NOTE

USSOCOM PAO guidance on current operations dictates the use of pseudonyms for SOF majors and below. Those individuals identified by true name in previously published news articles are the exception.

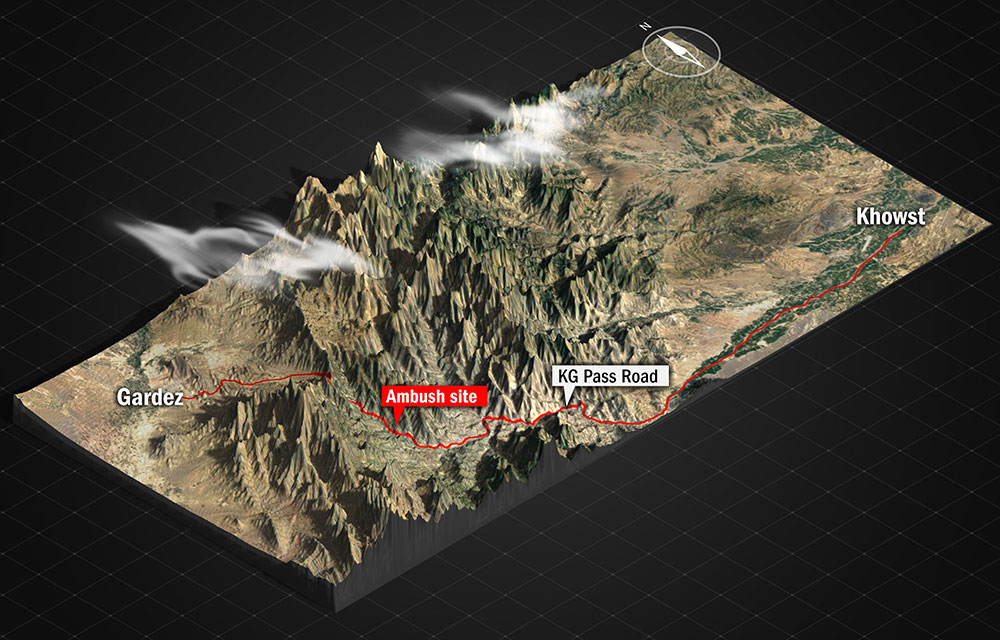

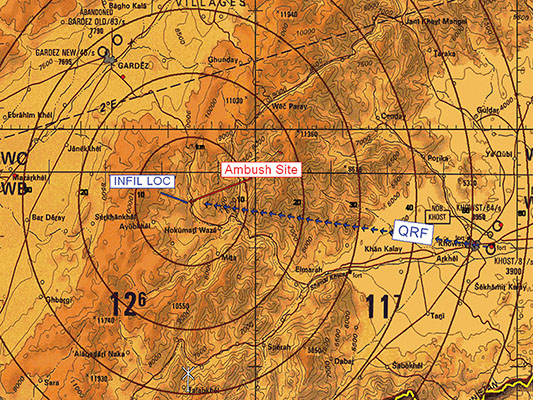

In the morning of 11 April 2005, al-Qaeda–associated militia ambushed an Afghan military convoy escorting General Khil Baz, former 25th Infantry Division commander, to Gardez. The ambush occurred northwest of the village of Barak Kalay on the Khowst–Gardez road, near the pass. Rocket-propelled grenades (RPG) and small-arms fire stopped the Afghan Security Force (ASF), inflicting minor damage on the vehicles. The 45-man ASF dismounted and returned fire, but were unable to maneuver against the well-positioned attackers. The steep, rugged terrain found in this area adjacent to the Pakistan border was popular for “hit and run raids and ambushes.”1 General Baz quickly called for assistance using his satellite telephone.

