarities in Colombia is most appropriate.

The consistent commitment of 7th Special Forces Group mobile training teams to train El Salvadoran armed forces increased momentum in 1982. By then, the Salvadoran military had been fighting the FMLN for several years; however, levels of financial and material support provided to the FMLN by Cuba and Nicaragua during the Cold War were minimal compared to those being made available to insurgencies by al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups today. Thus, the majority of IEDs—artefactos explosivos improvisados—employed by the FMLN against the ESAF elements in the war were very primitive compared to those encountered in Afghanistan and Iraq today, but similar to those in Colombia. Only the term “field-expedient explosives” and effective lethality connect them.

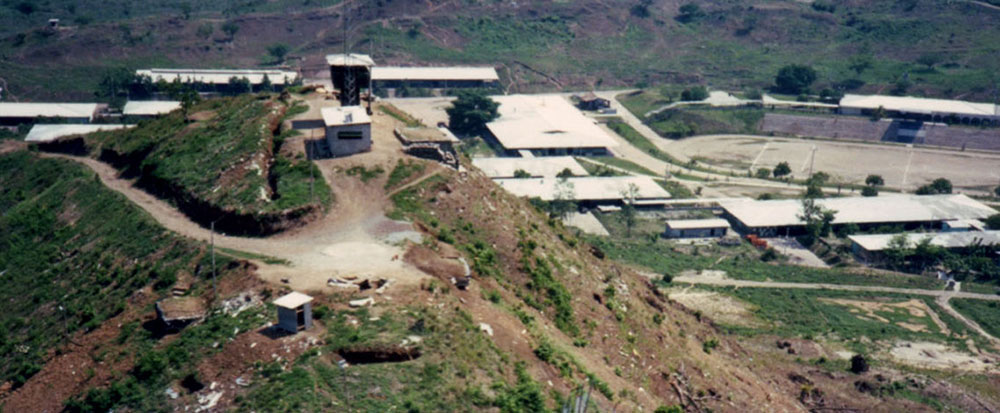

This article discusses the three most common IEDs encountered in El Paraiso and Chalatenango [Military Department 1 (DM-1, Departemiento Militar Uno)] in 1988–1989, when fighting was heaviest in El Salvador. El Paraiso and Chalatenango were the largest cities in the FMLN-dominated north. FMLN control of those two cities would split the country in half.2 El Paraiso was overrun by the insurgents in December 1983 and 31 March 1987, when Special Forces SSG Gregory A. Fronius was killed. Both times the Salvadoran military recaptured the city after fierce fighting. El Paraiso was subjected to two more major FMLN attacks in March and September 1988, and again in September and November 1989, during the last countrywide FMLN offensive. This was the “hot spot” during the Salvadoran war.

