SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

The Montagnard Uprising of 1964, was a complex event with the potential to alter the course of the Vietnam War. The one constant during this political and military maelstrom was the efforts of Special Forces soldiers, noncommissioned officers and officers, that defused the situation. The eight-day Montagnard uprising was just a “blink of an eye” in the fifteen years of American involvement in Vietnam, but had a lasting impact. This event will be explained from the perspective of a single Special Forces team.

American Special Forces (SF) teams built a close relationship with the Montagnards in the Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) program in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Suddenly, on Sunday, 20 September 1964, the American soldiers were jolted into a new reality when the friendly “Yards” revolted against the Vietnamese government. The U.S. Special Forces soldiers watched in horror as their trusted allies killed or imprisoned their Vietnamese Special Forces “commanders” and other Vietnamese present in four CIDG camps. In some camps, the Montagnards imprisoned the American SF teams. However, in one camp, Buon Brieng, the teamwork, quick response, and resourceful actions of one A-Team prevented a takeover; the Americans remained in control, and ultimately defused the uprising.

This article features Special Forces Team A-312, 1st Special Forces Group (1st SFG), based in Okinawa, Japan. Sent to train, advise, and lead Montagnard irregular soldiers against the Viet Cong in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam, A-312’s experience typified that of many other SF teams in Vietnam in 1964. Although this article centers on Team A-312, it also encapsulates the early role of SF in the CIDG program in Vietnam.1

In the Central Highlands, the Special Forces and CIDG fought two groups, the Viet Cong (VC) and the Viet Montagnard Cong (VMC). The VC were ethnic Vietnamese who traced their lineage to the Viet Minh, the communist movement that fought the Japanese and then the French for Indochinese independence. The VMC were ethnic Montagnards who worked with VC units in the region. While the Viet Cong had pressed many Montagnards into service, others were trained as a political cadre by the communists to organize the Montagnards to fight against the Vietnamese government. Their targets in the Central Highlands were the American-supported CIDG camps.2

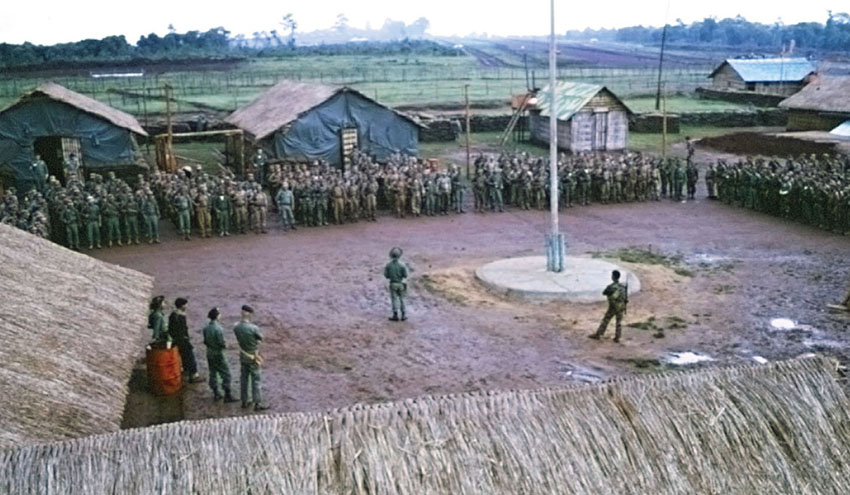

Five CIDG camps surrounded Ban Me Thuot. They were organized as light infantry battalions. Depending on recruitment, the Strike Force battalions varied in strength. Buon Brieng had the largest force, with five companies. The other four camps had between three and four companies. Each Strike Force company was organized as a light infantry company with a small headquarters and four platoons of thirty Montagnards armed with surplus World War II weapons.3 American Special Forces teams advised the CIDG units in conjunction with their Vietnamese SF counterparts.

