DOWNLOAD

The first operational test of the Army’s Special Operations aviation capability came in Operation URGENT FURY, the 1983 rescue of American students on the Caribbean island of Grenada. Formed in the aftermath of the failed 1980 Iranian hostage rescue, Task Force 160 was the result of the Army’s quest to build an aviation unit specifically designed to support special operations. The 101st Airborne Division provided the elements that composed the organization. Originally called Task Force 158 when formed in 1981, the unit was later designated by the Army as the 160th Aviation Battalion and eventually grew to become the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, the Night Stalkers.1

Companies C and D of the 158th Aviation Battalion of the 101st Aviation Brigade provided the Army’s newest helicopters, the UH-60 Black Hawk. OH-6A Cayuse (referred to as Little Birds in the 160th) came from the 229th Attack Helicopter Battalion and medium lift CH-47 Chinooks came from the 159th Assault Support Helicopter Battalion. All units were headquartered at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.2 Events in the Caribbean initiated the first combat test of TF 160. In less than ninety-six hours, the Task Force would alert, deploy, and conduct combat operations in a hostile environment.

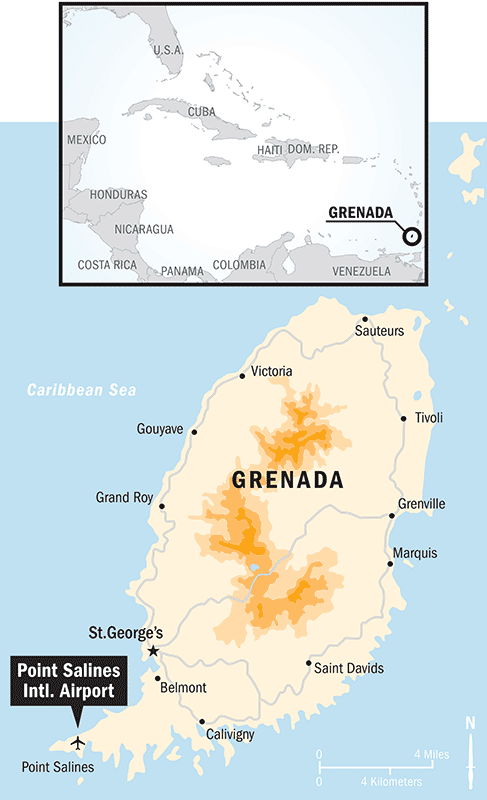

Located 100 miles north of Venezuela, Grenada is the most southerly of the Caribbean island chain known as the Lesser Antilles. Roughly twice the size of the Washington DC metropolitan area (131 square miles), Grenada is a densely populated island with nearly 90,000 inhabitants.3 It was part of the British Commonwealth, with the Queen represented by a Governor-General. Enrolled in the St. George’s University Medical School on the island were over 600 Americans. The American student population was largely composed of individuals who had not gained entrance into medical schools in the United States and were trying to improve their chances.4 Their presence was a significant factor when political unrest rocked the island.

On 19 October 1983, a coup led by General Hudson Austin overthrew the government of Prime Minister Maurice Bishop. The People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA) replaced Bishop’s Marxist government with a more virulent Marxist regime. The PRA executed Bishop and a number of his top political allies. Austin and a sixteen member Revolutionary Military Council (RMC) swiftly took control of the country. Monitoring the situation on the island, the United States intelligence community was aware of a large number of Cuban military on the island. They were engineers primarily engaged in the construction of a 10,000-foot concrete runway capable of handling heavy military planes. The runway represented an opportunity for the Soviet Union to extend the range of their Tupolev “Bear” reconnaissance aircraft into South America. This upgrade of the island’s landing facilities, coupled with the uncertainty over the safety of the American medical students on the island, was sufficient for President Ronald Reagan to authorize the use of military force in a non-combatant evacuation operation.