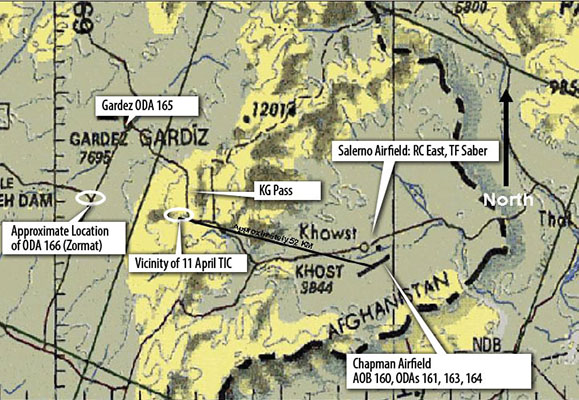

U.S. Army Special Forces ODA 163 and a Khowst Provincial Force (KPF) platoon located at Chapman Airfield were the chosen Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force–Afghanistan (CJSOTF-Afghanistan) QRF (Quick Reaction Force). The two forces were ready and closest to the ambush site. Nearby at Fire Base Salerno UH-60 Black Hawk and AH-64 Apache helicopters from Task Force (TF) Sabre were on alert.2 A rapid response enabled the QRF to find, fix, and engage the ambush perpetrators several kilometers from the ambush site. The enemy was caught by the lead element of the reaction force before it could escape and a fierce firefight erupted. Air Force Close Air Support proved ineffective against enemy positions hidden in the scrub vegetation on the reverse slopes of steep, narrow fingers that dropped down into deep ravines. Fighting in the rocky, mountainous terrain at 8,200 feet was tough. After three hours of heavy fighting, thirteen al-Qaeda–associated militia fighters were dead; three Americans and one KPF Afghan were wounded.3 This joint Coalition QRF mission was well directed by the SF ODA detachment commander using appropriate coordination, control, and support provided by all levels of command.

The 30 May 2006 Army Times article, “There Was a Lot of Shooting: Soldiers Honored for Heroic Assault During Clash in Afghan” by Michelle Tan, briefly synopsized the three-hour action. It focused on two ODA 163 soldiers and a 23rd Special Tactics Squadron (STS) airman who were awarded Silver Stars and a Bronze Star for Valor.4 That synopsis did not do justice to this multi-faceted, complex action. The purpose of this article is two-fold: to provide “the rest of the story” on an action effected by an experienced, well-trained SF team (supported by a courageous Black Hawk aircrew), and to highlight a well-executed mission by the 1st Special Forces Group (SFG) during its first Operation ENDURING FREEDOM (OEF) rotation in Afghanistan.5

Appreciating and understanding the harshness of the steep terrain, factoring how close the fighting was, the limited visibility between combatants on the ground—the enemy, SF team, KPF, and Navy SEAL platoon—corresponding actions, and the experience of the ODA are critical to understanding what happened when, and why. Thus, a sequential presentation of the events that lays out the actions by the various higher headquarters will be used to reconstruct a very complicated fight and the appropriate responses. This narrative focuses on ODA 163.

Team members, as well as higher commanders and staff, explained their Afghanistan missions and their specific roles during the QRF fight on 11 April 2005. In this combined action, SF and joint commanders at all levels coordinated staff actions appropriately to support the action without imposing on the ground commander directly involved commanding the fight.6 The smooth support rendered by all levels illustrates why this particular Coalition joint action is important to the Force. Prior to discussing the details of the 11 April 2005 action, it is important for context to know the background of the 1st SFG’s involvement in OEF-Afghanistan, its mission, and its pre-deployment preparations and training.

The decision by U.S. Army Special Forces Command that 1st SFG would provide its 2nd Battalion to support the CJSOTF in Afghanistan was made on 7 June 2004. When Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Kirk H. Nilsson, a twelve-year 1st SFG veteran, assumed command of the 2nd Battalion two weeks later, he knew they were going to Afghanistan in December to support the 7th SFG. Colonel Jeffrey D. Waddell, the 7th SFG commander, assigned his 1st Battalion the OEF mission in Regional Command (RC) South and West. While the staff prepared the campaign plan, the 2/1 SFG ODAs focused on critical skills needed to survive on the battlefield—ground mobility vehicle crew-served weapons fire and maneuver, 81mm mortar refresher, communications, and tactical medical training. The high-desert, mountainous area of Yakima, Washington, proved ideal.7

After the August 2004 site survey, the 2/1 ODBs focused on their specific areas of operations. ODB 160 had the Khowst–Gardez bowl (the center sector) while ODB 140 concentrated on the northern sector of RC East. “The battalion training scenarios were built to concentrate on a lot of collective tasks simultaneously,” stated LTC Nilsson. “As it happened, the requirement to field an ODB for a late-September Combined Training Center rotation meant that A Company (ODB 140) was the last 2/1 element deployed to Afghanistan.”8

To cover the area of operations of RC East properly in accordance with Joint Task Force 76 (JTF-76) guidance “to get SOF [special operations forces] on the border areas,” Colonel Waddell realigned CJSOTF forces. 2nd Battalion, 1st SFG [Forward Operating Base (FOB) 12] would command three AOBs (advanced operating bases): two organic and Company C (AOB 730) from the 7th SFG. In this way, a single commander could focus on RC East and the Pakistan border areas. Based on the number of ODAs, team strengths, and special skill levels, Nilsson assigned the center sector—the Khowst–Gardez area—to Company C, 2/1 SFG (AOB 160).

