NOTE

The WWII abbreviation for prisoner of war was PW. That period acronym will be used throughout this article.

DOWNLOAD

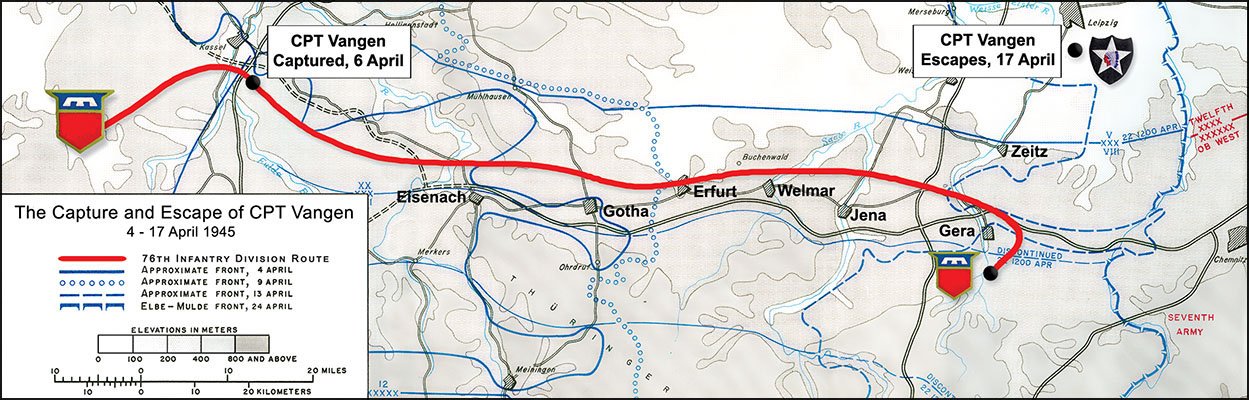

Infantry Captain Terrance A. “Terry” Vangen’s position in World War II was altered dramatically on 6 April 1945. After a string of successes leading his company against the concrete bunkers of the Siegfried Line near Trier, crossing the Rhine, and driving the Germans from a number of towns south of Kassel, his luck abruptly changed. While his E Company, 385th Infantry troops ferreted out enemy soldiers from homes and searched for weapons, CPT Vangen led a jeep reconnaissance of his next objective several miles away.

