The 3rd ID had no PSYOP plan. The Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance and the subsequent Coalition Provisional Authority had no PSYOP plan, and the Central Command Joint Psychological Operations Task Force forward in Qatar, had redeployed to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Major Donald Thomas*, the 315th TPC commander explained, “There was no plan to fall in on. There was nothing from higher coming down. You would get these short suspenses to execute on a topic. That is not a campaign plan. There was no synchronization matrix that said ‘Here is our plan for the next three months, and here is what you need to start developing.’ Every PSYOP company was essentially running its own PSYOP campaign plan.” Although each division coordinated PSYOP plans internally there was no opportunity for external coordination.

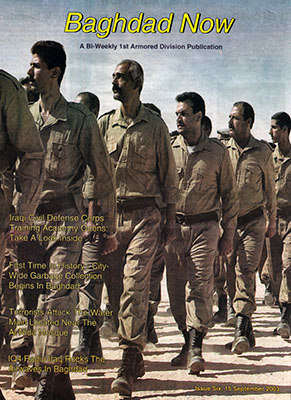

Each tactical PSYOP detachment commander had to establish a relationship with his assigned brigade. In the beginning, the 3rd ID and 1st Armored Division expectations outstripped the capabilities of the detachments. Captain Ron Castle*, commander of Tactical PSYOP Detachment 1210, explained, “When we first got [to Baghdad], these maneuver guys were demanding a real quick turnaround, [but] we weren’t able to supply that.” The combat brigades and battalions responded by designing and distributing their own Information Operations products. Then, the tactical PSYOP detachments had to convince the commanders to use the PSYOP products instead of their Information Operations products. The detachments tried to anticipate brigade commanders’ needs and to develop products accordingly.

Maneuver commanders focused on troop safety. They did not initially understand nor appreciate the long-term goals of PSYOP. The commanders wanted products that would enhance security now instead of products that would lead to long-lasting changes in Iraqi culture or behavior. Thomas summarized the issue:

When you have maneuver guys that are not PSYOP trained, they tend to have a short-term view. It’s fine to address an immediate need, but it doesn’t address the psychological, long-term goal that you are trying to achieve. We were constantly battling with maneuver commanders, saying, ‘I know that our soldiers are getting killed, and that is something that is very important to you. But, you know what, the target audience doesn’t care about our soldiers much. We need to address topics that are important to them on a long-term basis, because we are trying to change the culture of the country.’ We constantly battled this. What they would want was a short-term product. All they cared about was a handbill that talks about rockets, a handbill that talks about IEDs [improvised explosive devices]. And that is not PSYOP.

Captain Marvin Holiday*, commander of TPD 1220, agreed: “At least for us, that was one of the hardest parts about [product] dissemination. Some of the products being generated or pushed by the maneuver commander appeared to be self-serving. ‘We’re going to focus on IEDs. Well, only Americans are getting killed by IEDs. The Americans only want IEDs to stop because they are killing Americans. You’re not helping Iraqis. Tell us how you are going to help us, and maybe we’ll report this information.’” The 315th TPC tried to balance products that addressed the commanders’ short-term concerns with products that addressed long-term PSYOP goals, such as those emphasizing progress in rebuilding a better Iraq.

At times the PSYOP teams had to show the maneuver commanders that in psychological operations, often no news was good news. Captain Chambers* described the maneuver soldiers’ attitudes: “The infantry officer or the armor officer is used to putting steel on a target and seeing an immediate effect. ‘I fired my weapon and I killed something.’ The long-term, residual effect of a PSYOP product is going to be delayed. You may never see a reaction to a product you’ve disseminated in the area.” But the cumulative effects of the PSYOP messages become evident over time. It was difficult for maneuver commanders to understand that PSYOP effectiveness can often be calculated in terms of negative activity. Thomas recounted, “What we’d have to do is get into these Socratic philosophical discussions. [The commanders would say], ‘We want to know what you guys are doing.’ ‘Well, here’s what we’re doing: Are you seeing mass demonstrations?’ ‘Well, no.’ ‘Are you seeing negative attitudes towards Coalition forces?’ ‘Well, no.’ ‘That’s where PSYOP comes in.’”

Once the brigade combat teams understood the capabilities of the tactical PSYOP teams, the units worked effectively together. TPT 1214 worked with the 1st Platoon, Hawk Troop, 1st Cavalry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, from 10–31 May. Hawk Troop controlled the distribution of scarce propane gas. When Hawk Troop began its mission, Iraqi civilians would riot at the distribution stations, sometimes in groups of more than three hundred. On five occasions, the riots grew so large that TPT 1214 had to shut down the loudspeakers and help the Hawk Troop soldiers employ riot control measures. However, the PSYOP team’s primary weapon against the rioters was its loudspeakers. By daily broadcasting messages explaining the propane distribution system and encouraging cooperation, the team reduced the number and severity of the riots.