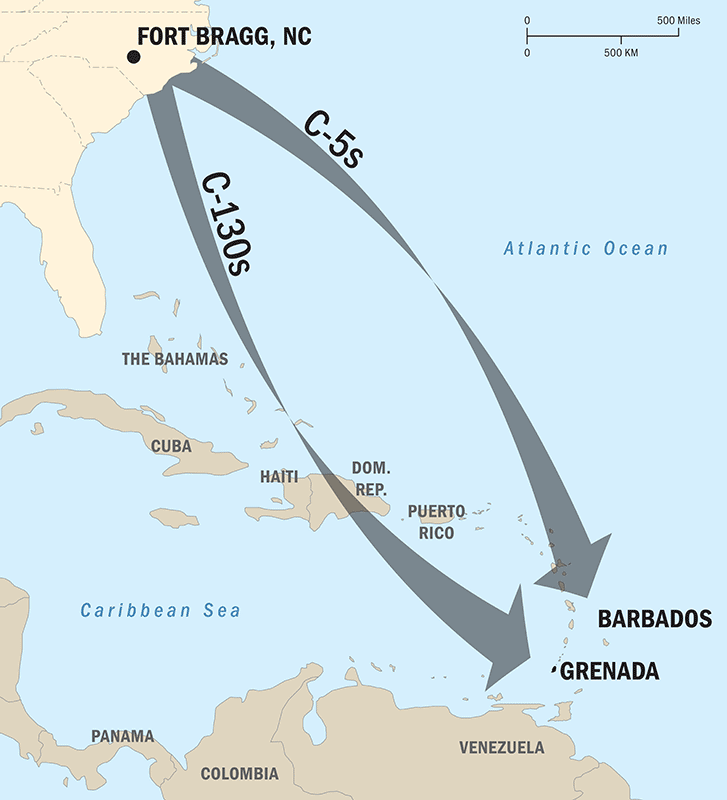

When alerted in the middle of the night on 21 October, Chief Warrant Officer Dave Bramel and the other Task Force 160 UH-60 Black Hawk pilots and crewmembers initially believed that this was another exercise. The crews loaded the nine Black Hawks on the C-5 aircraft at Fort Campbell for transport to Pope Air Force Base, North Carolina, and then on to the staging area on Barbados. It quickly became clear to all that this was not a routine exercise. Other elements of the Task Force were also on recall.

On 22 October at Yuma Proving Ground, Arizona, instructor pilot Chief Warrant Officer 2 Jim Dietderich was flying an MH-6 with student pilot Warrant Officer Mike Gwinn in the Weapons and Tactics Instructor Course when they were notified to return immediately to Fort Campbell. On the plane flying back, Dietderich noticed the news headlines about the bombing of the Marine barracks in Lebanon and assumed that this was where they were headed. The two MH-6 Little Bird pilots grabbed their personal equipment at Fort Campbell and caught a flight the next morning to Fort Bragg, North Carolina.5 There they linked up with the other elements of the Task Force.

“When we got to Fort Bragg, there was a distinct sense of urgency,” David Bramel recalled.6 Bramel and the other pilots went into the mission briefing. “The G-2 (security) guy giving us the intelligence briefing told us that there were ‘no more than six Cubans on the island. You guys will have the people waving at you as you come on shore.’ The mission was to kick the Cubans off Point Salines Airfield. There was no mention of medical students.”7

The lack of potential opposition was accentuated when Bramel and the other pilots were issued .38 caliber pistols as side arms. “The guy issuing the weapons gave me six rounds and told me I needed to return them after the mission as it [the ammunition] was all from a single lot and accountable.”8 On the UH-60s, two pintle-mounted M60 machine guns manned by the aircraft crew chiefs provided the protection for the aircraft. After the mission briefing, the pilots went back to the flight line where they linked up with the special operations troops that would ride in on the helicopters. “Before we left, we all got down and drew some sketches in the dirt to get a basic idea of how we were going to execute this thing.” Bramel thought to himself that it “was just like when I was in Vietnam.”9

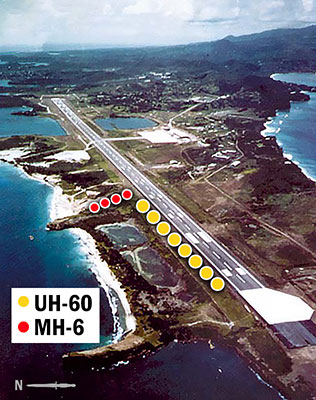

At Pope Air Force Base, the nine UH-60’s were on the C-5 aircraft of the 436th Military Airlift Wing that picked them up at Fort Campbell for the flight to their destination on the island of Barbados. At the same time, two AH-6 and six MH-6 Little Birds were loading on four C-130s.10 The C-130s were to fly directly into Point Salines Airfield on the heels of the Ranger parachute assault. The Rangers who would ride the MH-6’s loaded onto the aircraft with the Little Bird crews. All the C-5s with the Black Hawks were airborne by 2000 hours on 24 October, less than forty-eight hours after being alerted. The C-130s with the Little Birds followed in the early morning hours of the 25th, headed directly to Point Salines.11