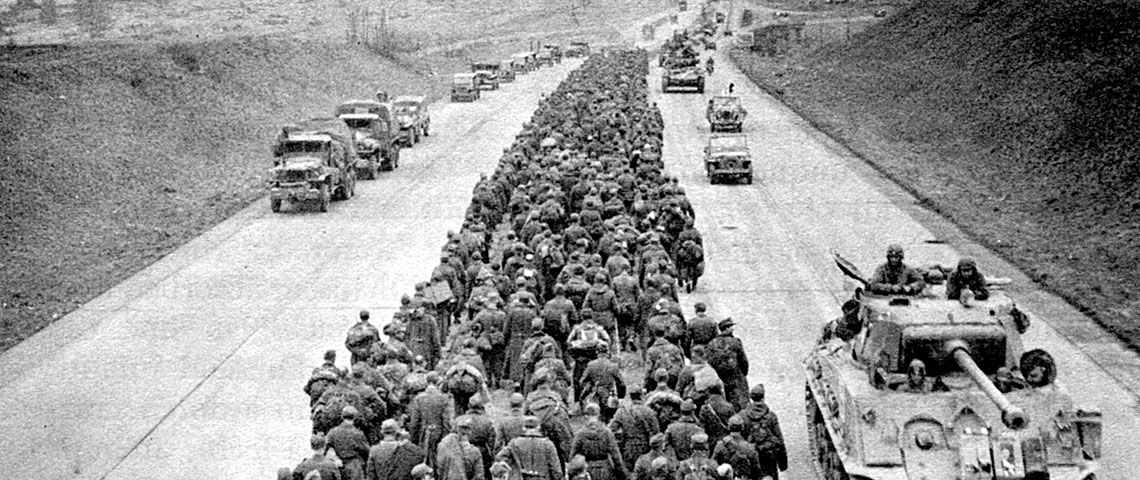

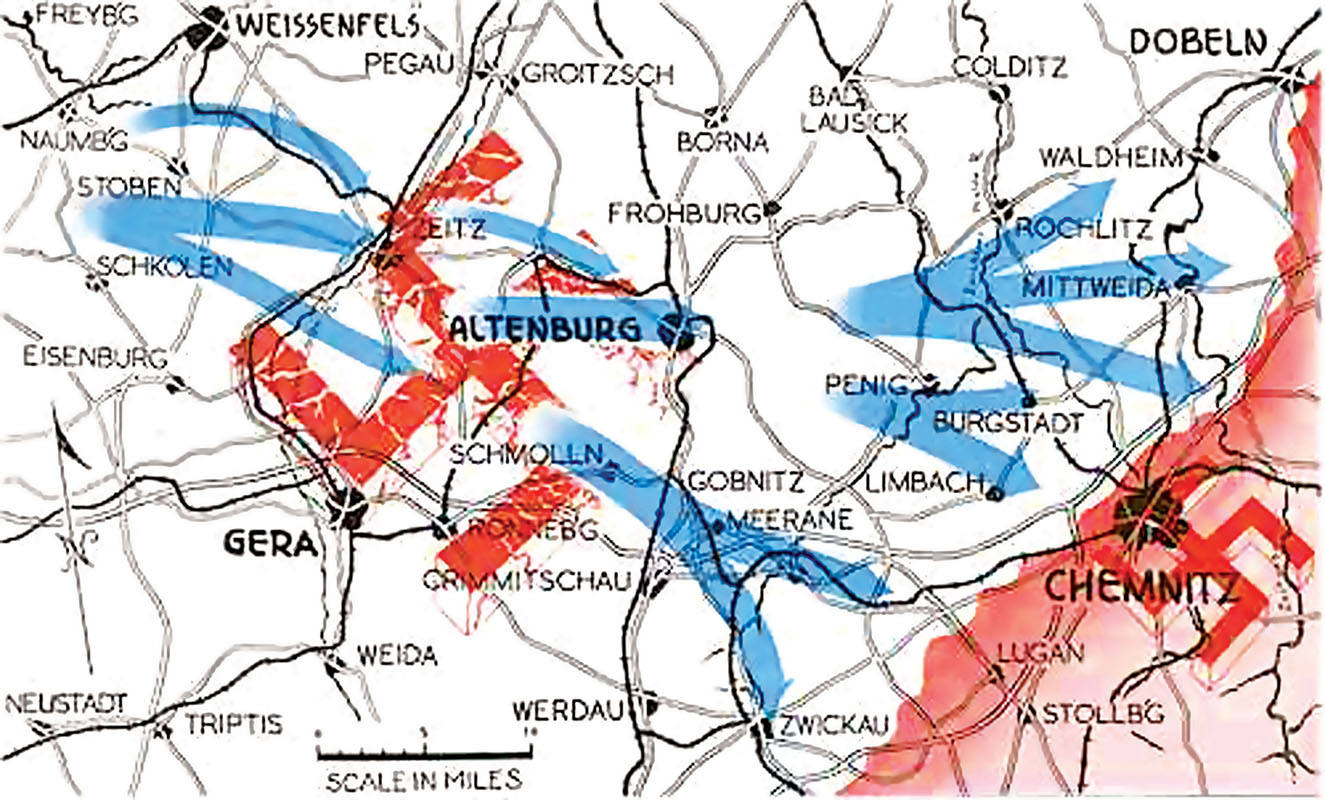

The 76th Infantry Division’s “race” across central Germany began on 2 April as it assumed the lead of all XX Corps infantry divisions following in the wake of the 6th Armored Division. The tankers just motioned German soldiers, who tried to surrender, rearward.2 The hemorrhaging Wehrmacht was disintegrating rapidly. The deeper the Allies pushed into the Western Front, the faster the pace became. There were two almost parallel lines on the map along a latitude that straddled the Autobahn. Between them the 385th Infantry advanced like a lawnmower cutting a swath across an enormous lawn. “Only this lawn had towns on it, Germans, casualties and death, and hundreds of PWs, liberated slaves and Allied Prisoners of War. Jeeps and trucks careened wildly from town to town, hauling up in the center of villages where the ‘Doughs’ scrambled from trucks behind the tanks to clear whatever was necessary.”4 The 76th Infantry Division, as part of Major General (MG) Walton H. Walker’s XX Corps in Lieutenant General (LTG) George S. Patton’s Third Army, was pushing in a wide swath towards Chemnitz, Czechoslovakia, on the Elbe River.5 This massive eastward offensive was the reason CPT Terry Vangen was conducting a reconnaissance in front of his troops on 6 April 1945.

The reconnaisance party was halted by enemy tank fire four hundred meters short of Ungerstrode. CPT Terry Vangen, in the lead jeep, stood up to get a better view. When enemy machinegun fire shattered his windshield, both trailing jeeps quickly reversed to escape the ambush. Caught in the “kill zone” of the ambush, CPT Vangen, his jeep driver, and artillery sergeant [Sergeant (SGT) Montour] leaped from their jeep and scrambled for cover in a streambed adjacent to the road. As the three Americans started backtracking down the stream, a German soldier shouted, “Halt!” Vangen, covering the rear, crawled up the embankment. He shot an approaching German with his M-1 carbine. This action prompted another enemy soldier to toss a “potato masher” handgrenade down into the streambed. Shrapnel from the exploding grenade wounded the driver in the leg and the concussive effect knocked SGT Montour unconscious.

