DOWNLOAD

La Escuela Militar de Lanceros (The Lancero School) in Colombia is the most-respected Ranger Course in Latin America since its inception in 1956. The Lancero School, like the U.S. Army Ranger School, provides junior officers and enlisted men with the skills and attributes needed to be strong tactical leaders throughout the Colombian Army and in the Lancero Group that does special reconnaissance and direct action missions for the Army divisions. The Lancero badge is a mark of distinction worn by military leaders throughout the Americas.

The purpose of this article is to explain why and how two U.S. Army Ranger officers, initially on temporary duty (TDY), developed the Lancero training program for the Colombian Army in the mid-1950s. That initiative between Colombia and the United States resulted in one of the longest one-on-one professional military relationships. It ranks in the top three (duration) Military Professional Exchange Programs (short term PEP Program) in the U.S. Army, and has done more to instill professionalism in the Colombian Army than has any security assistance program. However, even the “can-do” Captain Ralph Puckett Jr. was not sure that he could get a Ranger course “off the ground” after his first six months in Colombia.1

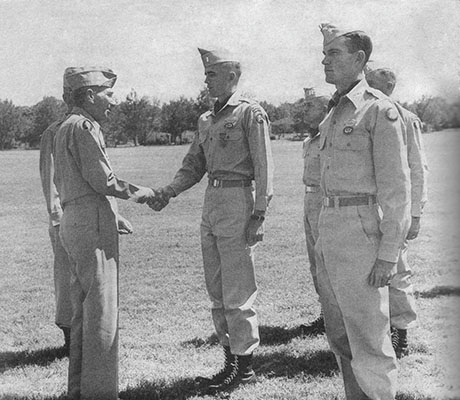

As a Second and First Lieutenant, Ralph Puckett, U.S. Military Academy, Class of 1949, recruited, organized, trained, and led the Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) Ranger Company in combat. It was the first Ranger Company to fight in the Korean War. Lieutenant Puckett was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroic actions against the Chinese on 25–26 November 1950. After his combat tour Captain Puckett served in all phases of the Ranger Training Program at Fort Benning, Georgia, and the Mountain (Dahlonega, Georgia) and Florida (Eglin Air Force Base) Camps. These assignments prepared him for duties in the 65th Infantry Regimental Combat Team (RCT) in Puerto Rico, and his subsequent mission to establish a “Ranger” training program in Colombia in 1955.2

The 65th Infantry officers, NCOs, and soldiers of the traditionally Puerto Rican unit were being integrated into units throughout the U.S. Army in the post–Korean War days. The regiment was also losing some outstanding, combat-experienced NCOs and soldiers as the Puerto Rican “insulares” were replaced by U.S. soldiers referred to as “continentales.” The 65th Regimental commander ordered Puckett to establish two training programs to prevent degradation of combat readiness. One was an Orientation School [basic combat training (BCT) refresher course] for incoming privates and privates first class. The other was an NCO Academy. The Academy’s five-week course, which Puckett patterned after the Ranger School, was designed to prepare soldiers to become NCOs and improve the skills and leadership of junior NCOs.3

At the same time, the Colombian Army generals were selecting five lieutenants to attend airborne training and Ranger School at the U.S. Army Infantry School at Fort Benning and the U.S. Army Mission in Bogotá was requesting an American Ranger–qualified officer for a six-month temporary duty (TDY) assignment to Colombia. Puckett was selected for the assignment shortly after the first class graduated from the NCO Academy.4

On the way to Colombia, Puckett spent a few days at the U.S. Army Caribbean Jungle Warfare Training Center in Panama. He needed to establish rapport, explain his mission, assess requirements for suitable training areas, collect relevant lesson plans, and the current program of instruction (POI).5 Since no U.S. Army School of the Americas existed, all training material was in English and Spanish-English military dictionaries simply did not exist.

