DOWNLOAD

A noteworthy aspect of the Korean War was the first combat employment of U.S. Army Special Forces. North Korean partisan units, known as WOLFPACKS and DONKEYS, were advised by Americans as they raided the enemy from islands off both coasts of the Korean Peninsula. Special Forces soldiers from the 10th Special Forces Group advised the partisans and conducted unconventional warfare operations on the mainland.

The Korean War (1950-1953) ended in an armistice with the armies of North Korea and Communist China facing the forces of South Korea, the United States and the other countries of the United Nations coalition across the 38th Parallel. The first year of fast-paced, fluid, conventional combat up and down the Korean peninsula was followed by a gradual stalemate as the armies of both sides hardened their defensive positions and jockeyed for the most advantageous terrain. The armistice agreement of 27 July 1953 brought an end to active combat, but did not end the war. Today the 38th Parallel remains the most heavily defended border in the world.

Unconventional warfare was a feature of combat operations throughout the war, which began when the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) invaded the Republic of Korea in June 1950. The NKPA rapidly overran the south during this first year resulting in a large number of anti-communist North Koreans fleeing their homes in the north and moving into South Korea. A significant percentage of these anti-Communist refugees formed guerrilla bands and fled to the islands off the east and west coasts of Korea near the 38th Parallel. The training and employment of these partisan units became a major part of the U.S. Army unconventional warfare (UW) effort.

The organization and conduct of unconventional warfare in Korea was complex and involved not only the U.S. Army, but the Navy, Air Force, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Republic of Korea as well as the United Nations, and began to take shape before the war started. Formed after World War II, the United States Far East Command (FEC) was responsible for combat operations in Korea. FEC was a joint headquarters operating from the Dai’ichi Building in Tokyo, Japan.1 General Douglas MacArthur commanded FEC and was “triple-hatted” to serve as the Supreme Commander, Allied Powers (SCAP) and as the commander of the U.S. Army Forces, Far East, (USAFFE). His G-2 (Intelligence), Major General Charles A. Willoughby, formed the Korean Liaison Office (KLO) during the interwar period to collect information about North Korea by inserting agents across the border. In June 1950, the KLO was virtually the only U.S. organization collecting intelligence on Kim Il Sung’s Communist government.2

FEC began to develop an unconventional warfare capability in 1950 to take advantage of the large number of North Korean partisans who had settled on the off-shore islands. This led to the formation of the 8240th Army Unit by the Miscellaneous Group of the Guerrilla Section, G-3, Eighth U.S. Army in late 1950.3 The unit went through a series of name changes; starting as the Miscellaneous Group, 8086th Army Unit (AU) on 5 May 1951, and becoming the Far East Command Liaison Detachment Korea (FEC/LD/K), 8240th Army Unit on 10 December 1951.4 After the signing of the armistice, the unit was carried as the 8007th Army Unit and in September, 1953 it became the 8112th Army Unit.5 These changes were made for security reasons. There was no significant alteration in the unit’s mission. The 8240th was the Eighth U.S. Army’s unit responsible for employing the partisans in an unconventional warfare role.

The build-up of the 8240th AU occurred concurrently with a steady increase in unconventional warfare activities conducted by the CIA, the UN Command, the ROK Army, the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force. Within HQ FEC was a special staff section called the Documents Research Division headed by a representative of the CIA. The Joint Advisory Commission Korea (JACK) managed the CIA operations in Korea and the deputy commander, Major (MAJ) John K. Singlaub, was a military officer attached to the CIA.6 In an attempt to get a handle on theater unconventional warfare operations and eliminate duplication, HQ FEC had created the Combined Command for Reconnaissance Activities Korea (CCRAK) under the staff supervision of the G-2.7

Directed by Brigadier General Archibald Stuart, whose deputy was from the CIA, CCRAK’s mission was to deconflict the various unconventional warfare operations run by the different commands and organizations in Korea.8 CCRAK was a coordinating headquarters and had no command authority over JACK or the other elements engaged in UW activities. MAJ Singlaub, the Army officer detailed to be the deputy of JACK noted that “JACK had neither the responsibility nor the inclination to coordinate its independent covert activities with CCRAK.”9 Consequently CCRAK only exerted minimal influence by controlling FEC aviation and maritime assets essential to the units conducting UW operations. The number of organizations engaged in unconventional warfare activities required constant coordination by the 8240th. MAJ Richard M. Ripley, commander of the 8240th’s WOLFPACK guerrilla group remembers; “There was a period when people were working on top of each other. I counted 15 or more different U.S. and Allied organizations working in our area.”10 In most cases, the different organizations had missions similar to those of the 8240th.