When the American captain raised up again, a volley of small arms fire from behind him shattered his carbine, split his thumb apart, cut his face, and slashed an ear. As Vangen dropped the useless weapon, he looked up to see enemy soldiers all around pointing rifles at him and his driver. He quickly raised his hands before the Germans could shoot him again, realizing that further resistance was futile. Several German soldiers then jumped down into the streambed. When Vangen turned to help the unconscious SGT Montour, they prodded him away and onto the road with their rifle barrels. Now, the company commander had to deal with war as a PW.6

How Captain Terry Vangen dealt with his capture demonstrated that practicing SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape) elements would be based on many variables in combat. SERE training is mandatory for Special Forces, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) pilots and flight crewmen, and other selected Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF). Knowing his background and experience one can appreciate how CPT Vangen capitalized on them to escape and rejoin his unit. This account shows today’s ARSOF soldiers how important mental and physical strength in war are.

Fortunately, Captain Terry Vangen was not typical of company commanders in the National Guard infantry divisions mobilized for war. He had enlisted in a reduced strength Regular Army (RA) in 1935 to become a professional soldier because jobs were very scarce in north-central Minnesota (the Mesabi iron range region) during the Depression. Vangen joined the Army to help his family.7 The Army clothed, housed, fed, and paid its soldiers. Though meager by today’s standards, $21 a month helped support his family in Pengilly, MN. His father was a Norwegian immigrant who worked as a seasonal lumberman and mine driller. One key aspect in the poorly-funded and understrength RA infantry and artillery regiments service-wide was sports.

The big, (6’3”), natural athlete excelled as a baseball and basketball player for the 3rd Infantry Regiment at Fort Snelling (near St. Paul), MN, two hundred miles from home. The 3rd Infantry did annual marksmanship qualifications, road marches, and small-scale maneuvers at Camps McCoy in Wisconsin, and Ripley in Minnesota in the summer. Natural leadership and the ability to get things done earned promotions and more responsibility—corporal in two years, sergeant in three, and then squad leader. “These were rapid promotions at the time. I began to hustle when I found out that my two younger brothers were being paid thirty dollars a month in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC),” chuckled Vangen.8

However, Vangen discovered that sergeant’s pay was insufficient when he was sent to a high school ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Corps) assignment in Davenport, Iowa, in the fall of 1940. Detached enlisted men (DEML) received a small stipend from the school, but it did not offset free room and meals in the barracks. The sergeant, like his supervisor, a WWI veteran and first sergeant, worked part-time at a gas station to make ends meet. It was his promotion to staff sergeant shortly before Pearl Harbor that enabled Vangen to get married. Congress’ declaration of war changed SSG Vangen’s life plans radically as it did for millions of Americans.9

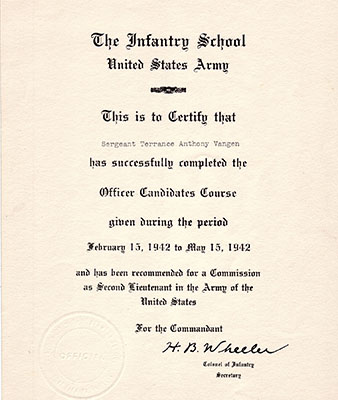

A Regular Army officer and WWI veteran in charge of ROTC, Major Clark, recognized the potential in this promising professional soldier. “He wanted me to apply for Officers Candidate School (OCS). MAJ Clark said that an Army mobilizing for war needed experienced, quality NCOs to become officer leaders. It was a daunting prospect for me, a GED high school graduate, but MAJ Clark and my wife had confidence that I could make it,” recalled Vangen.10

In early February 1942, SSG Vangen entered Infantry OCS at Fort Benning, Georgia. The academics proved tough for the older soldiers. Physical training, tactics, weaponry, and the field exercises were a “snap” for them. Better-educated candidates (some were college graduates) tutored in exchange for leadership help. “I had to spend a lot of time studying in the latrine after ‘lights out’ at night, but it paid off. Academics washed out more than fifty percent of my OCS class. Eighty of us graduated,” said Vangen.11