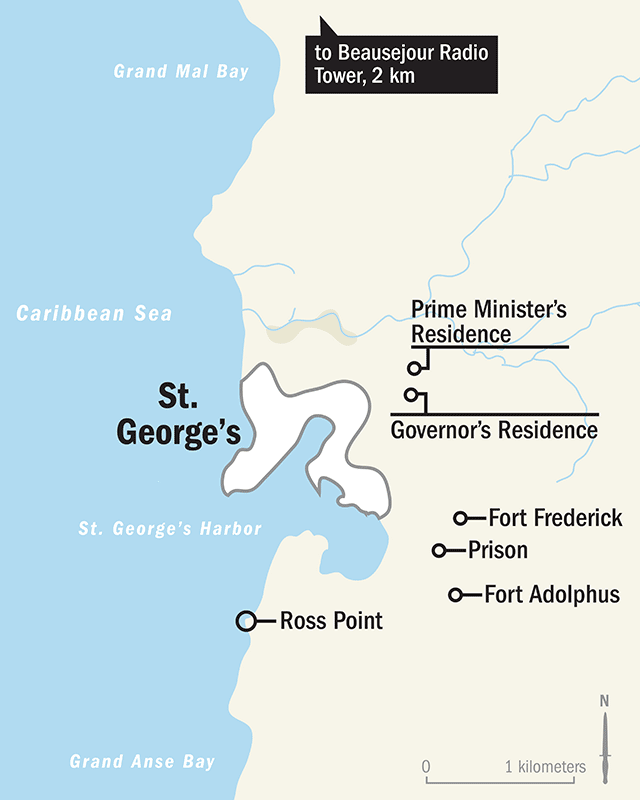

Task Force 160 had three primary objectives in the invasion of the island. The UH-60 aircraft were to insert special operations forces at Richmond Hill Prison; at the Governor’s mansion to rescue Sir Paul Scoon, the Governor-General; and at the island’s radio and television broadcasting station at Beausejour. The MH-6s would insert the Rangers at secondary targets in the city of St. George’s. The original mission called for the insertions to occur at 0100 on the 25th, five hours after leaving Pope Air Force Base, to take full advantage of the darkness and TF 160 pilot expertise in flying with night vision goggles. Delays with the Air Force aircraft, chaotic pre-mission planning, and inter-service staff inefficiencies caused the time schedule to unravel. The three C-5s landed on Barbados between 0250 and 0330 and despite an all-out effort by TF 160 to get the UH-60s built-up and ready to go, the helicopters did not depart until 0530, as daylight was spreading over Barbados.12 By the time the helicopters lifted off on the 45-minute flight to Grenada, the invasion by conventional forces was underway; the special operations forces would not catch the enemy by surprise.

As the aircraft raced toward Grenada, the pilots tuned in to the local radio station where, to their dismay, they heard the announcer telling the local populace to get their weapons and shoot down the American helicopters that were approaching.13 Despite a prohibition against test firing the weapons on the run in to the targets, the pilots immediately had their crews fire their M60s in preparation. They discovered that the ammunition for the machine guns was regular link instead of the required mini-gun ammunition, which caused the weapons to jam.14 As the nine aircraft neared the island, five Black Hawks headed for Richmond Hill Prison initially followed by the two aircraft assigned to carry troops to the Governor’s mansion. These two then broke off short of the prison and headed for the Governor’s mansion. The remaining two Black Hawks headed toward the radio station as the flight came onto the island.

Richmond Hill Prison represented a formidable target. Perched on a high ridge that ran like a spine north and south a kilometer above the capital city of St. George’s, the prison boasted walls twenty feet high, topped with barbed wire and watchtowers. There were no landing zones on the narrow, twisting ridge and the intent was to insert the special operations troops using the fast roping technique pioneered by TF 160. The intelligence report was that the prison was serving as the headquarters for General Austen’s RMC and likely to be well guarded. To make matters worse, 500 meters to the east and 150 meters above the prison loomed Fort Frederick, headquarters for the People’s Revolutionary Army.15 The positioning of the two compounds caused the helicopters to fly through a gauntlet of fire. As the flight of Black Hawks in trail rounded a large hill and began their approach, they came under withering fire from troops in and around the prison. All helicopters sustained damage with virtually every crewmember being wounded.