Officially, Lực Lượng Đặc Biệt (LLDB, the Vietnamese Special Forces) teams were in charge of the CIDG at each camp. American SF were only there to advise the Montagnards, but in reality, they commanded and led the CIDG companies. The LLDB were content with this arrangement and rarely left camp. Every camp had an assigned area of responsibility. The belief was that as more camps were established and patrols expanded, the Viet Cong would be driven out of the area.4 The Montagnards were the key element of the CIDG program, but they also hated the Vietnamese because they had “invaded” their territory.

In many of the CIDG camps throughout Vietnam, a strained relationship existed between the Montagnards and the Vietnamese Special Forces (LLDB). When Captain Gary A. Webb and Team A-311B arrived at Bu Prang on 27 August 1964, they discovered a major problem. The LLDB were “in cahoots with the merchants in the ‘ville’ [village] to cheat the troops,” and “instead of paying the troops, [the Montagnards] were given credit in the ‘ville’ for food, clothes, wine, or whatever at a particular shop … and the bill was sent to the LLDB Finance Officer or NCO. The individual’s account was debited by the amount he owed in the ‘ville’,” recalled Gary Webb.5 The scam enabled the LLDB and the ARVN (Army of South Vietnam) Camp commander to pocket part of the CIDG payroll. The American SF invariably found themselves in the middle between the Vietnamese and the Montagnards.

The Montagnard uprising of September 1964 did not occur in a vacuum. The spring and summer of 1964 was filled with “political conspiracies; attempted military coups; and Buddhist, Catholic, student, and labor demonstrations and protests.”6 At the end of the summer, General Nguyen Khanh seized power, by coup, in Saigon.7 The uprising cannot be written off as a mutiny against South Vietnamese authority and the traditional oppression of the Montagnards. It was a combination of both during a turbulent period. The center of the Montagnard population was in the II Corps area of operations around the city of Ban Me Thuot, the traditional Montagnard capital.

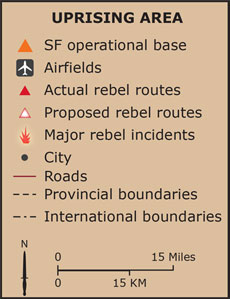

The Montagnard organization, “Fronte Unifié Pour La Libération des Races Opprimées” (United Front for the Liberation of the Oppressed Races—FULRO) planned the uprising against the South Vietnamese government. It would take place in the Ban Me Thuot area of the Central Highlands in Darlac province. When Ban Me Thuot became predominately Vietnamese in population, the Montagnards migrated deeper into the highland regions. The mountains surrounding the city were filled with villages of traditional Montagnard longhouses. According to the FULRO uprising plan, the Montagnard strikers would seize the central five CIDG camps in the II Corps Tactical Zone (Buon Mi Ga, Bon Sar Pa, Bu Prang, Ban Don, and Buon Brieng). This would start the eight-day open rebellion against the South Vietnamese government.8

The second phase of the FULRO plan called for the strikers from all five camps to seize and secure control of Ban Me Thuot. The Montagnards would leave a nominal security force at each camp, while the majority of the units established blocking positions on the roads to Ban Me Thuot or moved into position to seize the city. Once the city was secured, the FULRO leadership planned to negotiate with the Vietnamese government to regain the political autonomy enjoyed under the French. Although it was a loose coalition/confederation, every camp was critical to the success of the uprising.9

During the night and early morning of 19–20 September 1964, the Montagnard CIDG troops in all five camps executed—without warning—the well planned phase I of the uprising. At four camps (Buon Mi Ga, Bon Sar Pa, Bu Prang, and Ban Don), the Montagnards disarmed and restricted their U.S. Special Forces advisers to their billets. In the fifth, Buon Brieng, the Strike Force did not harm the Vietnamese nor disarm the Americans.10 Because of the events at Buon Brieng and the proactive measures taken by the Special Forces there, the overall uprising failed.

