SECTIONS

RELATED

DOWNLOAD

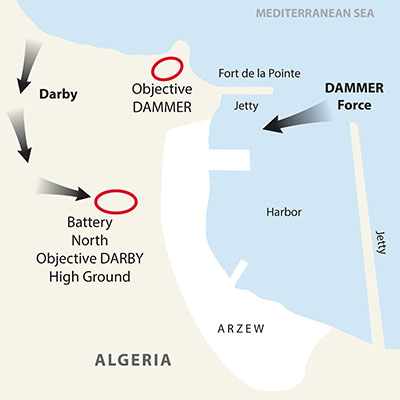

The 75th Ranger Regiment, consisting of three battalions and the regimental headquarters, evolved from the experiences of the U.S. Army in World War II. At the onset of the War, the Army had no units capable of performing specialized missions. By the end of the War, the Army fielded seven Ranger infantry battalions (the 1st through the 6th and the little known 29th) that conducted operations in North Africa, the Mediterranean, France, and the Pacific (the Philippines). The purpose of this article is to explain how the Rangers came to be in WWII, in particular those units formed in Europe and then committed to North Africa. Future issues of Veritas will include articles on Ranger operations in Sicily and Italy, France, and the Philippines (the 6th Ranger Battalion).

Darby and the 1st Rangers are Formed

The U.S. Army did not have special operations units in 1941. That quickly changed when America declared war on the Axis and entered WWII. Brigadier General Lucian K. Truscott Jr., the U.S. Army liaison with the British Combined Operations Headquarters, proposed to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall on 26 May 1942 that “we undertake immediately the organization of an American unit along [British] Commando lines.”1 A cable quickly followed from the War Department to Major General Russell P. Hartle, who was commanding the U.S. Army Forces in Northern Ireland, authorizing the activation of the 1st Ranger unit.2

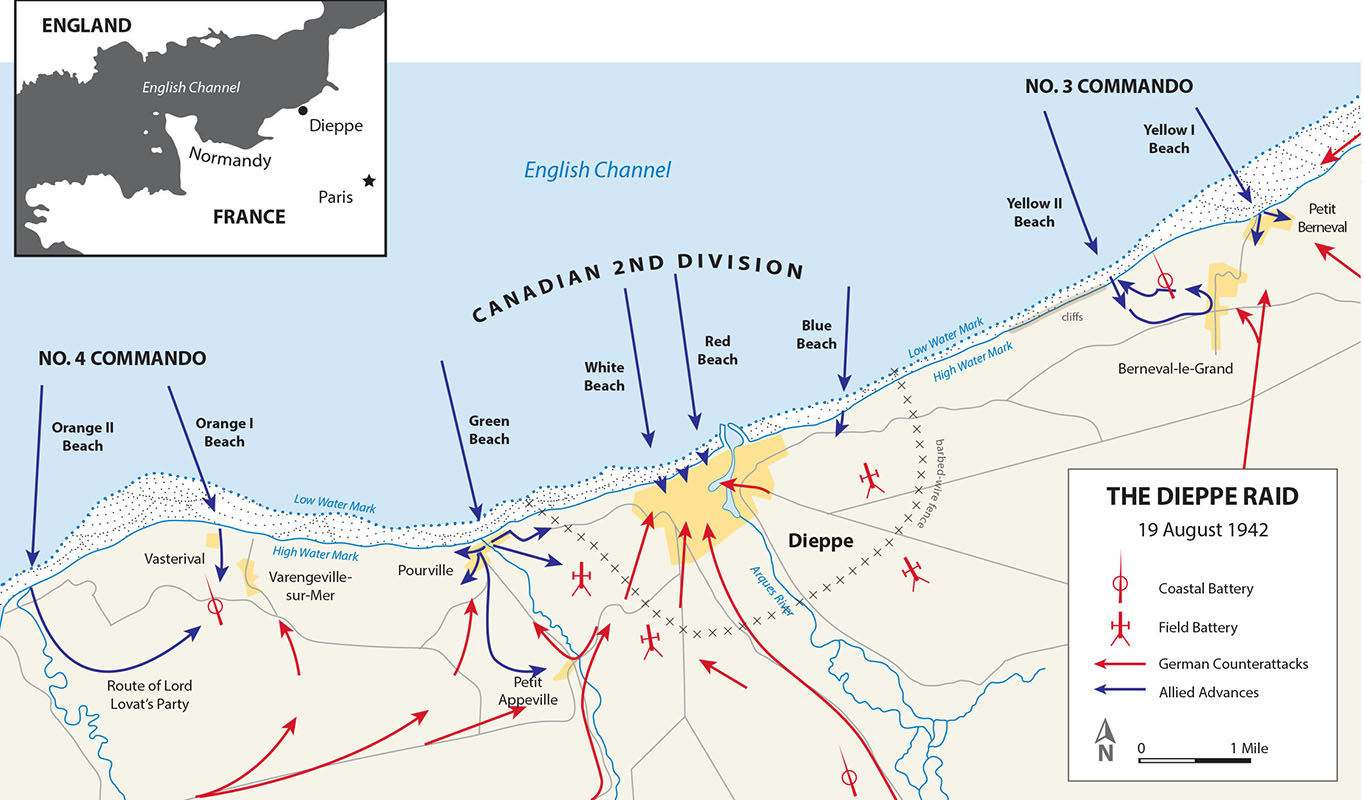

The original idea was that the 1st Ranger Battalion would be a temporary organization to disseminate combat experience to new American troop units.3 The battalion would have detachments temporarily attached to British Commando units when they raided German-held countries in Europe. Then, the combat-tested, or “blooded,” soldiers would return to their units to share their experiences.4 Soldiers would be cycled through Commando training and return to the United States to train additional troops.5