The 25th Infantry Division Artillery, or TF Thunder, the conventional force in RC East, had positioned 105mm artillery in two-gun sections on/near the SF bases and a battery of 155mm artillery to support the Afghan border control posts (BCPs). The regional commanders supported provincial reconstruction teams with missions to promote local governance and stimulate infrastructure rebuilding.9 When the ODAs were operating in areas or BCPs beyond the fire base artillery fans, 155mm two-gun sections were often “jumped” by helicopter to cover the gaps in coverage.10

For the CJSOTF, this was an economy-of-force decision. Since infiltrations could not be prevented, they could at least deny sanctuary. The BCPs reduced freedom-of-maneuver to larger enemy forces intent on massing to attack. Instead of a 360-degree fight, the engagements would be more like 180-degree fights on the Afghan border. This meant very active vehicular patrolling by the ODAs during the winter months.11 Operating in the harsh winter weather common in the mountainous border region became routine for the ODAs based around Fire Base Chapman.

ODB 160 had the largest sector, containing the Afghan border control posts that had received attacks the most often. Major Jack Spartan* had hoped to use General Khil Baz to help stand up an effective paramilitary force to secure the border areas.12 Since ODA 163 responded to attacks on BCP 6, the model for future Afghan posts, it initially assumed the FOB QRF for the border and then the entire Khowst–Gardez area. Despite the fact that ODA 163 had been in-country for four months, it rehearsed QRF actions weekly, and was “spun up” fifteen times for missions not executed. Due to those factors, Master Sergeant (MSG) Paul Cooper, team sergeant, constantly stressed immediate action drills, scheduled firing to maintain weapons battle sights, practiced artillery and close air support direction, and inspected individual equipment for readiness. Having worked in the Khowst–Gardez area on a previous deployment, Cooper and his ODA commander, Captain (CPT) Brett Dandridge*, worked out a solid “game plan.”13

Every BCP, village, and city in their assigned sector had been visited multiple times, each time accompanied by the local commander of the Afghan Security Forces (ASF). “We put a ‘host nation face’ on everything that we did,” said MSG Cooper. “We got our Civil Affairs teams to fund wells and schools and arranged Medical Readiness and Training Exercises. In conjunction with these, we became familiar with the terrain and improved our situational awareness. By riding armed aerial reconnaissance flights, we were able to select multiple routes to and from BCPs. As a result, we located the Taliban and al-Qaeda LOCs [lines of communication] in our zone.”14 Perimeter security for the fire bases and the QRF mission entailed training up ASFs for their defensive and offensive roles.

Recruiting, training, and organizing local ASFs and training KPFs to support a QRF were implied ODA 163 missions. A day-long mini-selection course reduced the mostly illiterate fifty candidates down to the best thirty. Then, a mile run, followed by an obstacle course, identified those recruits who had the most heart and intestinal fortitude to finish training. Some cursory background checks determined honesty and integrity. During “basic training,” personnel were regularly rotated through leadership positions to identify the platoon and the squad leaders. The leaders received more pay than the privates. The smartest recruits received medical and demolitions training and were awarded “proficiency” pay and “bonuses” for outstanding jobs. These incentives leveled the economic playing field between ASF and KPF soldiers.15 The ODA 163 “game plan” was to have the ASF and KPF well trained before the spring thaws came in March, when stay-behind al-Qaeda and Taliban militia fighters were normally resupplied to conduct guerrilla operations in the warmer months.

Having been “spun up” fifteen times before, individual QRF equipment was pre-positioned and ready when CPT Dandridge was summoned to the ODB operations center by MAJ Spartan. Every man carried two basic loads of ammunition for the QRF mission. They also wore Level 4 body armor. With “Go” bags carried onboard the helicopters, the ODA could operate independently for twenty-four to thirty-six hours.16

“Mobility and maneuver were part of every fight,” said MSG Cooper. “The team was quickly assembled and alerted. While they ‘kitted up’ and checked weapons, CPT Dandridge and I waited for the execute order in the Ops Cen [operations center].”17 KPF with advisors and interpreters “rounded out” the QRF. UH-60 Black Hawk and AH-64 Apache aircrews at nearby Fire Base Salerno had begun pre-flight checks of their aircraft.