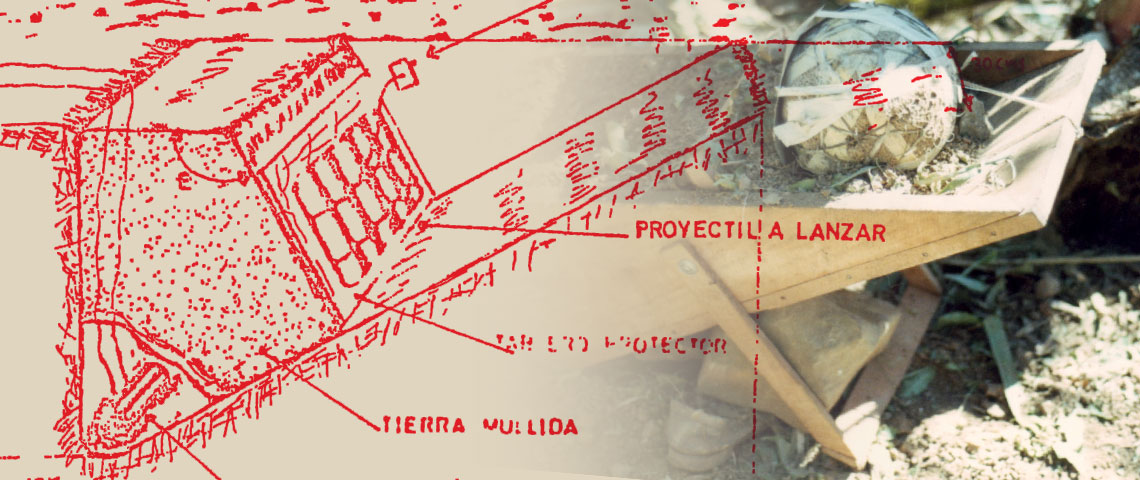

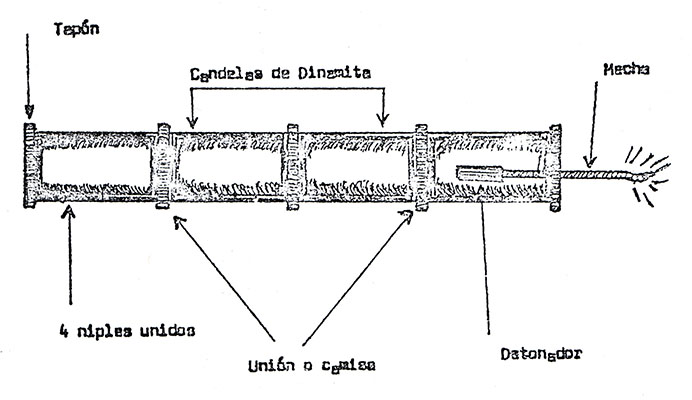

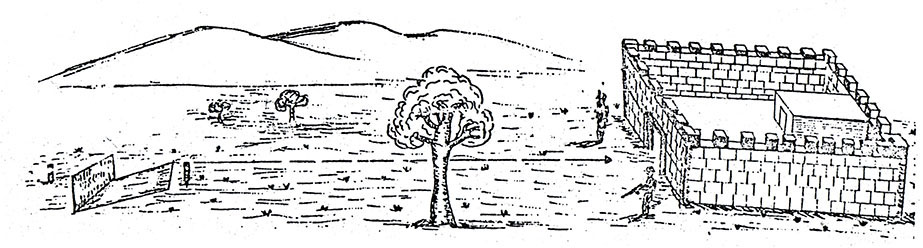

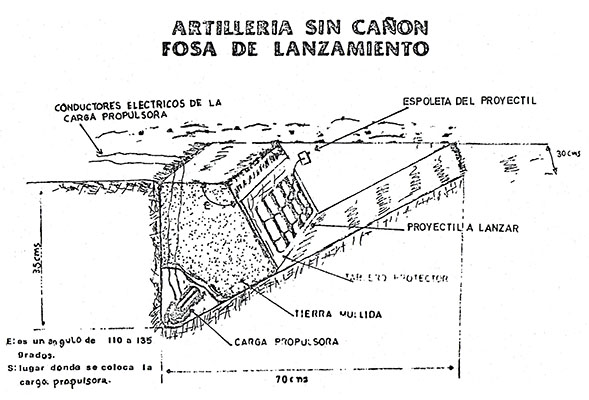

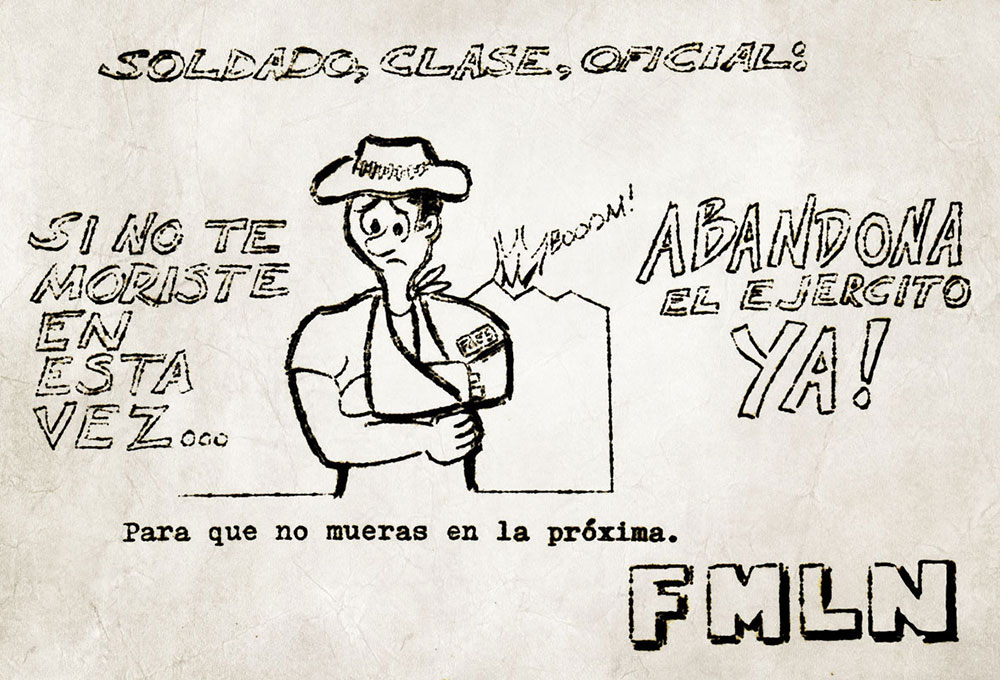

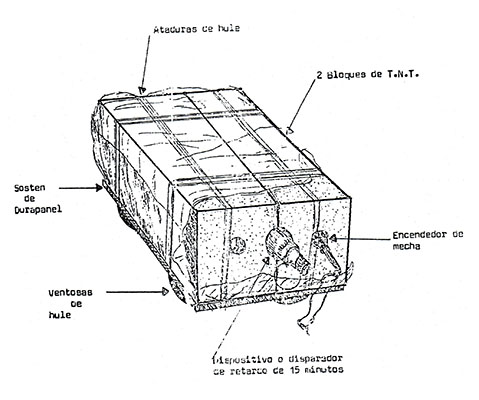

Field-expedient explosives and weapons—bloques (TNT blocks), torpedos bangalores (bangalore torpedoes), rampas (catapults), and a homemade 12.7mm rifle cañon (canon)—were used during the attacks on El Paraiso. The first two were commonly employed by the FMLN throughout the war, while the rampas appeared in 1989. The 12.7mm rifle cañon, though it might have been tested, was not fired during the 13 September 1988 attack on the 4th Brigade cuartel in El Paraiso. It was not for lack of ammunition. Bloques had been used during the numerous assaults and were left as booby-traps in ESAF fighting positions and on the .50 cal M-2 machinegun on Loma Alfa (Hilltop Alpha) when the FMLN withdrew scattering propaganda leaflets.

Bloques were simply constructed by wrapping several blocks of TNT or plastic explosive together with electrical tape or heavy rubber bands and using plastic bags to make them “water resistant”—a critical factor in daily tropical rains that also collected moisture leading to misfires. Wells were dug in the one end to accommodate detonators or fuse igniters. Detonators and fuse igniters were either taped in place or paraffin was used to secure them.3 Self-taught ESAF “bomb disposal” personnel called explosivistas would collect the abandoned bloques after the attacks to defuse and disarm them. Destruction of these bomblets was usually accomplished by the SF sergeants serving as OPATT NCOs in the ESAF brigades. They understood the danger.4

After the 13 September 1988 attack on the 4th Brigade cuartel in El Paraiso, the “inside perimeter was littered with unexploded ordnance from the destroyed ammunition supply points and bloques,” according to the U.S. Military Group (MILGP) El Salvador Flight Detachment UH-1H Huey pilots sent to evacuate the OPATT personnel.5 Bloques con ventosas de hule (bloques with rubber suction cups) were also used to destroy ESAF aircraft at Illopango Airport.6 Thus, the FMLN used bloques as large hand grenades and as satchel charges.