Lieutenant General Truscott selected the title “Ranger” because the title “Commando” belonged to the British. He wanted a more fitting American moniker. “I selected ‘Rangers’ because few words have a more glamorous connotation in American military history … It was therefore fitting that the organization destined to be the first of the American ground forces to battle Germans on the European continent in World War II should be called Rangers—in compliment to those in American history who exemplified such high standards of individual courage, initiative, determination and ruggedness, fighting ability, and achievement.”6 While Truscott was a student of military history in 1940, the movie “Northwest Passage,” staring Spencer Tracy and Robert Young, was popular and may have contributed to his choice of name. Based on the Kenneth Roberts’ novel, the film extolled the exploits of Roger’s Rangers in the French and Indian War with Spencer Tracy playing Major Robert Rogers.7

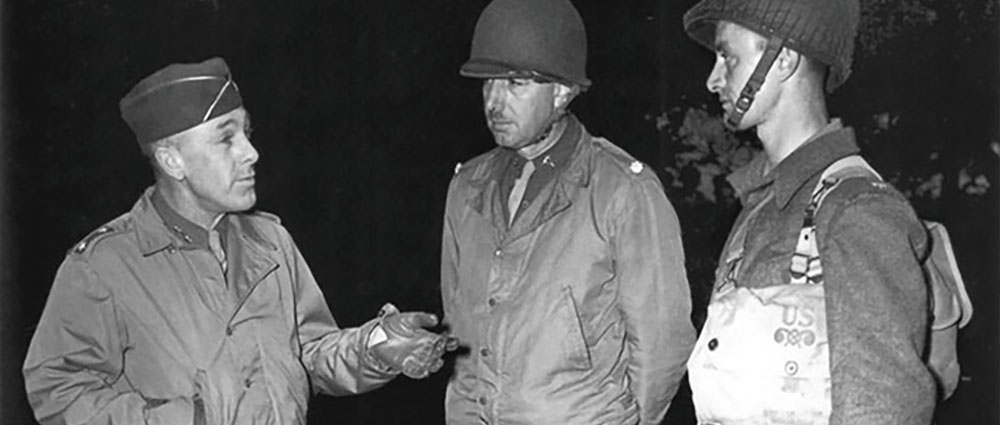

Once the decision was made to form a Ranger battalion, the next task was to select a commander. After some deliberation, Major General Hartle nominated his own aide-de-camp, Captain William Orlando Darby. An artillery officer, Darby had cavalry and infantry operational experience as well as amphibious training. Truscott was receptive, finding the young officer to be “outstanding in appearance, possessed of a most attractive personality, and he was keen, intelligent, and filled with enthusiasm.”8 His judgment of suitability proved accurate. The 31-year-old Darby, a 1933 graduate of West Point, demonstrated an exceptional ability to gain the confidence of his superiors and earn the deep devotion of his men.9

Promoted to major based on his selection for battalion command, Darby immediately began organizing his new combat unit. Soon flyers calling for volunteers appeared on U.S. Army bulletin boards throughout Northern Ireland.10 Darby “spent the next dozen days [personally] interviewing the officer volunteers and, with their help, some two thousand volunteers from V Corps … in Northern Ireland—looking especially for athletic individuals in good physical condition.”11 The recruits, ranging in age from seventeen to thirty-five, came from every part of the United States. Most of the Ranger recruits joined because they wanted to be part of an elite force. Some units did try to unload misfits and troublemakers, but they were usually rejected and sent back.12

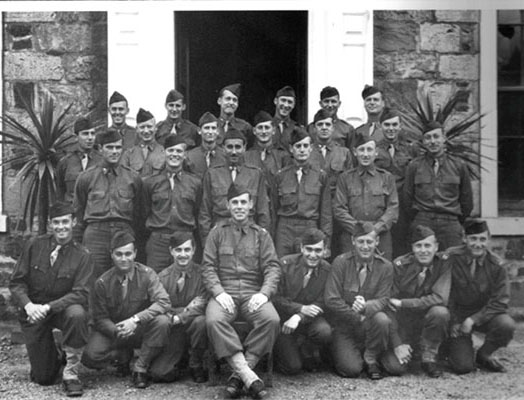

The 1st Ranger Battalion was formed with volunteers from the following units: 281 from the 34th Infantry Division, 104 from the 1st Armored Division, 43 from the Antiaircraft Artillery units, 48 from the V Corps Special Troops, and 44 from the Northern Ireland base troops.13 After a strenuous selection program to weed out unfit soldiers, Truscott activated the 1st Ranger Battalion on 19 June 1942, at Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland, a town twenty miles north of Belfast.14

With considerable foresight, Darby was allowed a 10 percent overstrength for rejections and injuries in the tough training program to come. Five hundred seventy-five recruits began training at Carrickfergus. Darby could only retain 473 (26 officers and 447 men). These became the original members of the 1st Ranger Battalion.15

The Rangers were organized almost exactly like the British Commandos. The term “commando” connoted a battalion-sized unit of specially trained soldiers and, at the same time, the individual soldiers were called “commandos.” Each company had a headquarters of three (company commander, first sergeant, and runner) and two infantry platoons of thirty men each. The battalion consisted of a headquarters company with six line companies of sixty-three to sixty-seven men. The Ranger battalions sacrificed administrative self-sufficiency for foot and amphibious mobility.16 Once the recruitment, organization, and assignments had been completed, the Rangers headed for Scotland for phase one of their training.