DOWNLOAD

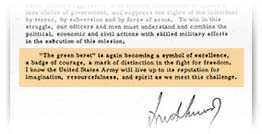

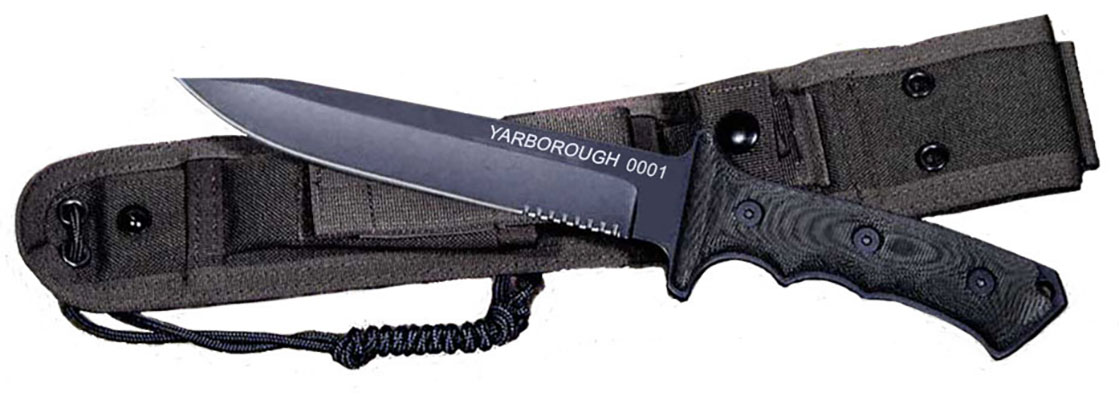

When Lieutenant General William P. Yarborough passed away on 6 December 2005, he left a remarkable legacy of innovation, creative intellectual energy, and professional accomplishment. In a career that spanned thirty-seven years of service to the Army, and more as a civilian consultant and lecturer, LTG Yarborough made an indelible mark in the airborne, psychological warfare, and special operations arenas. The visible signs of his impact on the Army special operations forces community—the Green Beret, the Yarborough Knife, and the Parachutist Badge—are the physical manifestations of a career made noteworthy by his insatiable pursuit of improved doctrines and equipment for the soldiers with whom he served. As described by Brigadier General John Mulholland, Commanding General of United States Army Special Forces Command, “He was one of our titans.”1

LTG Yarborough graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1936. Among his classmates were William Westmoreland, Creighton Abrams, and Benjamin O. Davis. His first assignment was in the Philippines where he served with the 57th Infantry, Philippine Scouts. In 1940, he returned to the United States to Fort Benning, Georgia, where he joined the 501st Parachute Infantry as a company commander and test officer in the fledgling Provisional Parachute Group.2

Shortly thereafter, while awaiting his Russian visa to be assigned as a military attaché in Moscow, he received orders to report to England as the airborne planner on the staff of Major General Mark Clark. The staff was engaged in planning Operation TORCH, the Allied invasion of North Africa. Yarborough later recalled, “I was picked by General Mark Clark to become part of the London Planning Group to address airborne operations.” In the early years of the war, Yarborough was one of the few officers with sufficient background in airborne operations and Clark intended to conduct an airborne “insertion” as part of the invasion. “I suppose because I was extremely enthusiastic about airborne operations, and maybe having been one of the early officers in this activity, he felt I was qualified to do this.”3

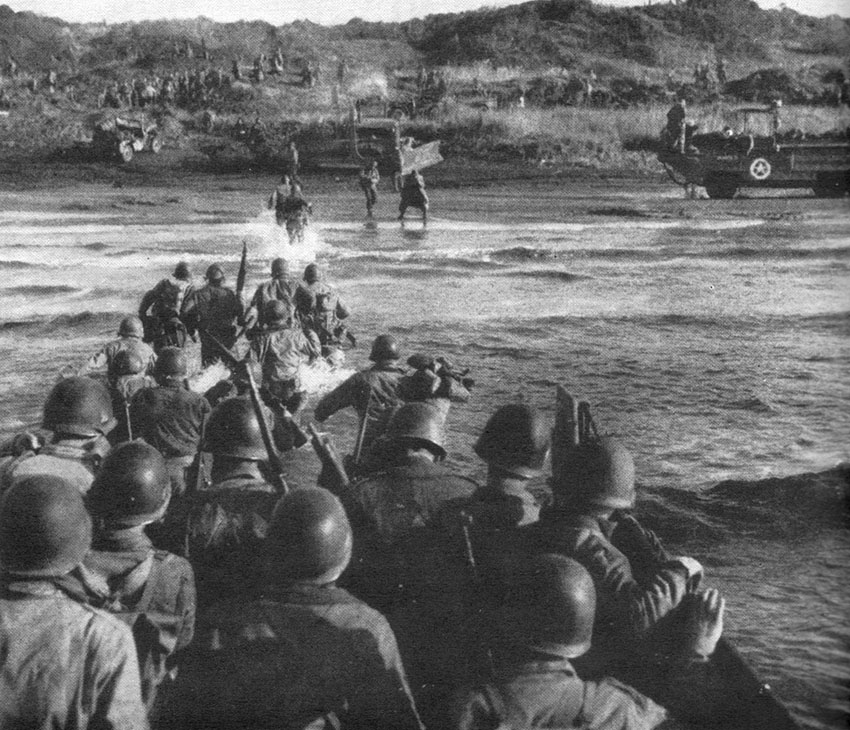

Joining Clark’s staff at #1 Cumberland Place, London, in July 1942, Yarborough was caught up in the feverish planning for the invasion. The first U.S. combat parachute assaults ultimately proved to be some of the longest and the most complex airborne operations of the entire war. Operation TORCH called for the Parachute Task Force led by Colonel William C. Bentley Jr., Army Air Corps, to fly 1,500 miles at night from England across Spain and the Mediterranean Sea to airdrop on the airfields of Tafaraoui and La Senia near Oran, Algeria. Major Yarborough was to be the “eyes” of MG Clark and accompany the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Edson D. Raff.4