The ODB 160 commander, MAJ Spartan, knew that General Khil Baz was a friend of Coalition forces and that when working with Afghan forces, rapid responses to calls for assistance were important to garner loyalty and build confidence. After discovering that the conventional TF Thunder QRF at Fire Base Salerno was not readily available, and knowing that response time was critical, Spartan queried ODA 165 as to its ability to do the mission. It was only thirty miles away from the ambush site. Captain Jerry Harkins*, the ODA commander, responded that based on road conditions and steep terrain, it would take his element two hours to drive through the mountains to the ambush site.18

MAJ Spartan then called FOB 12 because the ambush was outside ODB 160’s battle space. As the request sped up the chain of command (from FOB 12 to the CJSOTF-Afghanistan to JTF-76), it was fortunate that JTF commander, Major General Jason Kamiya, happened to be visiting Fire Base Salerno. Though the ambush site was in the battle space of the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment (3/3 Marines), Kamiya assigned the mission to the SOF QRF. They already had forces postured to execute. TF Thunder and 3/3 Marines would be in support.19 In the short time it took to gain approval (less than twenty minutes), FOB 12 had alerted the Fire Base Salerno helicopters and close air support “on station” of a potential mission.20

Planeside at Chapman Airfield, Dandridge and Cooper briefed the QRF with the details of the mission. “We were to find, fix, and destroy the enemy ambush force. We got the usual ‘pump’ that came with ‘action outside the wire.’ The team always went out prepared … expecting a firefight,” said Staff Sergeant (SSG) Matthew Marco*, the junior 18C engineer.21 As rehearsed, ODA 163 divided into two elements and boarded the Black Hawks; the KPF elements followed.22

In the first aircraft, CPT Dandridge would stay airborne for command and control while the second helicopter carrying Chief Warrant Officer 2 (CW2) Anthony C. Stencill*, the detachment executive officer, and MSG Cooper landed first to investigate. By the time the UH-60s lifted off from Chapman Airfield, two A-10 Warthogs and the two Apaches were already en route to the ambush site thirty minutes away. When the Black Hawks were fifteen minutes out, the AH-64s provided an exact grid location for General Baz’s convoy on the Khowst–Gardez road (easy to spot by the Jinga trucks stacked up on both sides of the ambush site) and reported no sign of attackers in the immediate area.23

Lacking communications with General Baz, CPT Dandridge directed CW2 Stencill to land near the stalled convoy. He was to confirm that Baz was alive, ascertain whether or not he wanted a ride out of the mountain pass, and collect specifics on enemy exfiltration routes. Dandridge would overwatch the meeting from his aircraft and pass up-to-date information to AOB 160 and FOB 12. All higher commands closely monitored the situation.24

General Baz gave more than a direction where the enemy withdrew—he identified the exact finger that the enemy had used and the amount of time that had elapsed since the ambush. Baz declined a ride saying that “he had to demonstrate to everyone that he was still ‘the man’ in the valley.” Other than bullet holes in a few trucks, the Baz convoy was relatively unscathed. Based on these specifics, Air Force Technical Sergeant (TSgt) Bradley Reilly [Combat Control Team] called the A-10s (BOAR 01 and 02) and AH-64s (CARDPLAYER) to narrow their search patterns on enemy egress routes heading southwest.25 Considering the steepness and severity of the terrain, and the time elapsed since the enemy’s withdrawal, the helicopter-borne QRF had a chance to catch the escaping enemy fighters. The chase was on!