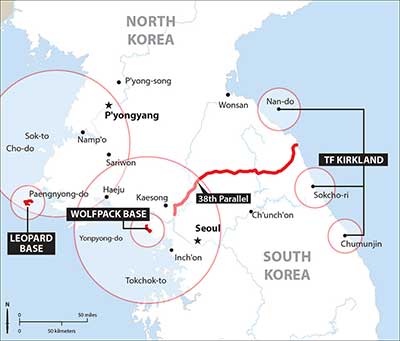

The mission of the 8240th, as defined in the unit Table of Distribution (TD), was twofold. First; “to develop and direct partisan warfare by training in sabotage indigenous groups and individuals both within Allied lines and behind enemy lines,” and second; “to supply partisan groups and agents operating behind enemy lines by means of water and air transportation.”11 To accomplish these missions, the 8240th established four sections between 1951 and 1952. Three sections controlled guerrilla operations, WOLFPACK, LEOPARD, and TASK FORCE (TF) KIRKLAND. Geography determined the location of these sections. The fourth, BAKER SECTION, provided aerial resupply, airborne training, and inserted agents using C-46s and C-47s. Aviation support for the 8240th was the responsibility of the AVIARY team of BAKER SECTION, located at the ROK Ranger Training School at Kijang near Pusan. BAKER SECTION later moved to the K-16 Airfield outside Seoul.12

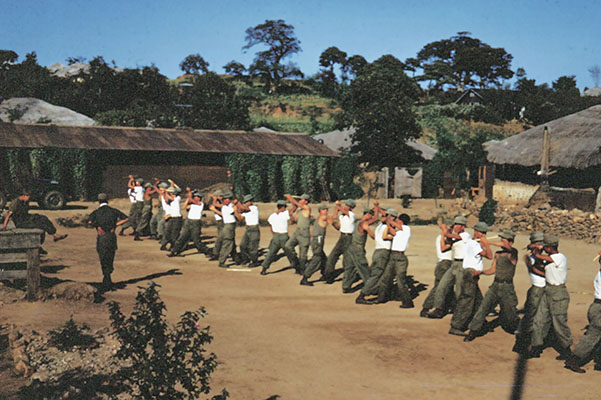

On the west coast, LEOPARD, originally called WILLIAM ABLE BASE, was located on Paengnyŏng-do. Formed in February 1951, it supported roughly 12,000 men organized into 15 units called DONKEYS. The origin of the term “DONKEY” is uncertain. It is sometimes said to be a derivation of the Korean term dong-il (leader). It was adopted soon after Colonel John McGee took command of the 8240th in early 1951 and may have come from a speech McGee gave to the guerrillas telling them to follow the example of the “wise mule” in avoiding confrontations. Wise mule became donkey in translation.13 The LEOPARD area of operations was generally north of the 38th Parallel to the west of the Ongjin Peninsula, reaching as far north as Taehwa-do at the mouth of the Yalu River on the Chinese border.14 Eight DONKEYS were located on Cho-do and the remaining seven on other islands. LEOPARD was organized a year before WOLFPACK.

