DOWNLOAD

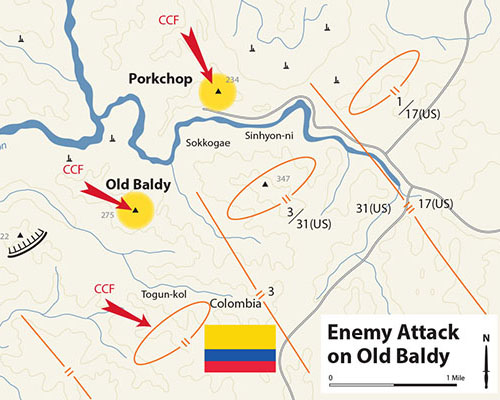

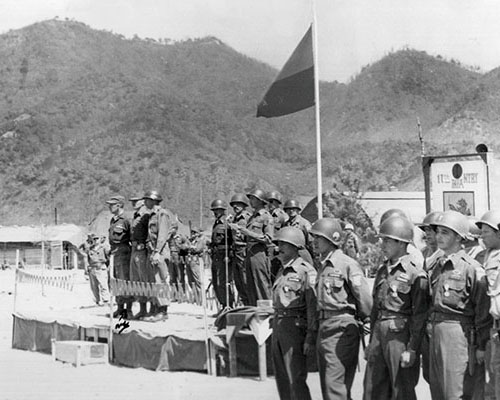

Colombia provided an infantry battalion and a frigate to serve with the United Nations Command in Korea from 1951–1955. It was the only Latin American country to provide forces.1 The Batallón Colombia bravely fought the Communist Chinese in numerous engagements in 1951 and 1952, earning a U.S. Presidential Unit Citation during the Kumsong Offensive. However, it was the heavy fighting in March 1953, while the peace talks were in progress, that truly tested the mettle of the South Americans. This article will focus on the two most significant actions of the Batallón Colombia in Korea, Operation BARBULA and the fight for Old Baldy. In a period of ten days, the Colombians suffered 114 killed, 141 wounded, and 38 missing in action, the equivalent of two rifle companies.2 The purpose of this article is to place those two battles in proper context in order to show how earlier success in Operation BARBULA created conditions that contributed later to a controversial loss.

This study is relevant because the Korean War was key to the development of a professional Colombian armed force and was a benchmark in the social and political transformation of the country. Because Colombia was the only Latin American country to support the principles of international, collective security in Korea, the Batallón Colombia and its naval frigates became “showcase” elements for their military services, the nation, and the Americas.3 When the Batallón Colombia reached the front lines on 1 August 1951, the war was a stalemate.

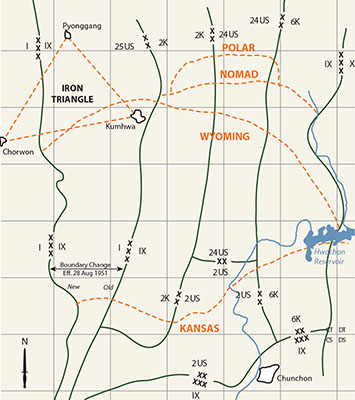

The UN objective in Korea had shifted from military victory to a political settlement. The Eighth Army commander, U.S. General James A. Van Fleet, concluded that “continued pursuit of the enemy was neither practical nor expedient. The most profitable employment of UN troops … was to establish a defense line (Line Kansas) on the nearest commanding terrain north of Parallel 38, and from there push forward in limited advances to accomplish the maximum destruction to the enemy consistent with minimum danger to the integrity of the UN forces.”4

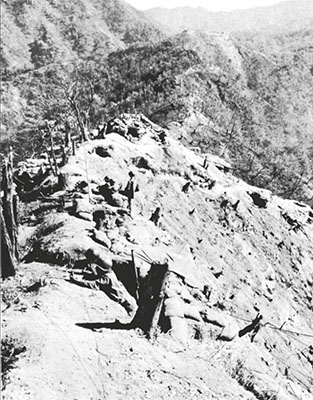

That meant Line Kansas was to be fortified in depth. Hasty field fortifications would be constructed along the forward slopes of Line Wyoming [Combat Outpost Line (COPL)] to blunt enemy assaults and delay them before they reached Kansas, the main line of resistance (MLR). Having trained to fight offensively, the Batallón Colombia would primarily defend. Only limited attacks would be conducted against the Chinese forces.5 Attached to two different U.S. divisions (21st Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division until late January 1952; then to 31st Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division until October 1954), the Colombians would defend the MLR and conduct patrols and raids between the lines until the armistice on 27 July 1953. However, while peace talks were ongoing at Panmunjom, the Chinese launched a major offensive in the spring of 1953, to capture several UN outposts on dominant terrain that overlooked the MLR.6

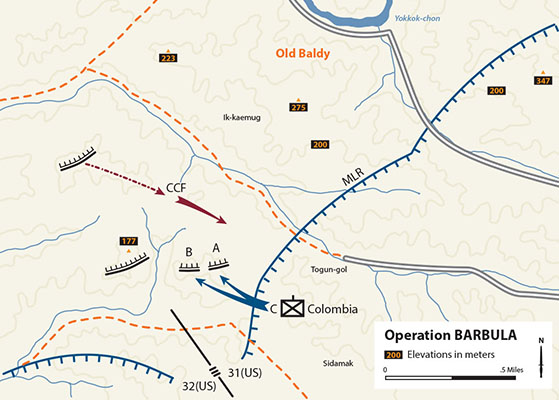

When the 7th Infantry Division returned to the MLR the end of February 1953, it had been reassigned from the IX Corps to the I Corps sector. The Batallón Colombia was operationally ready. The battalion’s intense integrated training of 201 replacements from the 8th contingent was key to Colonel William B. Kern awarding it a top performance during regimental maneuvers in late November 1952, and again in February 1953.7 Operation BARBULA placed the Colombians back into the ground war.