DOWNLOAD

Since World War II, Colombia has supported international collective security through the United Nations and regionally with the Organization of American States (OAS). Colombia provided a naval frigate and an infantry battalion to serve in Korea with the UN Command for four years. In 1956, President Gustavo Rojas Pinilla sent Batallón Colombia to serve as part of the UN Emergency Force (UNEF) to defuse the Suez Crisis. Colombia, as an original signatory of the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance [commonly known as the Río Treaty (1948)], mobilized its armed forces in support of the OAS naval quarantine of Cuba during the Missile Crisis in 1962. Hemispheric defense was the basis of the Río Treaty; aggression against one is considered to be an attack against all member states.1 Since 1982, Colombia has supported the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) in the Sinai with an infantry battalion (Batallón Colombia) and selected officers, the UN Observer Mission in El Salvador (UNOSAL), and the UN Protection Force in the former Yugoslavia (UNPROFOR).2

The purpose of this article is to briefly explain the Colombian military missions with the UNEF during the Suez Crisis of 1956 and with the MFO in the Sinai since 1982. Colombia has supported the principle of collective security since the end of World War II. Its Army and Navy forces fought with the UN Command in Korea to halt Communist aggression. Since the Korean War, the Colombian Army has been providing international peacekeeping forces and observers. These highly sought after overseas assignments have been career enhancing and an opportunity to escape the domestic violence endemic to Colombia since La Violencia began in 1948.

1950–1953

1953–1957

In the first months after overthrowing the regime of President Laureano Gómez, General Rojas Pinilla dramatically reduced the domestic violence. However, by early 1954, the country was again deep in guerrilla war, more localized in rural areas, but equally bloody. The National Police were taken out of the fight and the Army thrown in shortly before the return of Batallón Colombia from Korea. As Colonel Alberto Ruíz Novoa (second commander of the Colombian battalion and then Minister of War) and the other veterans of Korea rose rapidly to positions of responsibility, these leaders soon lost confidence in their former chief, who had evolved into a self-aggrandizing, despotic dictator ruling on whim. His days as president were numbered when, in a last ditch effort to regain military support, he committed the Batallón Colombia by executive decree to the UN for the Suez Crisis in 1956.4 The Army leadership, unwillingly involved in the domestic conflict, welcomed the UN mission. The crisis over the Suez Canal was an opportunity to divert the soldiers’ attention from the violent war in the countryside.

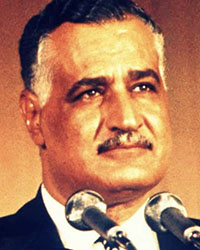

The Suez Crisis of 1956 erupted after Anglo-French air forces bombarded Egyptian military targets before parachute assaults were made into Port Said and Port Faud. British and French paratroopers seized control of the Suez Canal on 31 October 1956. Two days before Israel had invaded the Sinai Peninsula. The rationale given for these acts of aggression were President Gamal Abdul Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal Company, Egyptian and United Arab Republic (UAR) encouragement of Algerian nationalism, Egypt allowing Arab guerrilla training bases in the Gaza Strip, and Nasser’s threat to deny universal passage through the Suez Canal.5

During a 3–4 November 1956 all-night meeting of the UN General Assembly, the delegations from Canada, Colombia, and Norway drafted a joint resolution calling for a UN military task force to supervise a “cessation of hostilities” in the Suez. Colombian delegate Francisco Urrutía recommended that a “safety cordon” be established around the Gaza Strip by stationing UN troops along the frontier. The decision to provide a military unit to the UN raised little public interest in Colombia. The military regime did not need popular support to send its forces abroad. And, the Suez Crisis was not related to the country’s domestic disorder.6

Military support to a UN mission, as it was during the Korean War, was one of the few issues on which most Colombian politicians were in agreement in 1956. Offers of troops were made by twenty-four countries. Only ten were accepted. By 11 November 1956, forces from Canada, Colombia, Norway, and Denmark were assembled at Capodichino, near Naples, Italy. Within days, the contingents were flown by Swissair into Ismailia, Egypt, to form the UN Emergency Force (UNEF), commanded by Canadian Major General E.L.M. “Tommy” Burns, the former Chief of Staff of the UN Truce Supervision Organization.7 It was UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold who called the “Blue Helmets” the “first truly international force” because it eventually contained Communist, non-Communist, and neutral forces. After the Anglo-French invasion force was pressured to withdraw in late December 1956, the greatest potential spot for trouble was the Israeli-Egyptian border. The Brazilian, Indian, and Colombian battalions and a Swedish company were spread along the armistice demarcation line, called the Gaza Strip. The Colombian patrol sector until late October 1958 was the Khan Yunia zone.8