In May 1942, the new Army Reserve second lieutenant (2LT) reported in to the 76th Infantry Division (ID) at Fort Meade, Maryland. The 76th ID was a National Guard division from New England that had just been activated. The NCO cadre were Regular Army soldiers from the 1st Infantry Division. Lieutenant Vangen was to be 1st Rifle Platoon Leader of F Company, 2nd Battalion, 385th Infantry Regiment. “Our original regimental commander was Colonel (COL) Clifford J. Mathews, a West Point WWI veteran, but still tough. Murphy did every twenty-five mile road march. He was the epitome of a real soldier who led us through all training. COL Mathews stressed the importance of Ranger tactics and EIB (Expert Infantry Badge) qualification for NCOs and soldiers at Camp A.P. Hill in Virginia. We were good enough to be division aggressors during XVI Corps winter maneuvers held in the Ottawa National Forest along Lake Superior in northern Michigan (near Watersmeet) in early 1944. Though COL Mathews was an outstanding leader, he was deemed too old for combat. It was a shame because he made us into officers,” remembered Vangen.12

Though the 76th was hit heavily for officers and sergeants before the North African and Normandy invasions and twice more to fill divisions going overseas earlier, LT Vangen was considered too good to lose. After about a year as the F Company 1st Platoon leader, he became the Weapons Platoon leader, then served as the company Executive Officer, and was the acting Company Commander until he took command of E Company when he was promoted to captain. This happened shortly before Thanksgiving 1944 when the 385th Infantry left Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts, bound for England. When CPT Vangen entered combat, he had been commanding units in 2nd Battalion for thirty months. This was unusual but not unheard of for OCS officers with prior enlisted time. The Army needed experienced soldiers in combat, but Reserve Officers had limited careers.13

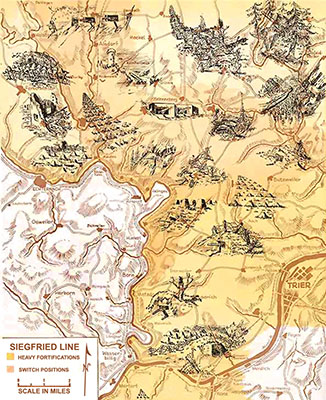

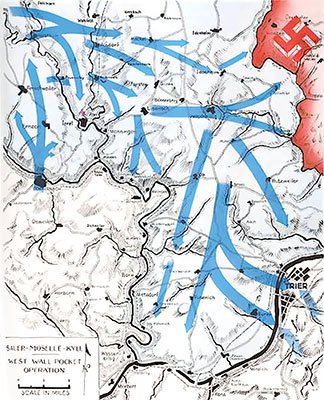

The 76th ID boarded U.S. Navy LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) in regimental increments in mid-December 1944 for LeHavre, France. The 304th, 385th, and the 417th Infantry Regiments were then loaded into French railcars for movement north. Truck convoys carried them to the MLR (Main Line of Resistance) near Ortho, Luxembourg just before Christmas. The 385th, Vangen’s unit, replaced a cavalry regiment screening south of the Sauer River. The 76th, like many other untested divisions, was being integrated into the line during the holiday lull to get some exposure to combat. Initially, combat patrols (six to ten soldiers) were led by company commanders. It was a period of “night patrols and nagging little skirmishes … barns burning in the night, and first casualties” because the division had been in reserve during the Battle of the Bulge.15 But, in January 1945, the 76th crossed the Sauer River to spearhead the XII Army Group push to Eternach on the Saar River. After following their sister regiment, the 417th Infantry, into Germany, the 385th led the division assault on the thickest portion of the Siegfried Line near Minden (forty pillboxes per square mile of rolling terrain with little vegetation, trenches and minefields, and devoid of roads).16

On 19 February 1945, CPT Terry Vangen, Company E, 385th Infantry, was awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action. Intelligence reports indicated that the nearest two pillboxes that his company was to capture contained friendly troops. Rather than putting them at risk, Vangen with one volunteer ran forward under enemy sniper and mortar fire to investigate. “It was the rifleman against concrete and steel.”17 After finding an American officer and three enlisted soldiers who had been cut off from their unit, Vangen and his assistant took turns providing covering fire that enabled the four battle-weakened and wounded U.S. soldiers to reach friendly lines. That completed, CPT Vangen, under “extreme artillery and sniper fire,” personally led attacks on three other enemy-held pillboxes. Though wounded he continued to press the attack forward enabling his company to breach the first lines of pillboxes constituting the Siegfried Line.18 This act of heroism, however, brought Vangen some unforgettable attention from LTG George Patton, the legendary Third Army commander.