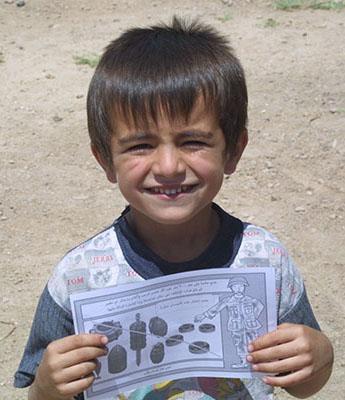

One of the 315th’s early missions was to disseminate safety information to the residents of Baghdad. The city’s usual modes of communication—radio, television, and telephone—were so badly disrupted that the U.S. Army had to rely on old-fashioned means to spread its message: paper. One part of the safety campaign involved educating the public about the presence and danger of unexploded ordnance and munitions throughout the city. The product development detachment designed and produced two-sided leaflets with pictures of different ordnance and instructions on how to report mines and weapons caches. The TPTs then distributed the leaflets by hand to the public taking the opportunity to interact with Iraqis on the street. Sergeant Reed Costner* summarized: “Our mission is basically encouraging mine and unexploded ordnance awareness through leaflets, posters, and face-to-face communication.”

Another PSYOP campaign was against electrical wire theft. “No sooner would they put up new wire than it would be gone the next day.” Thomas described the thrust of the PSYOP effort:

We had to constantly try to correlate the actions of the individual to the greater good. People were more focused on gaining whatever money they could by stealing and reselling electrical wire and had no interest in the bigger problem. When the locals were confronted with the situation there responses was: ‘Oh, if I steal from my neighborhood, we won’t have power. You’re absolutely right.’ If they did understand the implication, they would simply go steal from another neighborhood, not caring that they were causing problems for the entire city.

One detachment commander encountered a woman who simply did not care about anybody else:

This lady told me straight up that she didn’t care about anybody that did not live in her little neighborhood which had a Baath Party headquarters. They used to get electricity twenty-four hours a day. So, when they started to push [electricity] out to everyone, causing temporary blackouts, she told me, ‘I don’t care. If that’s the way it is, then the Americans need to go out and buy generators for everyone in this apartment building. Unless we get that, I’m not going to be happy.’

Frustrating as it was, by the end of the PSYOP campaign, looting of wire had been considerably reduced.

Psychological operations in Baghdad were not all paper and handshakes. More than one tactical PSYOP team encountered violence, and all five of the 315th tactical PSYOP detachments participated in cordon and search operations and raids. While raids were usually conducted in conjunction with conventional forces, on one occasion the PSYOP soldiers acted alone. On 27 April, TPD 1280 surrounded a residence and broadcast a surrender appeal to the six men inside, who were systematically robbing the house while waiting for the owner—a former member of the Baath Party—to return home so they could murder him. All six heavily armed men surrendered without a fight. While two soldiers guarded the criminals, two PSYOP soldiers cleared the house. TPD 1280 confiscated the thugs’ stolen pickup truck, several grenades, an RPK machine gun, six AK-47s, six pistols, and ammunition.

Earlier in May, teams from TPD 1230 had converged to help prevent a riot around Abu Hanifa Mosque in the Aadhamiyah District of northwest Baghdad. Using their loudspeakers to call for peaceful behavior, distributing leaflets with similar messages, and simply engaging demonstrators in conversation, the PSYOP teams helped prevent a potentially violent confrontation between insurgents, civilians, and Coalition troops. The scenario was repeated often in the days and weeks following the fall of Baghdad. The TPT response to riot situations was to broadcast appeals for nonviolence, identify key personalities in the crowds, and address the people’s grievances as best it could.

One TPT had the opportunity to use its PSYOP equipment in its defense. A TPT 1213 vehicle was hit by an IED while distributing handbills in Al Hara, Baghdad. The vehicle was damaged by the explosion, but not completely disabled. The team quickly grabbed its most effective weapon—the loudspeaker—to defend themselves. As soon as they started broadcasting, several Iraqis came forward and told them about two more IEDs along the convoy route. With this information, TPT 1213 was able to safely route help to them.

The vast majority of the 315th TPC products were designed internally. Thomas said: “Our guys, who had never done this before, designed [almost] every product that we put out.” Since the Joint PSYOP Task Force forward at Qatar, the endpoint for the much-touted “reach-back system” of the 4th PSYOP Group, had redeployed to Fort Bragg, the Army Reserve PSYOP units in Iraq were on their own. Using photo editing and design software, the soldiers of the product development detachment translated ideas from the field into realities that were quickly sent back for distribution. As TPTs and TPDs saw needs and obtained feedback from civilians, they sent them back to the product development team. Situation reports from the TPTs were often very clear: “Stop using this product, because it’s just pissing them off!” Once turned into a viable PSYOP design, the product was given to a locally contracted printer. They were able to produce four-color handbills or posters on demand, which cut product turnaround to a matter of days.

Circumstances—no printing equipment—caused the 315th to resort to contracting local printers. While the mission was to distribute hundreds of thousands of PSYOP handbills, it had no capability to produce them. Major Chip West*, chief of the product development detachment, explained how the company solved the problem:

One of the teams came back and said ‘Hey, we met this printer.’ Because I had contracting experience, I went and found the division contracting officer. We discussed [the requirement] and established a Blanket Purchasing Agreement rather than a service contract. The 1st Armored Division started dumping money into it; … fortunately, the G-8 [comptroller] was a former Special Forces guy who understood special operations. He said, ‘This is all the information that I need.’ In order to have competition, I found another three printers. There are four printing contracts that run through the BPA.” The purchasing agreement meant that the 315th did not have to bid each print job; rather, it simply placed orders with the contracted printers and received good, timely service. Thomas added, “In an emergency, we could [produce] 200,000 handbills, double-sided, four-color, in roughly twenty-four to forty-eight hours.” Access to four local printers enabled the 315th to design and distribute about 1.2 million handbills and posters a week if necessary.