“They were ready for us,” Bramel recounted. “We stabilized to fast rope, but never did execute. I looked down to my right and there was a Cuban guard with an AK-47 and he was just ripping my aircraft apart … We were there for about five seconds, maybe ten seconds, and I said ‘Don’t go, don’t go.’ We went back around and, I’m not sure if we got this from the ground commander, but we went back in. They had more people waiting for us this time. We went back to the same spot and the same guard is there hammering my aircraft.”16 Bramel took a round in the leg that knocked his foot from the pedal. Major Larry Sloan, the company commander, was in the jump seat and was hit in the back by a round that would have caught Bramel in the head. One of the special operators leaned out of the doorway and shot the Cuban guard.17 The Black Hawk pilots frantically cleared the area without discharging any passengers.

Bramel recalls, “The fire was unbelievable. I made a call over the radio and said ‘I’m gone’ and out I went.” The Black Hawk flown by Chief Warrant Officer Paul Price and Captain Keith Lucas headed away from the prison at the same time. Bramel remembers his exit from the scene, “I must have passed low and quick by the ADA site [on Fort Frederick] and they didn’t see me. They picked up Price’s aircraft. I could see dirt coming off the aircraft from all the rounds hitting it. It just inverted and went into the trees.”18

Captain Keith Lucas aboard the downed aircraft was killed by gunfire on the run past Fort Frederick. Three other soldiers were killed when the aircraft crashed on Amber Belair Hill. The rest of the passengers and crew struggled under heavy enemy fire to get away from the aircraft. Navy helicopters later evacuated them after the Rangers and more special operations personnel came in to secure the crash site. Lucas proved to be the only fatality suffered by TF 160 during URGENT FURY.19

The other four aircraft repulsed from the prison headed out to sea full of wounded. When safely offshore, the pilots spotted a Navy warship, the USS Guam and the flight headed for it. The helicopters circled the ship and Bramel landed his Black Hawk on the deck despite the frantic attempts by the vessels’ crew to wave off the helicopter. “I landed and the ‘air boss’ came storming over ready to tear a piece off of me and these wounded guys just came falling out. With that they got the medical teams involved and each aircraft landed in turn.”20 The helicopters, at this point barely airworthy, headed back to Point Salines Airfield. They were too badly damaged to make the flight back to Barbados.

Point Salines had not been secured at the time the Black Hawks arrived. The pilots parked their aircraft on the left side of the airfield by a sand berm and shut down. The helicopters immediately attracted small arms fire, and Bramel and the other aircrews did what they could to take a defensive posture. “We took our M60s and deployed them and, of course, I had my .38 with six rounds. About that time I looked up and here comes this big formation of C-141s carrying the Rangers in for the drop on the airfield.”21 With the Rangers on the ground controlling the airfield, the flight of four Black Hawks from the mission at Richmond Hill Prison remained on the airfield. The other TF 160 Black Hawks fared somewhat better with their missions.

Sir Paul Scoon, the Governor-General of Grenada, and his wife and staff were awakened early on the morning of the 25th by the sound of approaching helicopters and the rattle of small arms and air defense artillery fire. Two helicopters of TF 160 arrived overhead carrying special operations troops. On the first attempt to fast rope the troops on to the mansion grounds, intense fire forced the pilots to abort and return to the carrier USS Guam and off load a number of wounded.

They then made a second attempt; twenty-two special operators successfully fast roped onto the grounds of the mansion and secured the building and the Governor-General. The plan called for the team to await the arrival of ground forces later in the day rather than try to evacuate the Scoon party by helicopter.22 The ground team soon found itself in a pitched battle with the PRA who moved an armored personnel carrier up to the gates of the mansion grounds. An AC-130 Spectre gunship arrived on station to even the odds and hold the attackers at bay. As with the special operations forces on the ground, the AC-130 was operating in daylight due to the late start of the operation. The special operators held on through the night and were relieved the next day. The two Black Hawks returned to Point Salines Airfield. Things did not go so well for the team inserted to seize the radio transmitter.