“I just happened to be in the rear when Patton was visiting 385th Infantry headquarters. I stopped loading ammo into my jeep trailer just long enough to render a snappy salute to General Patton as he passed by. He asked Colonel Onto P. Bragon, my regimental commander, who that was handling the ammo nearby. When COL Bragon proudly responded, ‘Captain Terry Vangen. He was just awarded the Silver Star,’ LTG Patton replied, ‘Get some insignia on him. He doesn’t look like a captain,’ and got into his jeep and left,” said Vangen. “After that, I kept my captain’s bars visible … until I was captured in April.19

The introduction to this article ended with two wounded American soldiers, CPT Terry Vangen and his jeep driver, being hustled north from Ungerstrode by the Germans on 6 April 1945. The wounded artilleryman, SGT Montour had been left behind, unconscious in the streambed. (*Note: When E Company, 385th Infantry captured Ungerstrode a few days later, Montour was found in a barn. Someone had taken him there for safety, but had not treated his wounds.) 20

“I ditched my helmet with the painted captain’s bars while climbing up the stream bank and somehow got my rank off my shirt collar. As we closed on the town American artillery opened up and we were hurried to a defiladed side of a hill just beyond the impacting rounds. A well-camouflaged civilian car was parked nearby. The two of us were quickly loaded inside and taken to a nearby hospital. I initially resisted a doctor wielding a hypodermic needle thinking it was a drug. When he said, ‘Tetanus,’ I relaxed, took the shot, and permitted him to clean, treat, and bandage my wounds. The last time I saw my driver was when I was led away for interrogation,” said Vangen.21

Interestingly, “every German officer who could speak English interrogated me. I must have been questioned twenty times as they shuttled me from place to place. They continually asked me if we were fighting the Germans or the Nazi Party. I said that I was fighting on orders and was not in a position to discuss politics. One officer wearing jodhpurs showed me an issue of their weekly propaganda newspaper [most likely Das Reich] that had an article entitled, ‘Jerry PWs to Be Turned Over to Russia as Slave Laborers After War.’ He wanted to know whether it was true that American soldiers killed all the SS troops they captured. My basic reply was name, rank, and serial number, but they already knew my division and regiment,” Vangen said.22

Constant attacks by American forces had forced the Germans to reorganize depleted elements to man hasty defensive positions where artillery fire and advancing tanks further reduced their ranks. “For three days I was marched from one town to another and sometimes right back the way we had come. Obviously, they didn’t know what end was up. One day we were retreating faster than usual and I was allowed to ride on an ammunition truck ahead of a fuel tanker. A couple of Army Air Corps P-38s strafed the convoy and set the fuel truck afire. The ammo truck on which I was riding managed to find cover and escape,” related Vangen.23

“Some nights, I was put in a building alone; other times I had company … with one to three other PWs. On the night of 8 April, I was locked up with a Dutch civilian detainee and two other American soldiers. That was the only time I had potato soup with some black bread. Normally, it was only two slices of bread a day. That night the daughter of a cook managed to “‘palm’ me a K-ration cigarette as I waited in line to be fed. I was quite surprised when a guard asked if I wanted a light … in English! I was so grateful that after a few quick drags I passed it over to him,” said Vangen.

“When we were rousted out at 3:00 A.M. the next day, I thought that we were to be shot after a decent meal and a cigarette. Thankfully, that wasn’t the case. American forces were very close,” related Vangen. “It was obvious that the Germans were becoming desperate. I sensed the time had come to find an opportunity to escape.”24

“The four of us were put between two groups of Germans as they moved down a farm road in column. There were about thirty enemy soldiers in each group. Just as daylight was breaking artillery began falling all around us. It was a typical heavy barrage that preceded another ground attack, but I decided to take advantage of the discomforting noise and nearby explosions. I began shouting, ‘Stop! Stop! We’re going to be killed,’ and ran around screaming and waving my arms at my captors, pretending to be shell-shocked. I managed to work to the rear of the second group of German guards when the road deteriorated at a stream crossing. Everyone was slipping on the slick moss-covered rocks, losing balance, stumbling and falling, and getting wet. The Germans were in a hurry to escape the ‘walking’ artillery preparation knowing that the infantry would be attacking close behind,” related Vangen.25

“I purposefully tripped and fell down among the rocks with a loud crash. Then, I grabbed my right knee and starting moaning and ‘writhing in pain.’ The Germans generally ignored me in their haste, I guess figuring that I would eventually get up and hobble after them. As they moved out of sight, they sent a young soldier back. By then the main body was well out of sight. Though he approached me cautiously, the young man was carrying a cylinder-fed sub-machinegun slung over his shoulder. I made a few fainthearted couple of attempts to get up, theatrically splashing the water as I fell back down. But, they were sufficiently convincing to get him to offer a hand,” Vangen said.26