The UNEF mission was basic peacekeeping. The combined UN force monitored the French and British withdrawals and phased Israeli pull-back across the Sinai. UNEF assumed relief operations and administrative responsibility for the Gaza Strip. The forces of UNEF established observation posts and conducted patrols along the Gaza demarcation line and the international frontier in the Sinai between Israeli and Egyptian military forces. The Batallón Colombia of 490 officers and men sailed for Colombia on 28 October 1958, after nearly two years of peacekeeping duty.9 It would be twenty-four years before Colombia accepted another peacekeeping mission.

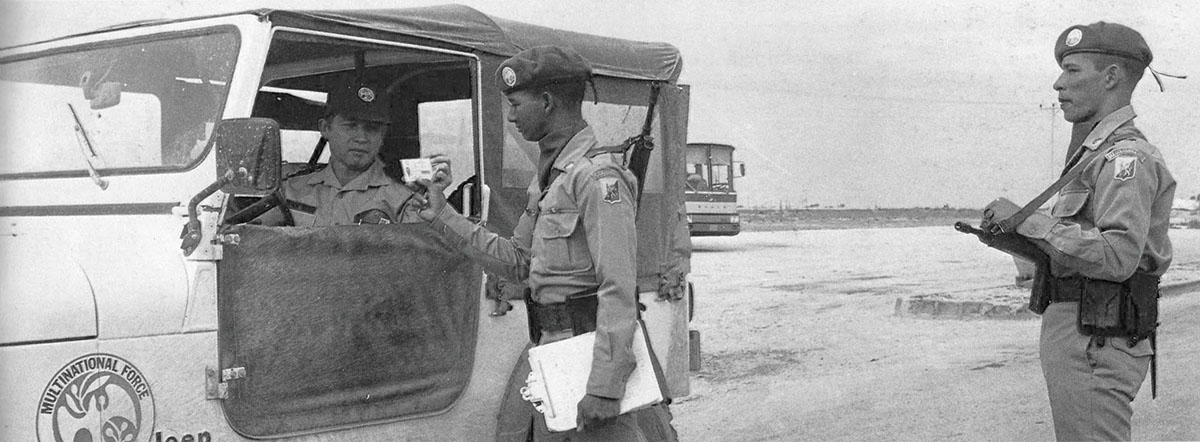

Colombia has provided an infantry battalion and officers to the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) mission since 1982. The MFO is an independent, international peacekeeping organization funded equally by Egypt, Israel, and the United States. It does not act as a buffer between Egyptian and Israeli forces nor as an instrument of interim or truce arrangements, but rather works closely with the two nations to support a permanent peace.10 Colombian Army soldiers and civilians (31 officers, 58 non-commissioned officers, 265 soldiers, and 3 civilians) are assigned to the Sinai mission for eight-month tours; half of the element rotates every four months.

The mission of the Batallón Colombia is to observe and report any activities in the Central Sector of Zone C, according to the Sinai Treaty and Protocols, and to guard the North Camp, El Gorah, located on the northeast side of the Sinai border. The battalion also provides medical and dental officers, a force liaison officer, a force security officer, and fourteen soldiers to augment the Multinational Force staff. The Batallón Colombia accomplishes its peacekeeping observation mission by stationing elements of two infantry companies at seven remote sites throughout the Central Sector of Zone C, on the eastern border of the Sinai. Since the remote sites always have to be permanently manned, temporary observation posts and motorized patrols ensure wide coverage and continuous observation. Colombia is justifiably proud of its MFO mission in the Sinai that promotes peace and stability in the Middle East.11

These two international peacekeeping missions reflect the continuous commitment of Colombia to world peace through international collective security. Batallón Colombia first became an instrument of Colombian foreign policy during the Korea War. Today, Batallón Colombia is still charged with that responsibility in the Sinai with the MFO.