DOWNLOAD

Since 1950, Colombia has traditionally supported the United Nations collective security initiatives. The Colombian Navy and Army provided combat elements to serve with the UN Command in Korea. Both were “showcase” forces representing the best of each service and the nation.1 Colombia was the only Latin American country to send military forces to support the UN effort to counter North Korea’s invasion of South Korea on 25 June 1950.2 The professionalism developed by Colombian military leaders in Korea enabled them to turn their armed forces into a respected modern military. This transformation also fostered social and political changes in Colombia. The purpose of this article is to show what the Colombian Navy did during the Korean War.

Just as the U.S. “first response” to Korea was its Pacific Fleet, so it was for Colombia in 1950. Within two days of the invasion, the Security Council had passed two resolutions that committed the UN to halt the aggression. The armed invasion of South Korea was deemed a “breach of peace.” Member states were asked to refrain from assisting North Korea. The second UN Security Council resolution asked the member nations to provide military assistance to South Korea to repel North Korean aggression and to restore international peace and security. The Colombian delegation played a key role in garnering support for the resolutions. It proved most convenient that the Soviet Union delegation was boycotting the Security Council. The Soviet Union had absented itself since January 1950, to protest the seating of Nationalist China while excluding Communist China.3 Stopping the aggression of North Korea became a test of the UN peacekeeping ability.4

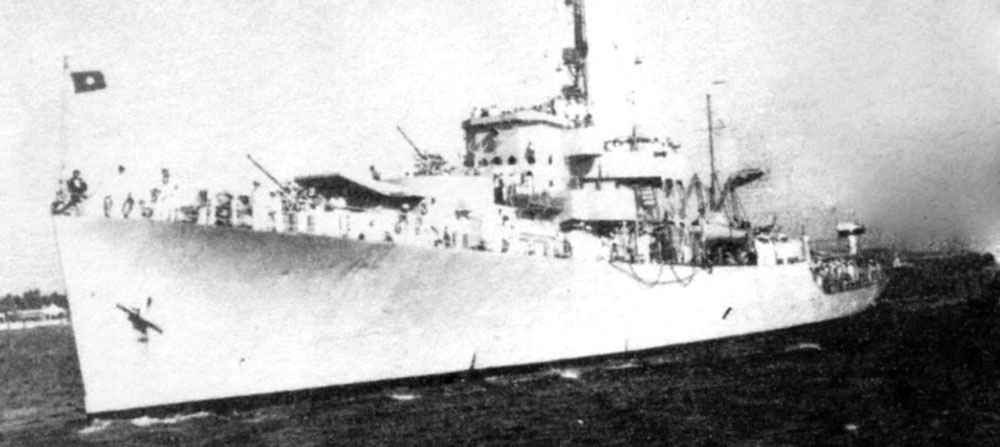

In Bogotá, the editors of the Conservative newspaper, El Siglo, vied with those at El Tiempo in advocating Colombia’s obligation to furnish military forces to the UN.5 The decision to support the UN fight in Korea had to wait until the inauguration of Laureano Gómez Castro in August 1950. On 6 September 1950, the new president pledged a frigate to the UN Naval Command.6 This was quite significant because the entire Colombian Navy consisted of two 1932-vintage Portuguese destroyers captured during the war with Peru, a 1944 U.S. Tacoma-class patrol frigate (former USS Groton—renamed Almirante Padilla) purchased in 1947, and ten river gunboats.7

The authority to dispatch the Frigata Almirante Padilla overseas was by Executive Decree No. 3230 (25 October 1950) because the national state of emergency declared by Mariáno Ospina Pérez, the predecessor of Gómez, was still in effect. The suspension of all congressional activities had been imposed to stem La Violencia.8 On 1 November 1950, the frigate Almirante Padilla, with a crew of 190 (ten officers and 180 seamen), steamed out of Cartagena bound for San Diego Naval Base, California, for combat refitting.9

Though the Colombian government hoped the frigate would be in the war zone by the end of the year, the crew left knowing that neither they, nor their frigate was ready for combat. “Much to my surprise, two hours after leaving Balboa, Panama Canal Zone, for San Diego, I asked for fifteen knots. I was speechless when my chief engineer told me that the machinery was too bad and that we could only make ten knots,” recalled Lieutenant Commander (Lt Cdr) Julio Cesar Reyes Canal. When the Korean War began, Lt Cdr Reyes Canal, a navy officer with thirty-two years of service, was in the process of resigning to protest cuts in the naval forces. At the time the entire defense budget amounted to a paltry 1.1 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP).10