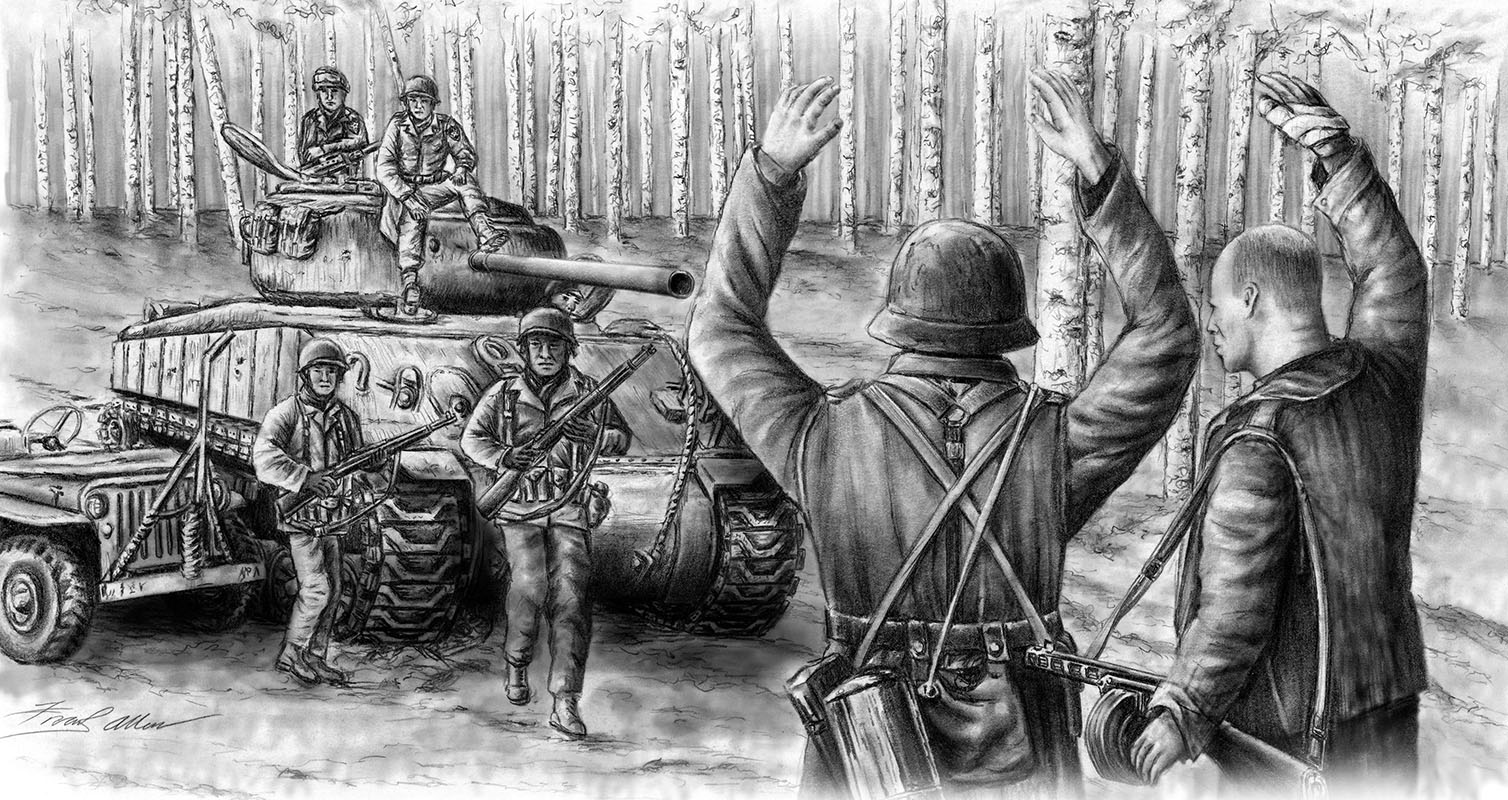

“As he bent over to reach under my arm, I sprang up, stripping him of his weapon. He offered no resistance, except to say, ‘No kaput! No kaput!’ (Don’t kill me!) while raising his arms high. With our roles reversed, I motioned for him to get in front of me and used the gun barrel to point towards some thick vegetation a few hundred meters away. We needed to get under cover quick. The U.S. artillery was coming closer. In that wooded area we found large stacks of firewood. I immediately got down to burrow between the stacks and to camouflage myself with branches. My young prisoner saw the wisdom of getting down among the stacked firewood but declined to cover himself up. He simply sat down, content to be ‘out of the war.’ Together, we spent that morning, afternoon, and night in that wood pile awaiting our fates.”