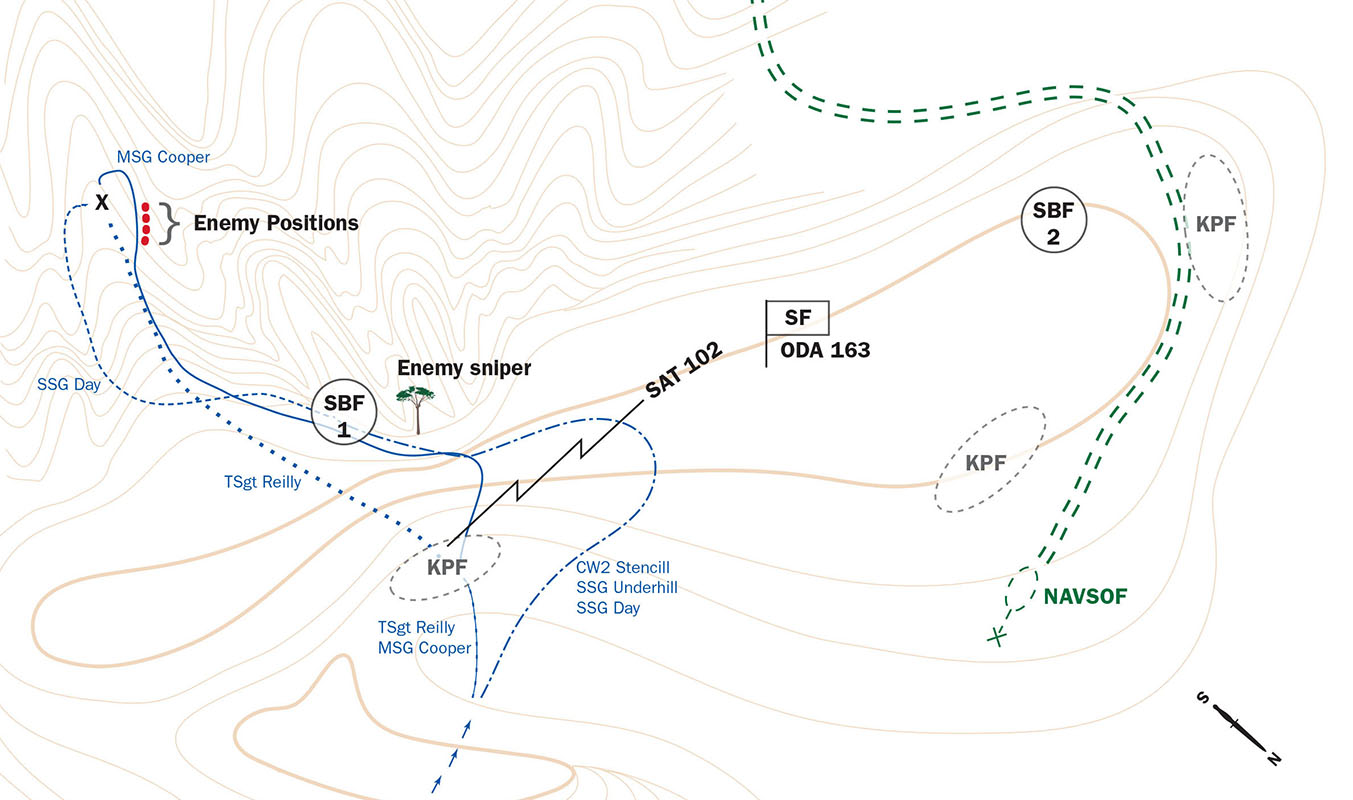

Five minutes after the Black Hawks left the ambush site, one of the AH-64s sweeping the area reported spotting three personnel carrying AK-47s and RPGs. They were walking in a draw using the vegetation to conceal their move. Since this was a very complex fight in very rugged and convoluted mountainous terrain, the following is a visual image of what CPT Dandridge saw as he approached the target area from the north:26

A large exaggerated “C-shaped” flat butte that was slightly tilted down to the west was the dominant terrain feature. There was a shallow bowl in the “cup” of the “C” between arms. Numerous steep, narrow-ridged fingers with rocky ravines in-between dropped from the south side of the butte. The high-desert, rocky, mountainous terrain (8,200 feet) had scrub evergreen vegetation scattered about and rock outcroppings and abutments along the ridges and crests. The suspected al-Qaeda militia fighters had been spotted near the top arm of the “C.” 27

CPT Dandridge had the pilots of his Black Hawk, SKILLFUL 12, cautiously overfly the suspected area to confirm the sighting. Dandridge told CW2 Stencill to prepare to land offset of the suspected enemy. Stencill’s pilots, in the Black Hawk SKILLFUL 31, literally blew one fighter’s blankets off to reveal an AK-47 and several RPG rounds at his side. The door gunners were trained on the suspect.28

