NOTE

*In keeping with USSOCOM Policy, Special Operations soldiers Major and below and the named operational objectives in this article have been given pseudonyms, designated with an asterick (*).

The “Gateway to Kandahar” the Panjwayi Valley is one of the most fertile and productive regions in Afghanistan. Beginning 35 kilometers southwest of the ancient provincial capital city of Kandahar, the Panjwayi extends roughly 50 kilometers south and west almost to the border of Helmand Province. Watered by the Arghandab River, the well-populated valley produces grapes, corn and other crops. It was also a traditional Taliban stronghold. The 1st Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group (SFG) returned to the heartland of the Taliban for a third time in December 2006 as part of Operation BAAZ TSUKA.

Task Force 31 (TF-31), the “Desert Eagles,” as part of the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-Afghanistan (CJSOTF-A), had spent months in the Panjwayi Valley. They had driven the Taliban out of the area during Operation MEDUSA in September 2006.1 But NATO/ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) had failed to maintain a viable presence in the area afterward. The political constraints on combat operations imposed on the different NATO nations by their governments precluded ISAF from developing a coordinated strategy to retain control of the Panjwayi Valley. The Taliban returned in strength just weeks after the end of MEDUSA. By the end of November, the Taliban strength in the valley was estimated to be nearly 800 fighters.2 In December 2006, ISAF launched Operation BAAZ TSUKA (Pashtun for “Eagle Summit”) with the goal of once again driving out the Taliban and delivering essential development assistance to the local populace.3 In the intervening three months between MEDUSA and BAAZ TSUKA, the operating situation of TF-31 had undergone some significant changes.

The purpose of this article is to document the campaign and to highlight the counterinsurgency (COIN) model employed by TF-31 during the operation. Operation BAAZ TSUKA is an example of a successful COIN operation conducted as part of a multi-national operation and is relevant as a blueprint for future operations. This article will examine the situation in the Panjwayi Valley, the missions of ISAF and TF-31, and the scheme of maneuver and execution of Operation BAAZ TSUKA by the “Desert Eagles.”

COL Christopher K. Haas, the 3rd SFG commander was in charge of the CJSOTF. A multi-national command, CJSOTF-A is comprised of special operations forces from twelve countries, including Canada, Great Britain, and the United Arab Emirates. It was responsible for coordinating SOF operations throughout Afghanistan. ISAF is composed of the headquarters, an Air Task Force, five Regional Commands, (RCs), 25 Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRT) and Forward Support Bases throughout Afghanistan with 40 countries contributing forces.4 The mission of ISAF was to bring security, stability, and foster development in Afghanistan.5

The five geographically oriented Regional Commands (RCs) coordinated all civil-military activities conducted by the military elements or PRTs in their respective areas of responsibility.6 TF-31 worked for RC-South, whose area of responsibility encompassed Oruzgan, Zabol, Kandahar, Helmand, and Nimruz provinces. After MEDUSA, Canadian Brigadier General David A. Fraser was replaced by Dutch Major General Ton van Loon on 1 November 2006. A peacekeeping veteran, Major General van Loon commanded a Dutch task force in Bosnia in the 1990’s. These peacekeeping experiences initially made van Loon hesitant to get involved in major combat operations.

In Bosnia, the Croatian, Serbian, and Bosnian elements were separated into discrete ethnic enclaves that helped the NATO peacekeeping forces keep the warring factions apart. Humanitarian aid (HA) could be provided to all groups in relatively secure environments. Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Donald C. Bolduc, the commander of TF-31, worked diligently to convince MG van Loon that solving the problems in southern Afghanistan involved a balance of combat operations and HA. “One of the biggest obstacles was to convince MG van Loon that there could be no development without security,” said LTC Bolduc. “An active insurgency will not allow support to the locals. We needed to balance kinetic and non-kinetic [combat vs non-combat] operations in an intelligence-driven, full-spectrum campaign. It took about thirty days for him to realize this.”7 With van Loon’s support, the staff of TF-31 planned to conquer the valley again.

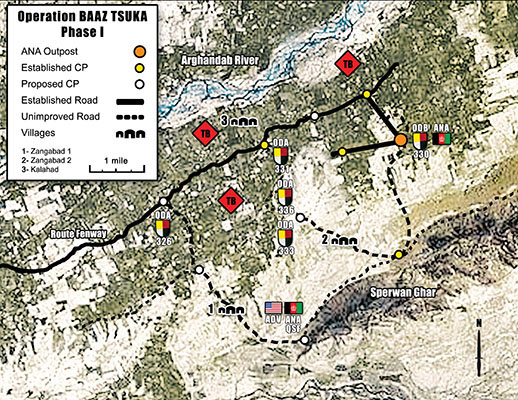

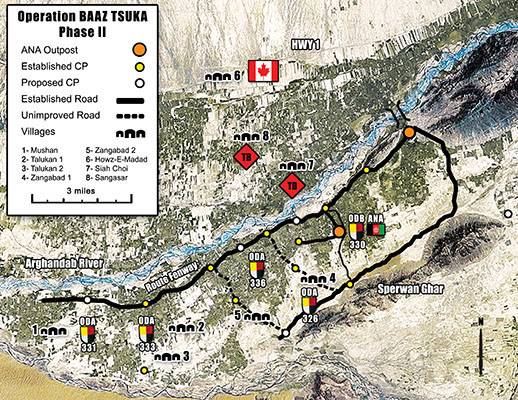

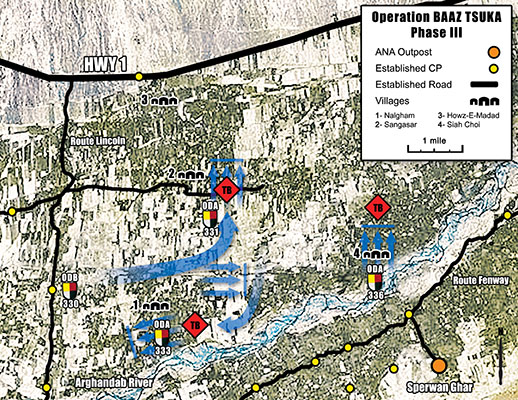

Operation BAAZ TSUKA was a two-phased campaign designed to achieve three important objectives. In Phase I, U.S. and Canadian forces in concert with Afghan National Army (ANA) units would assault from east to west to secure villages in the valley. The Canadians would move down Highway 1 to secure the town of Howz-E-Madad, north of the Arghandab River, and the U.S. forces would take the towns of Zangabad and Talukan on the south side.8 In Phase II, the Canadians would clear the villages of Siah Choi, Nalgham, and Sangasar. Then a company of Dutch infantry, assisted by the U.S. forces, would conduct an airmobile insertion to secure the town of Mushan at the western end of the Panjwayi Valley.9 In both phases, the ANA companies would constitute the bulk of the forces.