DOWNLOAD

The 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) provides rotary wing (helicopter) aviation support to today’s Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF). The “Night Stalkers” are the premier practitioners of long-range, low-level night operations. During the Vietnam War, the 129th Assault Helicopter Company performed missions similar to those associated with modern SOF aviation. Inactivated in the years after the Vietnam War, the 129th was resurrected during the formative years of the 160th SOAR.1

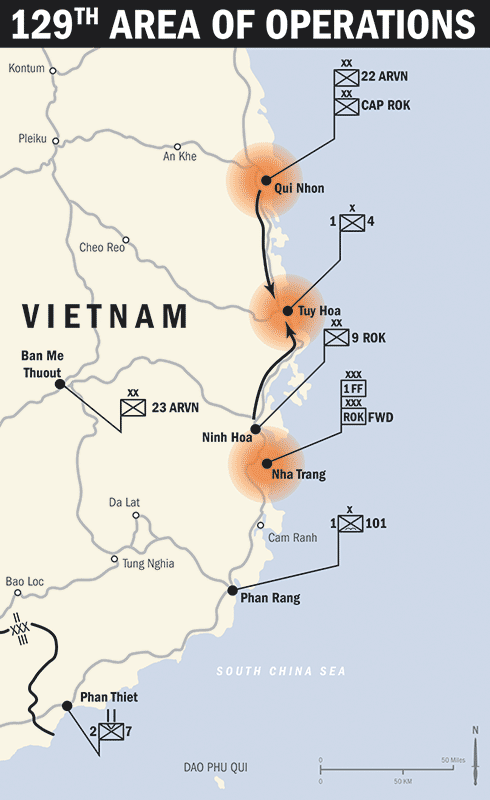

The 129th Assault Helicopter Company was formed on 3 July 1965 and activated on 5 July 1965 at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. The unit deployed to Vietnam where it served from 21 October 1965 to 8 March 1973. The company was assigned to the 10th Aviation Battalion, part of the 17th Aviation Group. An Assault Helicopter Company, the principal mission of the 129th was the tactical air movement of troops and equipment within the area of operations. In conjunction with this mission, armed helicopters provided suppressive fire support to protect the insertion of troops. The organization of the company reflected these two missions.

When the unit arrived in Vietnam, it was organized into four platoons. Two of the platoons were “lift platoons” flying Bell UH-1D “Huey” helicopters. (In 1968 the unit received newer “H” model Hueys). Called “Slicks” because the cargo area of the helicopter was devoid of seats or other equipment to facilitate carrying troops and cargo, these two platoons formed the “Bulldog” element of the company. Supporting the two lift platoons was one armed platoon, nicknamed the “Cobras,” flying the UH-1B model “Hog” Hueys. (Later in the war, Bell fielded the AH-1 Cobra model attack helicopter, a two-man gunship.)2 The fourth platoon in the company was the service platoon that included the aviation maintenance, supply, and mess teams.

After a year in Vietnam, the company reorganized into a five-platoon configuration by adding a third lift platoon as well as the 394th Aircraft Maintenance Transportation Detachment and the 433rd Medical Detachment (Air Ambulance) for additional maintenance and medical capability.3 The average strength of the company was 15 officers, 52 warrant officers, and 152 enlisted men. The two flying elements, the “Bulldogs” and “Cobras,” were the reason behind the company motto “Bite and Strike.” The unit compiled an impressive record during the eight years it was in Vietnam.