Colonel Robert G. Turner, the U.S. Army Mission commander, had recently been Director of the Weapons Department at the Infantry School. Turner explained the mission to CPT Puckett. According to the Colombian president, Lieutenant General (LTG) Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, Ranger training was “to develop to the maximum, by practical field training, the potential for military command and leadership of selected company-grade officers and noncommissioned officers throughout the Army in order to improve the leadership and training capabilities of all units.”6

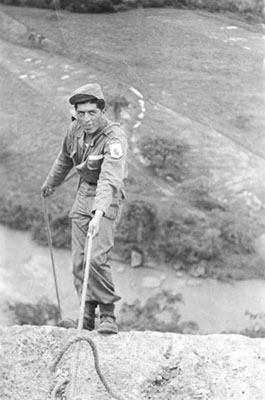

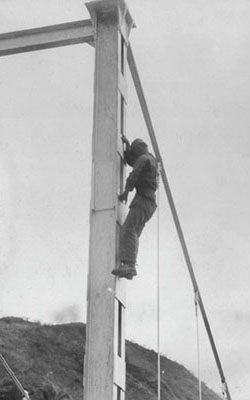

“He did that in ten minutes. Then, Turner said, ‘Get to work.’ The Colombian officers that were to help me were months away from finishing Ranger School. Nothing was mentioned about a training site. That’s when I realized that once again it was up to me to make it happen … much like the EUSA Ranger Company mission in Korea,” recalled Puckett. “It quickly became apparent that logistical support was going to be a problem. Although the president, General Rojas Pinilla, was enthusiastic about the training, the senior Army leaders at the time were not. A twelve-week POI [six weeks of individual Ranger tactical skills training followed by six weeks of unit training in the mountains and jungle (three weeks of each)] was whittled down to eleven weeks. But, the real challenge was a training site. A U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Mathew Santino and I spent several weeks roaming the country to look at possible locations for the new school.”7

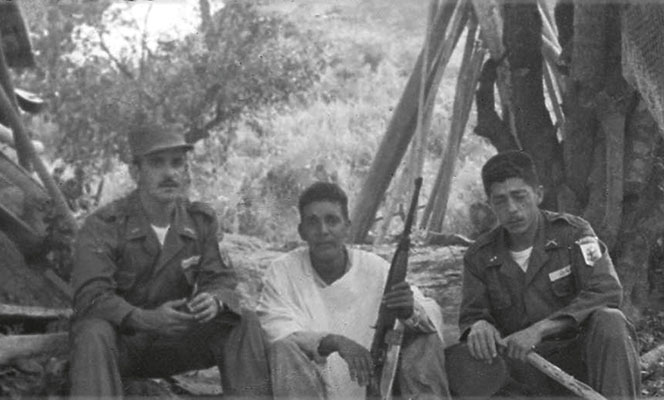

General Rojas Pinilla ultimately decided on a flat bluff above Melgar, on the Río Sumapaz, about a hundred and twenty kilometers south of Bogotá. He was familiar with the area because his family had a coffee finca (plantation) nearby. In 1958, the Batallón Colombia (veterans of Korea) relocated from Bogotá to the new base being established at Tolemaida. The commander of the Colombian Army Schools Brigade, Brigadier General (BG) Rafael Navas Pardo, selected Major Hernando Bernal to command their Ranger School. This was unusual because all other military schools were headed by colonels at the time. Colonel Turner, the Army Mission commander, realized the significance of this maneuver. The Army was putting the onus for getting the school “up and running” on the Americans, namely CPT Puckett. While it was a priority for the president, General Rojas Pinilla, it was not for a Colombian Army that consisted of only eight to ten battalions at the time. Hence, one of the five Colombian lieutenants selected for parachute training and Ranger School at Fort Benning to cadre the new school was “milked off” by Lieutenant General Pedro A. Muñoz, Colombian Army commander, to serve as his aide-de-camp. By then, Puckett was already into his second six months of TDY in Colombia.

Once the training site was fixed, CPT Puckett compiled a list of equipment needed. “It had everything from machine guns to toilet paper. We had literally nothing. I went to the Army Mission in Bogotá every week to ‘beg, borrow, and steal’ necessities—and to insure that the U.S. Military Advisory Assistance Group (MAAG Colombia) requisitioned equipment from the U.S. Army in the Canal Zone and to solicit support from the Colombian Army,” remembered Puckett. “When the four Ranger-qualified Colombian lieutenants arrived, our focus became the development of the POI, lesson plans, training sites, field exercise objectives, rehearsals—all those things required to set up a school from nothing. I cannot say that we concentrated on one thing. Impossible as it sounds, we focused on everything. In the midst of the frenzy to get the school established attitudes changed,” recalled Puckett.8