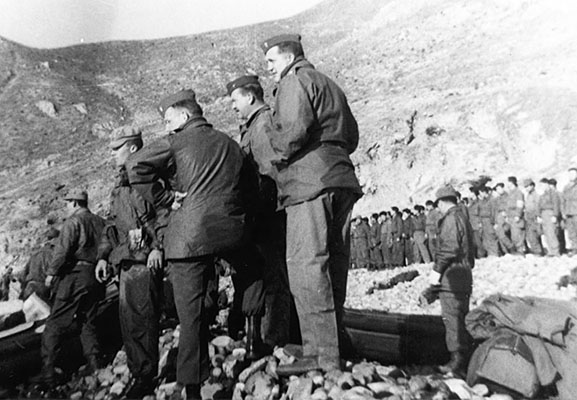

Established in January 1952, WOLFPACK was composed of eight units initially totaling 3,800 partisans.15 The units were called WOLFPACK 1 thru 8. They occupied various islands south of the 38th Parallel on the west coast. WOLFPACK headquarters was on the large island of Kangwha-do due west of Seoul, with the units on adjacent islands. WOLFPACK conducted operations behind enemy lines in the southern portion of the Ongjin Peninsula northwest of Seoul.16 Major Richard M. Ripley commanded WOLFPACK in the spring of 1952. “Our mission was to harass and interdict the rear areas. We conducted raids and ambushes and laid mines along the MSRs [Main Supply Routes].”17 By late 1952, the LEOPARD unit reported a strength of 5,500 partisans and WOLFPACK, 6,800.18 A compilation of the two unit operational reports for the week of 15-21 November 1952 recorded 63 raids and 25 patrols against the North Korean coast resulting in an estimated 1,382 enemy casualties.19 By official policy, Americans were prohibited from accompanying the partisans on their missions. Thus the numbers associated with enemy casualties were inaccurate. The robust partisan forces on the west coast were difficult to control and supply. This later resulted in the 8240th initiating an organizational change. Partisan operations on the east coast were the responsibility of TF KIRKLAND.

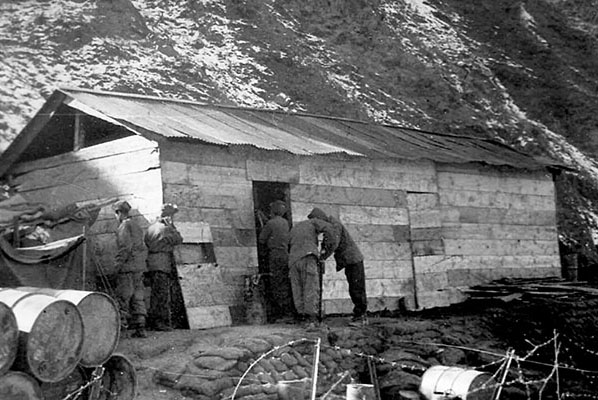

TF KIRKLAND was the smallest of the three partisan commands, comprising five units and 6,000 troops. Based on the mainland 40 miles south of the 38th Parallel in the eastern coastal village of Chumunjin was the TF KIRKLAND headquarters and the sub-unit called AVANLEE. Twenty miles up the coast to the north in the village of Sokcho-ri were two other elements, STORM and TORCHLIGHT. Further north on the island of Nan-do was the TF Forward Command Post with partisan forces on some of the surrounding islands.20 TF KIRKLAND conducted amphibious insertions of agents and raids along the east coast between the 38th Parallel and the North Korean port city of Wonsan.21

Initially, Eighth Army manned the 8240th with U.S. Army volunteers from within the theater. Colonel John McGee, the original head of the Miscellaneous Group was the first commander of the 8240th in Taegu. He industriously recruited veterans to serve as advisors to the partisans on the islands. When the five numbered Ranger companies and the Eighth U.S. Army Rangers were disbanded on 1 August 1951, the men were distributed among the American infantry divisions and the 8240th.22 First Lieutenant (1LT) Joseph Ulatoski, the former Executive Officer of the 5th Ranger Company, joined the 8240th and was assigned to TF KIRKLAND.

“I’d just been released from the Swedish Red Cross hospital and my friend Phil Lewis from the 7th Ranger Company signed me up for the 8086th [later the 8240th]. After a month as assistant G-2, I was sent up to Sokcho-ri and then out to one of the islands.”23 The island, Song-do, near the TF KIRKLAND forward base on Nan-do, lay 700 yards off the mainland. Arriving on a motorized sampan, Ulatoski found a tent city and three different groups of partisans on the island.

“We had no real briefing or training to prepare for this. It was one hundred per cent ‘fly by the seat of your pants.’ There were three groups on the island including the East Coast Patriotic Volunteers, under a Major Han. I had a corporal, Cyril Tritz from the 4th Ranger Company, with me and we began to collect intelligence as well as gather food, weapons and communications gear.”24 Located so close to the mainland, the island was not immune to North Korean attacks.

“We got hit a couple of times, just probes, no major attacks. The partisans were not the most observant group of people and during the raids we Americans took up a position away from the action to avoid getting shot up by either side.”25 1LT Ulatoski served on the islands for ten months, during which time he noted “there was no command and control capability with the partisans. These North Koreans were strangers to the area and there was no vetting of them. Still, we managed to keep up the insertions of the five or six-man teams. We were able to supply the Navy with [gunfire] targets, probably our best contribution.”26 The experience of 1LT Ulatoski with TASK FORCE KIRKLAND mirrored that of other officers serving with WOLFPACK and LEOPARD on the west coast.