DOWNLOAD

During the Korean War, special operations were conducted by all American military services, United Nations (UN) forces, Korean civilian and military elements, and a fledging Central Intelligence Agency. In addition to being surprised by the North Korean invasion of South Korea in June 1950, neither General Douglas MacArthur, his Far East Command (FEC), nor the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had developed strategic, operational, or tactical special operations contingency plans for Korea. Roles in behind-the-lines operations had not been defined.1 The only special operations asset available in the Pacific was a B-29 Superfortress “carpetbagger” (Psywar leaflet) squadron based in the Philippines.

General MacArthur had “stonewalled” any civilian agency that sought to conduct military or paramilitary operations in his theater of war. During World War II, he kept the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) out of the Southwest Pacific, although it performed quite well in Europe, the Mediterranean, Burma, and China. MacArthur did not want the OSS successor setting up shop in Korea, even though the Agency had been running agents into Communist China and North Korea since the end of WWII and had accrued a substantial amount of regional knowledge.2

With the exception of the small 971st Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment in Seoul, the FEC commander in Japan had no covert intelligence collection capability in Korea. Despite 971st reports of North Korean divisions in the Lee Hong-won Branch of the Chinese 8th Route Army in Manchuria before the war, Major General Charles Willoughby, the FEC G-2 (security), chose to ignore the implications.3 Shortly before the North Koreans invaded South Korea and drove the Americans and Koreans into a final defensive perimeter around Pusan, General MacArthur reluctantly agreed to allow the CIA to establish a small office in Japan. It was fortuitous that Colonel Richard G. Stilwell, detailed from the Army, was serving as the Director of Far East Operations. The Agency became an independent player, not only because MacArthur disliked and distrusted anything he could not control, but also because of its unique global strategic mission. The FEC had a regional view and focused on the strategic implications of Korean events.4

Still, when North Korea invaded in June 1950, the new agency had done little to define its role in behind-the-lines operations anywhere.5 It was not until the Red Chinese intervention shattered UN Command illusions of a quick victory that U.S. military planners began to seriously consider guerrilla operations. Guerrilla operations could relieve some pressure on frontline UN units by destabilizing enemy rear areas.6 And they were an inexpensive force multiplier for the Eighth Army.7

Though peace talks in the summer of 1951 served to halt the UN advance on or near the 38th parallel, there was no cease-fire. No longer distracted by intelligence crises of the moment because the main line of resistance was somewhat stabilized, all military intelligence elements and the CIA began to expand covert operations and to build a support structure to deal with a new form of warfare. It became a wider secret war because it was the only combat arena in which efforts could be intensified. It was waged widely, but with minimal coordination.8 On the seas surrounding Korea, the U.S. Navy and Marines, British Commandos, and the CIA raided coastal targets, seized military personnel, and destroyed rail and road infrastructure. Submarine and surface ships carried Marine Force Reconnaissance Teams, Underwater Demolition Teams, British Commandos, Army-advised partisans, and CIA guerrilla raiders.9

The purpose of this article is four-fold: first, to remind our readers that USASOC has an “Army Special Operations Forces in Korea, 1950–1953” history in progress; second, to separate the CIA covert maritime operations from military special operations activities during the Korean War; third, to reveal the critical role U.S. Army sergeants had in special operations while detailed to the CIA; and lastly, to capitalize on recent primary research—veteran interviews. This article uses an Army paratrooper who conducted paramilitary operations with JACK (Joint Activities Commission, Korea) during the Korean War—former Sergeant First Class Thomas G. Fosmire—to explain some maritime missions from his perspective as an operative. JACK was the CIA cover for status in Korea.