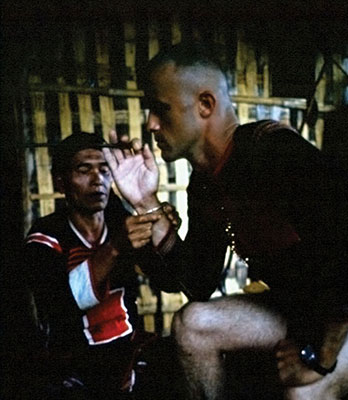

In September, Team A-312 was over halfway through its six-month TDY tour in Vietnam that had begun in June 1964. “Typical” of many Special Forces A Teams in Vietnam, A-312 recruited, trained, led into combat, and suffered casualties with their Montagnard irregulars. Aggressive patrolling led to the team’s first casualty. On 23 July 1964, Specialist Fourth Class George Underwood, the junior medic, was killed in a VC battalion-sized ambush while leading a resupply convoy back from Ban Me Thuot. Specialist Fifth Class Ricardo Davis was his replacement from Okinawa. “In the Rhade tribe, men’s names began with a ‘Y.’ Since Davis arrived with a buzz cut or ‘burr’ haircut, someone nicknamed him ‘Y-Burr,’” said Sergeant Lowell Stevens. It stuck for several years.11 When Sergeant First Class Billy Akers was transferred to B-52 Delta, a classified reconnaissance project, Sergeant First Class Billy Ingram became the medical sergeant.12 The team continued to execute their mission while incorporating the new members.

A-312 built a strong rapport with the CIDG and the Vietnamese Special Forces. The newly appointed Montagnard battalion commander, Y Jhon Nie, was a product of two worlds; his father was French and his mother Montagnard. His mother had raised him as a Montagnard before being sent to a Catholic boarding school. There he learned French and English. After completing school, he returned to the Montagnards because he was still discriminated against by the lowland Vietnamese. He joined the CIDG and rose rapidly through the ranks as a combat leader. When A-312 arrived at Buon Brieng, in June 1964, he was Sergeant Earl Bleacher’s 3rd Company commander. Y Jhon soon rose to be the battalion commander.13

After three months, the SF of A-312 had bonded closely with their Yards. Buon Brieng was exceptional. The relationship between the Vietnamese and Montagnards was good. That was the case until “leading up to the uprising there was something going on, but we couldn’t put our finger on it. The Montagnards were edgy,” said SGT Bleacher. “Several [of the Montagnards] had asked us the question, ‘If the Vietnamese fought the Montagnards who would you side with?’”14 Team commander, Captain Vernon Gillespie, radioed his concerns to the SF B Team in Pleiku and to SF Headquarters in Nha Trang. The issue was significant enough that he followed the radio messages with coordination visits to Nha Trang and Saigon. However, the Americans had no solid intelligence, “it was just a shadow,“ Gillespie remembered.15 That shadow soon emerged from the darkness on 19 September 1964.

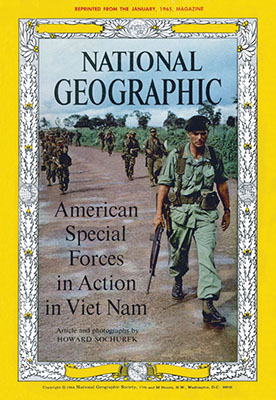

National Geographic cover showing Major Edwin Brooks leading the rebels away from the radio station. The photo was taken by Howard Sochurek.

On 18 September 1964, A-312 received a surprise guest. Howard Sochurek, a World War II combat photographer and career journalist, came to research the Montagnard tribes and write an article for National Geographic magazine. Sochurek proved to be lucky. He was the only American journalist in the area when the uprising started. The first thing the Vietnamese government and Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) did was to restrict all movement into the area, thus keeping the press out. His exclusive story was featured in the January 1965 issue of National Geographic.16 Sochurek was there when it erupted.