The remaining two Black Hawks of the task force carried special operators whose mission was to land and secure the Beausejour radio and TV station. The pilots had no difficulty identifying the target that was set a few hundred meters up from the beach. The troops exited the aircraft and dashed in to secure the building. Holding the building proved difficult. The team encountered heavy resistance throughout the day, and eventually was driven off the site by an armored personnel carrier. They abandoned the transmitter building and worked their way down to the beach, where after dark they swam back to the destroyer USS Caron.23 The two Black Hawks returned to Point Salines and remained with the other six on the island as night fell.

At the airfield, the Rangers methodically expanded their holdings and steadily pushed the PRA back. The Black Hawks waited out the rest of the night at Point Salines. The next day they were joined by the Little Birds, the other task force element heretofore not engaged.

On the 25th of October, two AH-6 and six MH-6 Little Birds were unloaded from the four C-130s at Point Salines near the Air Terminal. Prior training sessions with the Rangers on build-up procedures paid off as the Little Birds were quickly made combat ready. The Black Hawk pilots warned their Little Bird counterparts of the hostile environment over the city. The Little Birds’ first mission was short-lived. As the two AH-6 aircraft crested the hills above Point Salines and headed out over the bay, they encountered intense fire and quickly returned to the airfield. Fully alert, they used a different approach route and subsequently provided very effective suppressive fires during the recovery of the men and equipment from the downed Black Hawk on Amber Belair Hill.24 The volume of fire encountered by the AH-6’s over the city caused the Ranger insertion mission by MH-6’s to be cancelled.

Chief Warrant Officer 2 Dietderich and the MH-6 teams displaced from the airfield apron where they had off-loaded, and moved their helicopters and the Rangers to a more protected position in a draw at the far end of the airstrip. One MH-6 was damaged in the maneuver when the tail rotor hit on the uneven ground. With their pre-planned mission scrubbed, the MH-6 Little Birds remained on the airfield as the Rangers and then the newly arrived troops of the 82nd Airborne Division expanded the perimeter around Point Salines.25 Two of the AH-6 crew chiefs, Sergeant Steven R. Nelson and Sergeant David L. Godsey, hot-wired a bulldozer on the airfield and built a berm to store the AH-6 ammunition.26 The Little Birds remained in place until the next day when they assisted the medical personnel of the 82nd by evacuating wounded from the airstrip.

On the morning of 26 October, the second day of operations, the MH-6 pilots responded to the 82nd’s request for evacuation of several wounded soldiers. The pilots loaded up the wounded and flew them out to the USS Guam. “The Guam was supposed to be our support ship, but we didn’t know where it was and we did not have the proper frequencies to talk to the Navy,” recalled Jim Dietderich. “Once the Guam moved in and we could see it, we flew out there and off-loaded the wounded. We hadn’t trained on the protocols for landing on a carrier and to me it looked like a long floating runway, so I came in from the rear and just set down in the middle of the deck.”27 The five MH-6s made three round-trips before they were pulled off the mission to reload their helicopters aboard two C-141s for a flight back to the United States.28 The UH-60s also received the word that they were return to Barbados.

In the afternoon of 26 October, the Black Hawk pilots were told to fly back to Barbados that night. Five of the aircraft were badly damaged and required extensive repairs. They did receive one replacement rotor blade via a C-130 to replace one severely damaged over the prison. By parking a hot-wired steamroller alongside the aircraft, they were able to get the blade installed that afternoon.29 Despite the battle damage to the helicopters and low fuel levels, particularly in Bramel and Chief Warrant Officer 4 Marc Moller’s aircraft, the flight of eight Black Hawks left that night for Barbados. Unescorted by safety aircraft, the flight had no self-recovery capability. With damaged instrumentation and little in the way of functioning navigation systems, the flight followed a rough azimuth until they saw the glow of the lights of Barbados. Bramel’s aircraft crossed over the shore on the verge of running out of fuel. He quickly looked for a suitable landing spot. As the aircraft came to a hover, one engine flamed out, and as the helicopter settled down, the second engine died.30 Later, they loaded the aircraft on C-5s and returned to Fort Campbell.

For Task Force 160, Operation URGENT FURY validated the training programs that produced the most experienced professional pilots and crews to survive in the hostile environment over Grenada. Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Henry H. Shelton, described the Night Stalkers: “Throughout the short history of the 160th, its aviators have pioneered night flight tactics and techniques, led the development of new equipment and procedures, met the call to duty wherever it sounded, and earned a reputation for excellence and valor that is second to none.”31