With the dissolution of the OSS after World War II, most U.S. military operatives returned to their parent services or civilian life. Thus JACK, like the Ranger Airborne Infantry companies formed for combat in Korea and Special Forces in 1952, recruited veterans from the OSS and SOE (Special Operations Executive), Rangers, Marauders, paratroopers, Para-Marines and Raiders, and Navy Underwater Demolition Team personnel for “details” with the Agency. An “old boy” network of former connections was used to identify military personnel for JACK.10 With Colonel William DePuy, Colonel William Peers (OSS Detachment 101–Burma), and Colonel Stilwell detailed to the CIA, Major John K. “Jack” Singlaub (OSS Europe and Indochina) was selected to be the military deputy of JACK in Korea. That modus operandi of recruiting was popular … much to the chagrin of some WWII parachute infantry officers trying to serve with the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team.11

Numerous U.S. military (all Defense services) officers and sergeants “served” in JACK, yet few knew about all activities due to compartmentalization by a “need to know.” JACK paramilitary operations were conducted simultaneously while the U.S. military services, the UN, and the South Koreans ran special operations activities. The limited naval and air assets in and around Korea had to support everyone. Thus, special operations conducted during the Korean War have been regularly intertwined by military analysts to promote the existence of a grand special operations strategy by simply joining together the most enterprising and successful tactical operations achieved by several commands and a variety of elements. To compound the grand strategy illusion, General Matthew Ridgway, who succeeded MacArthur in 1951, directed that a new Army-controlled command be formed to oversee and coordinate all covert operations in theater. This was the Combined Command for Reconnaissance Activities, Korea (CCRAK).12

CCRAK was to coordinate all special operations in Korea. Every Army, Navy, Marine, Air Force, and allied unit; South Korean military and intelligence elements; and the CIA doing behind-the-lines operations were to be represented in the command. However, CCRAK was a coordinating headquarters; it had no command authority. FEC appointed the commander while the Document Research Division (CIA liaison office) provided the deputy director. Army Major Singlaub, the deputy JACK commander and deputy station chief for Korea, also filled that position. The CIA reported directly to Washington. Its worldwide strategic mission transcended that of Far East Command. In his memoirs Singlaub simply stated “that JACK had neither the responsibility nor inclination to coordinate its independent covert activities with CCRAK.”13

CCRAK had no explicit command authority over JACK. It expected JACK to coordinate but JACK was not required to do so.14 Though CCRAK was really a “paper command,” Singlaub considered it as a rival for personnel, funding, air support, and above all, mission authorization.15 Scarce air and naval resources would be allocated based on availability, not mission need.16 Need was CCRAK’s source of power. However, the greatest flaw was that covert activities in FEC had been relegated to a staff rather than a command function.17

