DOWNLOAD

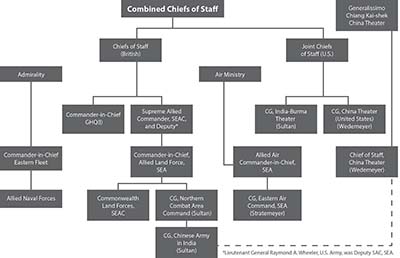

OSS operations in Thailand and Southeast Asia are less well known than the activities of the OSS in Burma (Detachment 101) and China (Detachment 202). However, the activities of Detachment 404 in Thailand were politically important to setting the stage for U.S. foreign policy in Southeast Asia during the Cold War. To appreciate the contributions of Detachment 404 that promulgated the post-war relationship with the government of Thailand, it is necessary to explain the complex command relationships that affected the OSS in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater of operations. Early in the war, the Pacific commanders, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and General Douglas MacArthur, barred the OSS from their areas of operation. It was Lieutenant General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell’s CBI Theater that provided the OSS its only entrance into Asia.

One of the results of the Quebec Conference in September 1943 was the creation of a separate Allied Command for Southeast Asia (SEAC). Quebec was the site of one of several strategic planning conferences conducted during the war. There, the political and military leadership of the Allied nations met face-to-face to discuss war strategy. British Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten was named the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia (SEAC). LTG Stilwell, U.S. commander in the CBI theater, became the deputy supreme commander. SEAC was created to bring some unity and new energy to a theater comprised of distinct countries (India, Burma, China) with often competing Allied and U.S. service interests.1

In November 1943, Major General William J. Donovan, the head of the OSS, met with Lord Mountbatten in New Delhi, India, to discuss expanding OSS operations in Southeast Asia. The agreement reached between Donovan and Mountbatten resulted in a reorganization of the OSS in Asia. At that time, Detachment 101 and various OSS headquarters and liaison personnel were focused on the China and Burma theater. Donovan conceded a change of authority for OSS activities from the U.S. theater commander, LTG Stilwell, to “P” Division of the SEAC headquarters. “P” Division, headed by a Royal Navy captain with an American deputy, was the staff section responsible for all clandestine activity in the theater (espionage, sabotage, propaganda, etc.). In return, Detachment 101 retained its tactical autonomy as an allied guerrilla force operating in northern Burma. It was essentially exempt from SEAC operational oversight. They also agreed that the OSS could only provide U.S. intelligence directly to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington instead of routing it through SEAC headquarters to the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff in London.2