NOTE

*Pseudonyms have been used for all military personnel with a rank lower than lieutenant colonel.

DOWNLOAD

The post-9/11 Global War on Terrorism brought U.S. Special Operations Forces into action around the world. Among the far-flung islands of the Philippines, Army Special Operations Forces units from the 1st Special Forces Group (SFG) focused on the Islamic insurgencies in the southern islands of the archipelago, supported by the Night Stalkers of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR). Recently established on the Korean peninsula, E Company, 160th SOAR was the Army Special Operations Forces aviation element for the Pacific Command, and consequently drew the Philippines mission. The mission proved to be both tragic and triumphant for the unit.

The three MH-47E Chinook helicopters assigned the Philippines mission self-deployed from Taegu, Korea, on 22 January 2002, with aerial refuel support from the Air Force’s 351st Special Operations Wing. The eleven-hour flight was E Company’s first transoceanic self-deployment, as well as the unit’s first real-world deployment outside Korea. When one of the MH-47Es hit the refuel basket too hard and locked the probe plunger, preventing refuel, the flight diverted to Kadena Air Base in Japan for fuel. Despite the unscheduled diversion, the unit managed to stay on schedule. The second refuel, about two hundred miles from Manila, Philippines, proceeded uneventfully. Two C-17 Globemaster IIIs, carrying the unit’s equipment and support personnel, preceded the helicopters into Clark Air Base near Manila.1

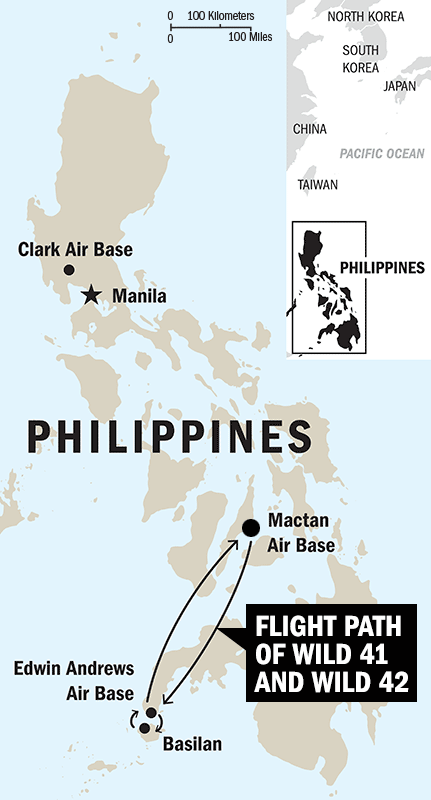

Shortly after their arrival, the MH-47E aircrews performed a Combat Search and Air Rescue mission with 1st SFG personnel. They then supported B Company, 1st Battalion, 1st SFG, at Fort Magsaysay, where the company was training with the Philippine Army’s Light Reaction Company as part of Joint Combined Exercise Balanced Piston 01. Following this training, the MH-47Es relocated roughly four hundred miles south to Mactan Air Base, on the island of Cebu. During this period, air missions gradually shifted from daylight to sunset departures in preparation for the night flights necessary to support Exercise Balikatan (meaning shoulder-to-shoulder in Tagalog), which was a major component of the Cobra Gold exercise series. They staged out of Edwin Andrews Air Base (EAAB) at Zamboanga, on the southern island of Mindanao. The 350-mile round-trip flight from Mactan Air Base to EAAB took over six hours and required aerial refueling en route. The focus of E company’s mission was to give aviation support to the Special Forces (SF) elements on Basilan Island, south of Mindanao.2

With the advanced elements already in place, the remainder of the 1st SFG Advanced Operating Base and Operational Detachment-A (ODA) personnel began deploying to Basilan on 17 February 2002. Having flown from Okinawa, Japan, on blacked-out MC-130s and arriving in Zamboanga at night, many of the ODAs were expecting to conduct an unconventional warfare mission with the normal accompanying security measures. Thus, it was quite a surprise to the soldiers when the first sortie of MH-47Es landed on the floodlit Camp Tabiawan landing zone northeast of the Basilan capital of Isabela, and a contingent of the local press was on hand waiting to take pictures. Media scrutiny of the event was intense and the teams made every effort to escape the spotlight. But before all the ODAs had time to get out to their respective Philippine Army units from Isabela, disaster struck the Night Stalkers.3

On the night of 21 February 2002, E Company’s mission required them to insert the last group of ODAs onto Basilan as well as deliver supplies to the Special Forces elements already in place. The two MH-47Es, code named Wild 41 and Wild 42, formed the two-ship mission from Mactan to Zamboanga, and flew their programmed route to the objectives at 150 feet above the water. Two MC-130P Combat Shadow refueling aircraft from the 351st Special Operations Wing accompanied the Chinooks and orbited in separate aerial refuel tracks—one on the east side and the other on the west side of Basilan Island—in the event the helicopters needed additional fuel after completing their insertions and supply runs. At the last minute, the late addition of a VIP contingent to accompany the insertion changed the load configurations of the two helicopters.4