SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

June 1944 was a watershed month for the Allies in World War II. The 6 June 1944 D-Day landing in Normandy to spearhead the assault on Fortress Europe has received the lion’s share of attention by military historians overshadowing the seizure of Rome, Italy, on 4 June 1944. The Allied offensive, Operation DIADEM, which covered the breakout from Anzio and a general attack along the southern Italian front in May 1944, ended an eight-month stalemate of bitter fighting in the Italian mountains, south of Rome. Suddenly, the German lines broke and the race for the Italian capital was on. In Lieutenant General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army it seemed as if every unit commander from corps down to company level and platoon leaders wanted to be the first into Rome.1

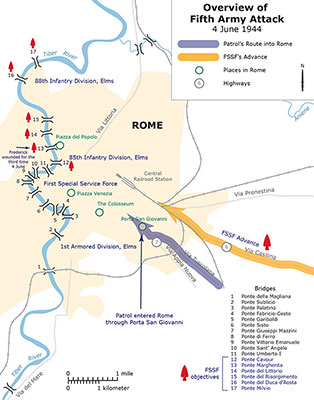

Leading part of the assault into Rome from the Anzio beachhead was the U.S.-Canadian First Special Service Force (FSSF). The Fifth Army effort included two corps consisting of six infantry and one armored division, all with the goal to capture the capital city.2 However, the distinction of being the first unit into Rome goes to a special patrol composed of handpicked soldiers led by an officer from the First Special Service Force, Captain T. Mark Radcliffe (see sidebar).3

Given only four hours to clear Fort Benning, Georgia, T. Mark Radcliffe joined the FSSF as one of its first officers (a second lieutenant) at Fort William Henry Harrison, near Helena, Montana, on 18 July 1942.4 Outstanding performance in the Aleutian campaign and in Italy caused him to be selected to command 3rd Company, 3rd Regiment. After bitter fighting in Italy, which included daring mountain assaults on Monte La Difensa, Majo, and La Remetana, the casualty-ridden FSSF was thrown into the Anzio defense on 1 February 1944. Despite having a strength of only 1,300 combat troops (down from the original 2,300), the Force was to defend a thirteen-kilometer front, one-fourth of the Anzio perimeter. To put this in perspective, the 10,000 man 3rd Infantry Division had a seven-kilometer front).5

On 14 March 1944, while leading a five-man reconnaissance patrol in front of the FSSF sector, Radcliffe was captured. Bound and gagged, the Germans took him to Littoria for interrogation. After being hit on the left side of his throat with a rubber club, Radcliffe escaped and made his way back to the Anzio perimeter. A patrol from his own company found him and brought him back through the lines. (See “Prisoner for a Day: A First Special Service Force Soldier’s Short-lived POW Experience”.) Wounded while evading, Radcliffe was initially taken to the regimental aid station. Field hospital doctors on the Anzio beach felt that the shrapnel wounds in his foot and left leg were beyond their expertise and shipped him to the 36th Combat Hospital near Naples. Radcliffe had been recuperating for almost a month after a successful operation to his foot, when he heard that recovered wounded soldiers were being sent to the replacement depot for reassignment. Most did not return to their original units.6

For those soldiers assigned to elite units like the FSSF and the Ranger battalions, being reassigned to another unit was considered a “slap in the face” rejection. The veteran would lose the camaraderie and friendship developed in training, hardened in the Aleutians, and proven during the Southern Italy campaign. Rather then run the risk of being reassigned elsewhere, Captain Radcliffe sneaked away from the hospital to rejoin his unit. This proved to be his second escape and evasion in less than a month, albeit this time from the Americans. However, once in the city of Naples, getting to Anzio posed a problem: he had no access to official transportation. By chance, Radcliffe ran into a friend from Salt Lake City, Utah, in Naples. This friend was a Piper Cub liaison/spotter plane (probably an L-4 aircraft) pilot that flew into the Anzio beachhead as part of a courier service.7 Every flight was dangerous because German artillery fire bracketed the beachhead. Small planes could only land and take off at dawn and dusk. Radcliffe convinced his friend to take him along, but fearful of a courts martial for carrying an unauthorized passenger, they effected a plan. Once the plane landed and turned to taxi to the parking area, Radcliffe was to roll out of the plane in the dust cloud thrown up by the engine. He then simply walked to the road and hitched a ride to the 3rd Regiment headquarters. Shortly after being greeted by Colonel Edwin Walker, Radcliffe was summoned to the First Special Service Force headquarters.8

Brigadier General Robert Frederick rewarded Radcliffe by assigning him a special mission. “Welcome back!” he said, “I’m sorry, but I can’t send you back to your company, there is too much at stake. We are going to be pushing off at this place in about two days. I figured that I would put you on a special mission. Report to General Keyes, the II Corps commander, at his headquarters.”9