It was during the pre-invasion training and the chaotic operations in Algeria that Yarborough formed his strong opinions about the role of airborne and Ranger forces. These opinions became part of his core philosophy and he applied them in his later assignments. “Paratrooper is a frame of mind … Being surrounded by the enemy doesn’t in the least mean that the game is up.”5

He saw the distinct roles of the Rangers, the airborne, and what would eventually become Special Forces in the operations behind the lines:

“When we first began the parachute units, when we had the 501st Parachute Battalion, we considered that more in the line of a combination of Ranger–Special Forces than we did straight-leg infantry arriving by air. The philosophy we built into those outfits was that wherever you land, you are liable to land in the wrong place. It’s a coin flip. You are to do the kind of damage to the enemy that you are trained to do and don’t let it worry you that you may end up in two’s and three’s or a half a dozen.”6

MG Clark next sent Yarborough back to the United States, ostensibly to command a battalion in the 101st Airborne Division. Major General Matthew B. Ridgway, the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, rather summarily diverted him to Fort Bragg, North Carolina. In retrospect, Yarborough felt his experience in airborne operations was being ignored by the planners of the 82nd. As a result, he deployed to Tunisia for the airborne assault into Sicily with a significant chip on his shoulder. “I was sort of a young man’s prima donna, felt kind of dumped on, and my feelings were hurt … I was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 504th, which I commanded and went back overseas with the 504th. [COL] Reuben Tucker was the Regimental Commander and he had been an old friend of mine, but I was so intractable and so impossible that even Reuben Tucker felt that he had a burr under his saddle.”7

During the operations in Sicily, Yarborough ran afoul of MG Ridgway on several occasions. His actions and attitude caused him to be relieved by Ridgway. When his unit reached Palermo, he was told to report to the commanding general. Ridgway told him, “Your services are no longer required. You’re a pain in the a——, excuse me, but you go back to Mark Clark and tell him that he should find another job for you.”8 In retrospect, Yarborough said, “I had paid the price for my high-spirited stupidity. Challenging authority in [that] way … no outfit can work on that basis … It was with me, not Ridgway or Tucker.”9

Eventually Yarborough was given command of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion and led that unit during the fighting around the Anzio beachhead. His leadership style epitomized the “spit and polish” of the airborne and was in stark contrast to that of another elite unit commander, Colonel William O. Darby of the Rangers. “I had known Darby before and had a high regard for him. But mixing paratroopers and Rangers was like mixing oil and water. Here we went in for the traditional esprit of the soldier based on the customs of the service, even in the shell holes. Every man shaved every day no matter what. Our people looked sharp. I required it and they took pride in the parachute uniform and the badge they had. Darby’s guys looked like cutthroats. They looked like the sweepings of the bar rooms.”10

Contrasting his unit and Darby’s, Yarborough explained the differences between elite units and how leadership approaches and specialized techniques are required to effectively lead each. “Darby and I used to sit around and talk about this phenomenon and we both agreed that one should approach leadership from two points of view when we have an extraordinary kind of a mission to perform. One was the traditional one, which I preferred, and the other was his approach which offered only blood, sweat, and tears for the right kind of guy.”11

With the end of war, Colonel Yarborough faced a situation entirely different from leading paratroopers in combat. His next assignment was as the Provost Marshal of the American forces in the divided city of Vienna, Austria.12 He moved from the hot war against the German Wehrmacht to the Cold War against the Soviet Union. His experiences in Europe over the next decade helped to shape his perception of unconventional warfare and codify his perception of the role of Special Forces.

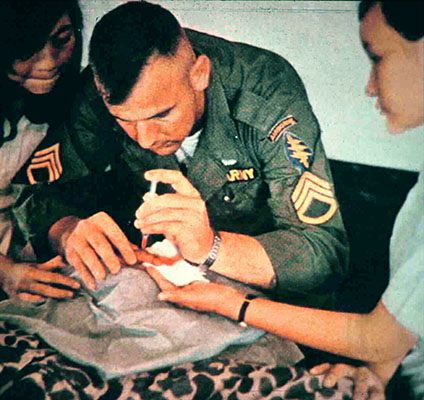

Post-war Austria and its capital city of Vienna were divided among the four Allied powers—Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States—like in Berlin. As the American Provost Marshal, COL Yarborough dealt daily with the problems of rebuilding Austria amid the turmoil of U.S. Army demobilization and the intransigence of the Soviets. Yarborough recognized from the beginning of his tour the need to have highly-qualified soldiers in the ranks of his constabulary force. These men were required to deal with the most sensitive and highly charged situations on a daily basis. Maturity and intelligence were critical for Constabulary troops.