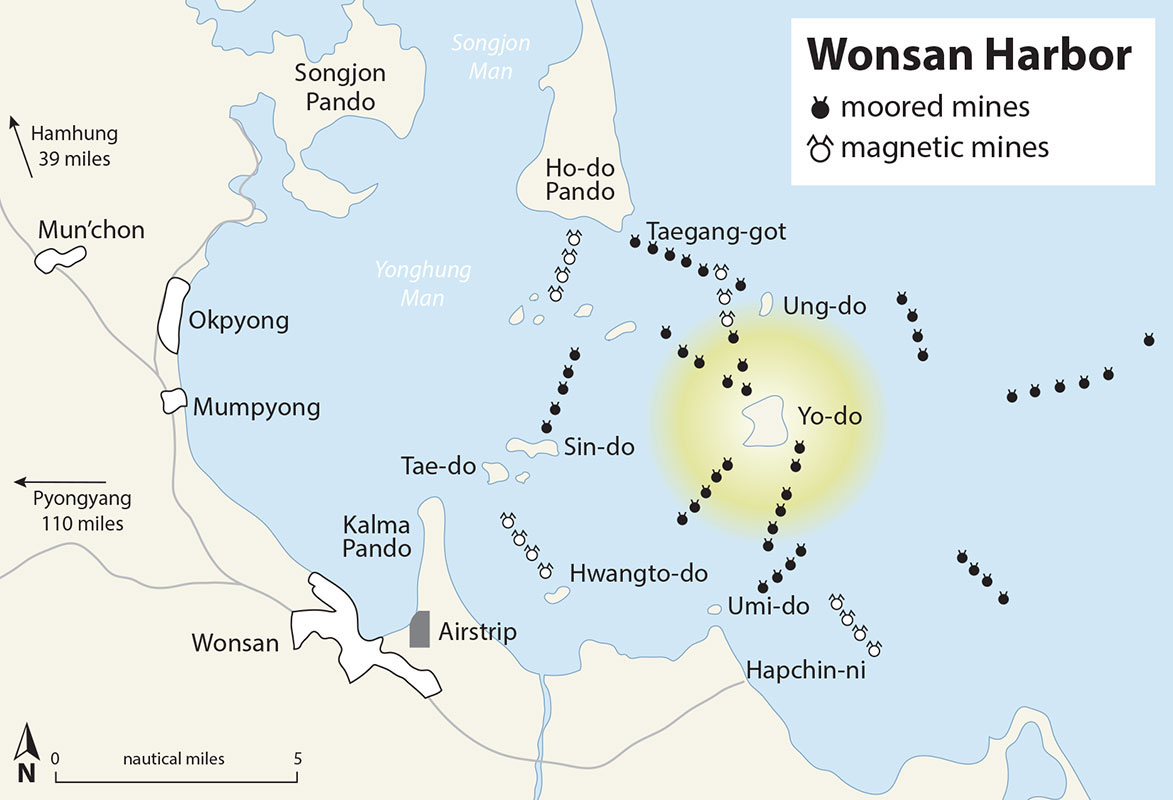

Typical of special operations today, the military and civilian working relationships at the tactical level were marked by a very distinct cooperative attitude among case officers and field operatives.18 JACK special operatives in the maritime branch overcame dysfunctional command, control, and coordination to become quite successful during the Korean War. Some JACK maritime operations conducted from Wonsan to the Tumen River (northeast border with China) from 1952 through 1953 will be explained by a veteran.

Former Sergeant First Class Thomas George Fosmire from Wisconsin joined the Army as an airborne enlistee on 31 August 1948 to “catch up” with his older brother. Chuck Fosmire, a draftee, had fought with the 9th Infantry Division in Europe during WWII. After the war he reenlisted for Airborne School and was subsequently assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division. During the winter of 1948–1949, Private Tom Fosmire received basic infantry training with the 7th Infantry Regiment (Cottonbalers) at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, before leaving for jump school at Fort Benning, Georgia. In 1949, glider qualification was accomplished during the first week. Three weeks of parachute training followed.

It was June 1949 when Corporal Fosmire joined D Company, 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, as a 81mm mortar man. By then, his brother Chuck was serving in the 82nd Airborne Division Reconnaissance Company. A year later, after some finagling by both, Tom joined his brother in the 82nd Reconnaissance Company. When war broke out in Korea in June 1950, Tom hoped that the two could fight together. After several months on alert, it became apparent that the All-American division was not Korea-bound. The newly-promoted Sergeant (SGT) Tom Fosmire volunteered for the Rangers, but like many others, his first sergeant would not release him.19

Totally frustrated in his efforts to get into the war by the fall of 1951, and with Chuck gone to become a warrant officer in counter-intelligence, Tom re-enlisted for Korea. He was determined to earn his Combat Infantryman Badge as his brother had in WWII. Military service was a family tradition. His father had been gassed and wounded while fighting as an infantryman in the 32nd Division in France during WWI, and wore the German bullet as a tie clasp.20 Re-enlisting for Korea was the only way to get into the war.

While aboard the USTS Marine Adder traveling from Seattle, Washington, to Sasebo, Japan, SGT Fosmire never imagined that his Combat Infantryman Badge dream would go unfulfilled. When he got to the replacement depot (“Repo” Depot) at Camp Drake, Japan, virtually all combat arms soldiers were being processed and shipped to Korea in less than forty-eight hours. Casualties had been very heavy during the winter of 1951–1952. When he reached the head of the in-processing line, Fosmire was more than ready to “grab his gear” and get on the bus to the airfield.21

Instead, he was told to report for an interview in an office of the Far East Air Forces Technical Analysis Group (FEAF/TAG) in downtown Tokyo. When Fosmire objected to this diversion from combat, the replacement company commander advised, “You ought to take the assignment, but you can come back. Then, you will definitely go to Korea as an infantryman.”22 Curiosity more than anything prompted him to get on the troop bus to Tokyo.