The II Corps special mission was to lead an advance patrol into Rome. The force consisted of sixty handpicked men from II Corps units, including three from the FSSF. They were to “… in any way possible get into Rome ahead of other Allied forces, send back the enemy situation within the City, and at the same time post II Corps route signs along prominent streets and in public squares.”10 Mounted in eighteen jeeps and two M-8 armored cars, the advance force would rush ahead into Rome for the liberation. The ad hoc assault force needed little training because all were combat veterans; each had been handpicked for his outstanding performances in combat and his personal courage.11 The three FSSF soldiers selected for the assault force were Sergeant Thomas W. Philips (Seguin, Texas, assigned to 1st Regiment), Staff Sergeant K.R.S. Mieklejohn (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, assigned to 2nd Regiment), and Sergeant J.E. Brannon (Princeton, New Jersey, from 3rd Regiment). To document this success at being first into Rome the force had “…one movie camera man, two still camera men, and a news reporter, attached for media coverage.”12

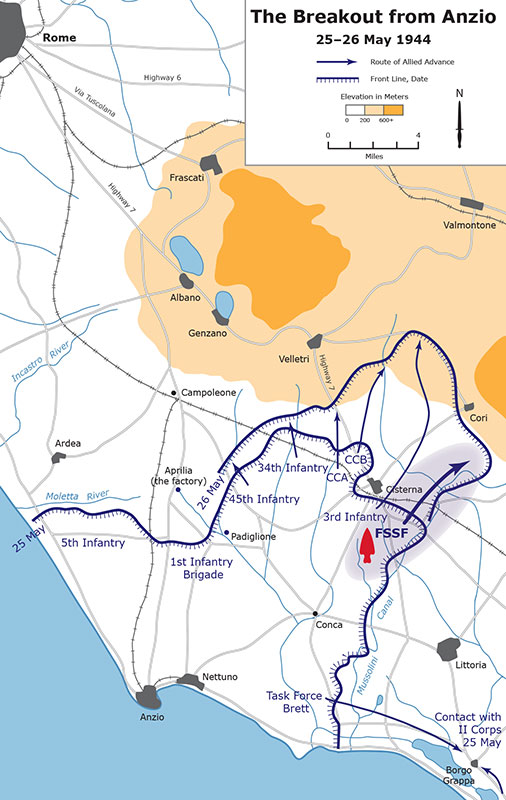

Operation BUFFALO, the initial breakout from the Anzio beachhead, was preceded by a tremendous artillery barrage and naval gunfire at 0545 on 23 May.13 In the breakout, the FSSF mission was to screen the right flank of VI Corps as it moved north toward Valmontone and Highway 7. To accomplish the screening mission, the FSSF had several heavy units: the 645th Tank Destroyer Battalion (-) and two companies of M-4 Sherman tanks from the 191st Tank Battalion were attached.14 The 463rd Parachute Field Artillery Battalion’s 75mm howitzers provided direct-fire support.15 As the FSSF moved northward, the Japanese-American 100th Battalion screened its far right flank.16 Ten days after the breakout, the FSSF was transferred from VI Corps to II Corps for the final push to Rome. When the reinforced FSSF began its final attack toward Rome, CPT Radcliffe was preparing his force for its mission.

“To make up for combat losses the FSSF was assigned about 400 Rangers following the dissolution of the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Battalions after the Cisterna debacle. The Ranger replacements brought the FSSF up to about 2,000 soldiers (bringing the unit to about 86 percent strength). Equally important, the Ranger Cannon Company (four M-3 half-tracks mounting 75mm cannon) was transferred to the FSSF headquarters bringing much needed firepower”17

Even though he had a force of experienced veteran soldiers, CPT Radcliffe took time to plan and rehearse actions since none of the soldiers had worked together. His primary concern was immediate reaction to German ambushes and roadblocks. In case of enemy contact he wanted to make sure that the force reacted as a whole, not sixty individual soldiers. Their main strategy was to eliminate or bypass the enemy as quickly as possible and continue to race for Rome. If the enemy were too strong they would call for armor and bypass the obstacle letting the heavier armed units take care of the problem.18

The advance patrol departed II Corps headquarters at 1400 on 3 June 1944. Tucked into CPT Radcliffe’s pocket was a pass issued by Major General Geoffrey Keyes giving his element top priority on all roads in the II Corps sector. As he prepared to leave the headquarters area, CPT Radcliffe was handed some signs that read “Follow the Blue to Speedy Two!” The signs had two purposes: first, to guide II Corps units to Rome; second, perhaps more importantly, they were designed to needle the VI Corps commander, Major General Lucian Truscott, whose forces were also racing toward the Italian capital.19

Part of Radcliffe’s mission was to link up with an armored column, Task Force Howze, under the command of Colonel Hamilton Howze, who was to spearhead the II Corps drive to Rome.20 The combined arms task force composed of M-4 Sherman tanks, tank destroyers, and armored infantry would protect the lightly armed advance patrol enabling Radcliffe to dash into Rome.21 When Radcliffe’s group reached Frascati, he was told by the 2nd Battalion, 338th Infantry (85th Infantry Division), that an armored task force had already passed by an hour earlier. “So much for a coordinated effort,” thought Radcliffe. In the rush to catch up with Task Force Howze his group passed an unidentified armored column, seemingly stalled on the side of the road. As they went by, CPT Radcliffe noticed a perplexed look on the lead tank commander’s face.22