“At daybreak the next day (17 April 1945), I was jerked awake by the sound of a tank nearby. My prisoner, still sitting there, had heard it also. I was pretty sure by the sound of the engine noise that it was a Sherman and stripped off my covering of branches. I crawled to the end of the woodpile to investigate. There was definitely a tank about seventy-five meters away with its engine idling, but the silhouette was obscured by the vegetation. I had to move closer to be sure, but I didn’t want to be shot … especially by my own guys,” said the American infantry company commander cum PW.27

“I led the way as we inched slowly towards the idling tank. Fortunately, our movement was covered by the engine noise. Then, I spotted a jeep with Americans next to the tank. When we got about fifteen meters away, I began shouting loudly, ‘Hey! Hey! Hey! I’m an escaped American PW and I have a German prisoner with me.’ Having gotten their attention, I yelled, ‘We’re going to stand up with our hands raised and for heavens sakes, don’t shoot us! I’m Captain Terry Vangen, E Company, 385th Infantry.’ As we stood up, I’ll never forget seeing ‘Indianhead’ patches on their uniforms. They were definitely 2nd Infantry [Division] guys.”28

“They took charge of my grateful German prisoner, gave me a cigarette and some coffee, and we were taken back to their regimental headquarters. The CP alerted the 385th, who took me off MIA (Missing in Action), Presumed Captured status, sent the appropriate notifications to my wife and family, and I finally rejoined my battalion the next day. It seemed that SGT Montour, my wounded artilleryman, had explained what occurred on 6 April 1945 and thought that I had been captured. That ended my eleven days as a PW.”29

The 385th had been leading the division charge behind the 6th Armored until 17 April when its turn in reserve caused it to be attached to VIII Corps. It relieved 4th Armored Division units on the eastern side of the Zwickauer Mulde River, just short of the Elbe River, ten miles from Chemnitz, Czechoslovakia. The 76th ID was waiting to linkup with the Russians when CPT Terry Vangen rejoined his regiment. The 385th Infantry was collecting displaced persons, citizens of Chemnitz, and surrendering German soldiers fleeing the Russians and relocating them to refugee camps and PW camps behind American lines.30

“As to what kept me going and determined to escape if given the chance, I was married with one daughter (Sharon), a competitive athlete and an old soldier (ten years service in 1945) with good survival instincts, and irritated with myself as a leader for getting into something that led to my capture,” said Vangen reflectively.31 Thus, it was that he survived captivity, resisted numerous interrogations, managed to escape, evade, and avoid recapture. When Vangen escaped he was more than a hundred miles from where he was originally captured and thirty miles from his unit which was on the right flank of the 2nd Infantry Division that was part of V Corps. It took more than two days for him to rejoin his regiment because the 76th Infantry had relieved 4th Armored Division in the VIII Corps area. “I vividly remembered that our first KIA overseas was the result of friendly fire. That’s why I was being so cautious when I approached those American troops in the woods that final day,” added Vangen.32

EPILOGUE

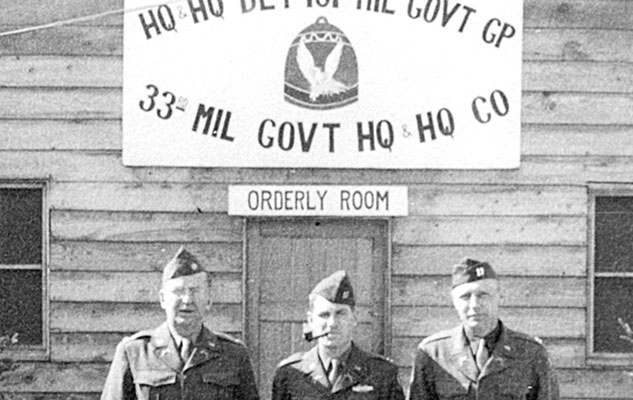

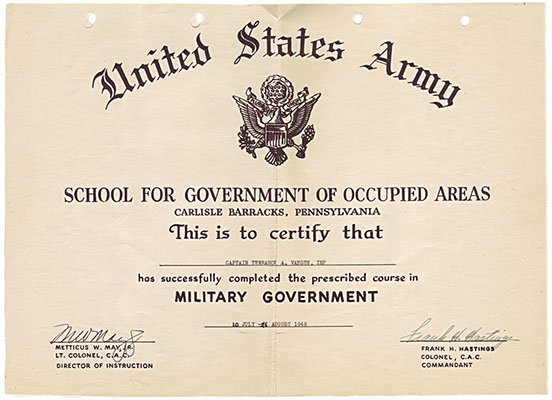

The war in Europe ended less than a month later and just six months after the 76th Infantry Division crossed the English Channel to France. As a former prisoner, CPT Terry Vangen was given priority to return home, but not released from active duty. Because he was a U.S. Army Reserve indefinite officer, he was sent to the Army’s Military Government School at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, in the fall of 1945, for two months. The military government and occupation model being taught at Carlisle Barracks was the European one just as it had been after WWI and during and after WWII in Europe. CPT Vangen found that the school training had little relevance when he was assigned to the 101st Military Government Group in Korea in 1946. Vangen and his family spent almost three years in occupied South Korea.33

