Following the 11 September 2001 terrorist attack that destroyed the World Trade Center, the United States targeted the Islamic-fundamentalist Taliban regime in Afghanistan which had taken over the country and provided support and refuge to the al-Qaeda terrorists. Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) spearheaded the ground campaign of Operation ENDURING FREEDOM (OEF) that began in November 2001 and, by May 2002, drove the Taliban from power. Joint Special Operations Task Force–North (JSOTF-North) known as Task Force Dagger (TF Dagger) was formed around the 5th Special Forces Group (SFG) to conduct the campaign in the northern half of Afghanistan.1 The logistical support to TF Dagger was provided by Logistics Task Force 530 (LTF 530). The focus of this article is the preparation and execution of the logistical support mission for TF Dagger as performed by the men and women of LTF 530.

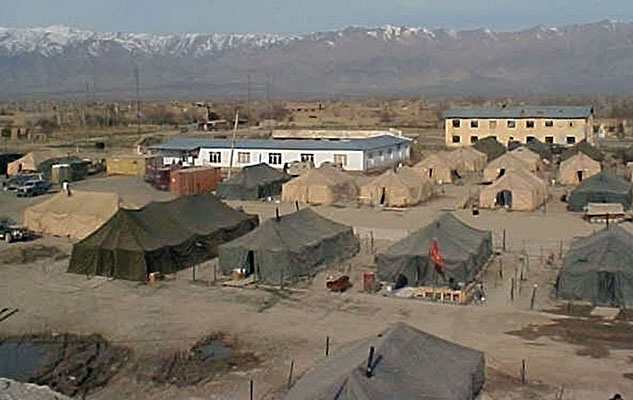

The American forces could not stage directly into Afghanistan to begin operations against the Taliban. For the conduct of combat operations in the north, the U.S. forces established Camp Stronghold Freedom at the Karshi-Kanabad Air Base in Uzbekistan. Known as K2, the airfield became the operational and logistics center for TF Dagger beginning with the arrival of the advanced echelon (ADVON) on 6 October 2001.2 K2, just across the northern Afghan border, quickly grew as troops and equipment flowed in.

Logistical support to ARSOF units within the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) was the responsibility of the 528th Special Operations Support Battalion (SOSB).3 A Company, 528th SOSB, commanded by Captain Christopher Mohan, established the initial base and logistics operations at K2 and supported the build-up of forces in October and November. The long-range plan for support operations called for the deployment of the logistics task force into K2 to take over operations from the 528th, and to be prepared to move into Afghanistan to provide logistical support to JSOTF-North in the northern half of the country. The deployment of the logisticians began on 15 November 2001, and as LTF personnel arrived, they assumed the K2 mission.

Lieutenant Colonel Edward F. Dorman commanded LTF 530, which was task organized from assets of the 530th Supply and Services Battalion (S&S), of the 507th Corps Support Group (CSG), in the 1st Corps Support Command (COSCOM) at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. From the 530th S&S came the 530th Headquarters and Supply Company (HSC) commanded by Captain Mathew Hamilton. The 58th Maintenance Company (General Support), 7th Transportation Battalion, 507th CSG led by Captain Judy Anthony formed the other half of the task force. The two companies, with augmentation, provided the entire range of logistical support.

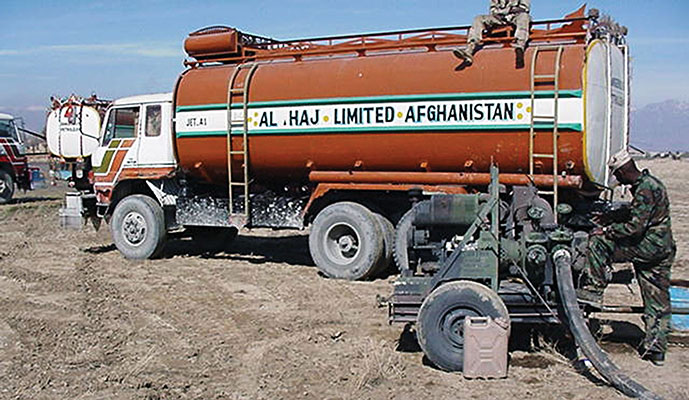

Headquarters and Support Company’s mission was to provide for the reception and distribution of most of the basic classes of Army supply: Class I (subsistence/rations), Class II (clothing and equipment), Class III (petroleum products), Class IV (construction materials), Class V (ammunition), Class VI (personal demand items such as toiletries), Class VII (major end items such as vehicles and weapons), Class VIII (medical supplies), and Class IX (repair parts). The production and distribution of potable water and provision of general support services such as billeting, food service, laundry and bath facilities, and sanitation were also part of the company mission. The 530th HSC ran the Airfield Departure and Arrival Control Group (ADACG) that coordinated the flights in and out of K2 as well as managed the Humanitarian Assistance (HA) commodities flowing in.4 HSC had seventy-nine soldiers to accomplish these many and varied tasks.5 In a simplistic way, HSC took care of the troops on the ground while the 58th Maintenance Company took care of the equipment.