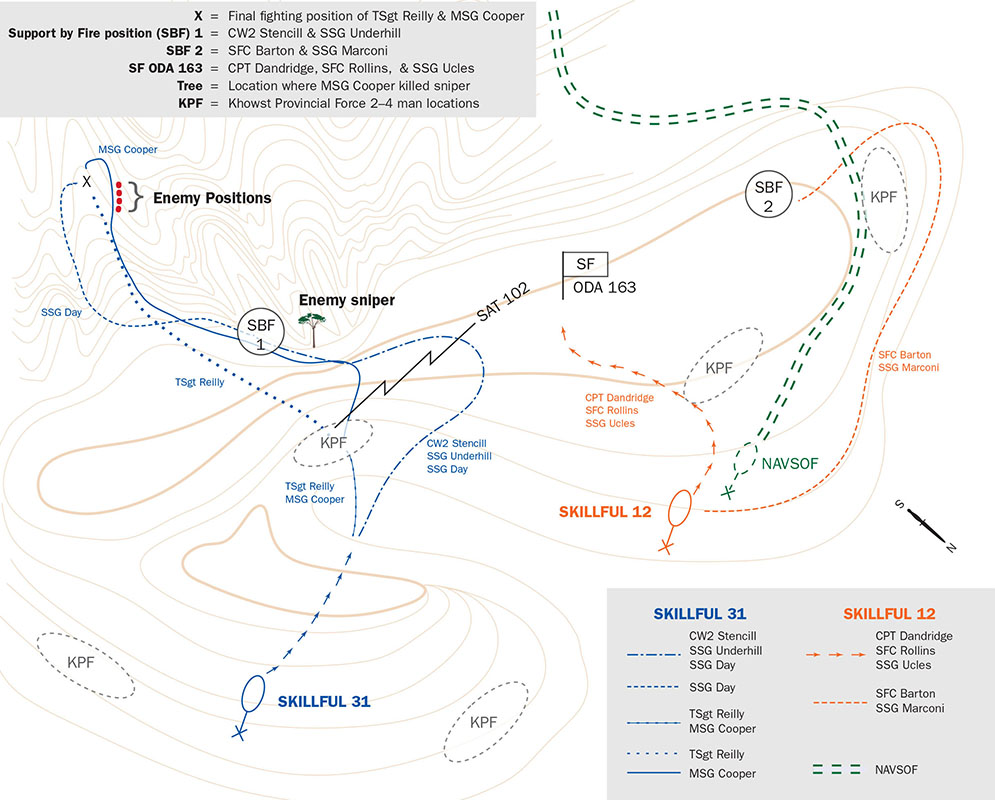

Suspicions confirmed, CW2 Stencill had SKILLFUL 31 land on the reverse slope of an adjacent hilltop (north reverse slope of the bottom arm, parallel to the ridge with a single aircraft wheel on the hillside), while requesting that the AH-64s engage the enemy fighter with the RPG rounds.29 SKILLFUL 31 hovered while Stencill, MSG Cooper, TSgt Reilly, Staff Sergeant Jubal Day (team medic), Staff Sergeant Nate Underhill*, and seven personnel from the KPF element jumped down (eight to ten feet) to the ground and established 360-degree perimeter security. As the UH-60 lifted off, one enemy fighter jumped up and sprayed the landing site with automatic AK-47 fire.30 “With rounds coming in, that helo blew out of the LZ [landing zone],” remembered Cooper.31 Dandridge, above, quickly relayed: “Troops in Contact (TIC).”32 The fight was on!

As the detachment commander searched for a place to land his helicopter, Cooper, Reilly, and four Afghans fired and maneuvered south and slightly east as Stencill, Day, Underhill, and the remaining KPF started moving and clearing the western flank of the bottom arm of the “C” using the available scrub brush as cover. Enemy machinegun fire concentrated on the military crest of that arm. As Cooper’s force swept through a depression on the reverse slope of the finger (the shallow bowl in “cup” of the “C”), it noted the still-warm remains of several cooking fires. Before sweeping the left of the front ridge (upper arm of the “C”), Reilly requested that AH-64s make several 30mm chain gun runs along the crest. After receiving Stencill’s initials (because their attacks would be “Danger Close”), the two Apaches commenced to attack with cannon and rockets. The gun runs started small fires along that crest.33

The smoke provided cover, but the fires started by the Apaches dictated directions of maneuver during the assault to clear the left part of the front ridge (top arm of the “C”). As MSG Cooper crested the hill, a machinegun opened up on him. Fortunately, the gunner was firing high. As he dropped to the ground, Cooper pulled out a grenade and threw it toward the enemy position. After detonation, Cooper jumped up to assault forward, killing the enemy gunner with his M-4 carbine. As MSG Cooper was relaying a quick report to CW2 Stencill, SKILLFUL 12 was flaring to insert CPT Dandridge and his element to the west of Stencill and Cooper on a small hillock (reverse slope of the upper arm of the “C”). Cooper and two KPF Afghans were securing the eastern half of the front ridge line. They provided overwatch as TSgt Reilly and two KPF Afghans investigated a sighting further down a southerly finger to Cooper’s left front.34