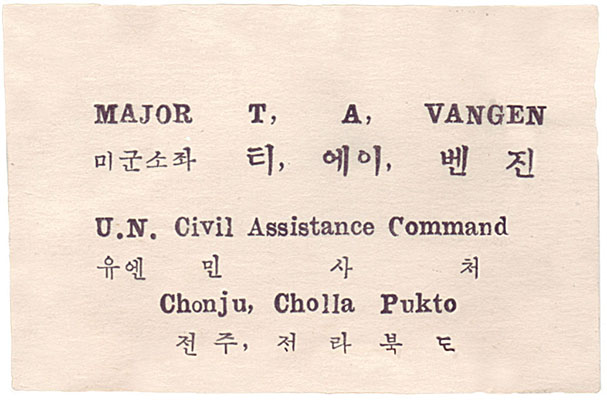

For this reason he was sought by the United Nations Civil Assistance Command, Korea (UNCACK) when the war broke out. COL Charles Munske selected him to accompany his team to P’yongyang, North Korea, in late October 1950, to form a short-lived UN military government in the Communist capital city. Vangen was slated to be the Public Welfare Officer. Their convoy of military government personnel was among the last to leave P’yongyang the day before Communist Chinese Forces recaptured the North Korean city (5 December 1950).34 CPT Vangen celebrated the New Year in Taegu before being reassigned to Chonju in Challo Puk-to province where his Economics Officer was 1LT John Montgomery Belk (later the CEO of three hundred department stores in the southeast, southwest, and mid-Atlantic United States).35 LTC Terrance A. Vangen retired from the Army in 1958, after three years as the U.S. Army post commander for Worms/Rhine, Germany. After twenty-five years with the Civil Defense Preparedness Agency (DPA) he retired again. Today, he spends the warm months in his hometown, Pengilly, MN, and the winters in Orange Beach, Alabama.

ENDNOTES

- Charles B. MacDonald, The Last Offensive. United States Army in World War II: The European Theater of Operations (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army, 1973), 205. [return]

- MacDonald, The Last Offensive, 379. [return]

- 1LT Joseph J. Hutnick and Technician Four Leonard Kobrick, eds., We Ripened Fast: The Unofficial History of the 76th Infantry Division at http://www.76thdivision.com/385th/History_385th_005.html, http://76thdivision.com/385th/History_385th_006.html. [return]

- MacDonald, The Last Offensive, 379. [return]

- Retired LTC Terrance A. Vangen, interview by Dr. Charles H. Briscoe, 15 August 2007, Pengilly, MN, digital recording, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Vangen interview and date, and untitled and undated 1945 newspaper article by Army War Correspondent, personal papers of Terrance A. Vangen, Pengilly, MN, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter cited as War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007. [return]

- Hutnick and Kobrick, We Ripened Fast at http://76thdivision.com/385th/History_385th_005.html. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and Hutnick and Kobrick, We Ripened Fast at http://76thdivision.com/385th/History_385th_005.html. [return]

- Hutnick and Kobrick, We Ripened Fast at http://76thdivision.com/385th/History_385th_005.html. [return]

- 76th Infantry Division, General Order 46 dated 12 March 1945, awarded the Silver Star Medal to Captain Terrance A. Vangen, F Company, 385th Infantry Regiment, for gallantry in action near Minden, Germany, on 19 February 1945, and undated Pengilly newspaper clipping, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and MacDonald, The Last Offensive, 115. LTG George S. Patton, Third Army commander, had strode into the division command post early on 26 February 1945, placed a fist on the ancient Roman city of Trier on the Moselle River, and ordered its envelopment by the XX Corps from the south and the 76th Infantry Division from the south. Hutnick and Kobrick, We Ripened Fast, 102. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent, article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Hutnick and Kubrick, We Ripened Fast at http://76thdivision.com/385th/History_385th_006.html and MacDonald, The Last Offensive, 384. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 15 August 2007 and War Correspondent article. [return]

- Vangen interview, 16 August 2007. [return]

- Retired Colonel Charles R. Munske, Chief, P’yongyang and P’yong-dan Province CA Team, Eighth U.S. Army, Korea (Forward), North Korea, undated handwritten notes, 19 October-5 December 1950, and Charles R. Munske, letter to his wife, 7 December 1950, courtesy of Judy Munske, Report on Activities of the P’yong-dan-Namdo Civil Assistance Team (n.d.), and retired LTC Loren E. Davis, telephone interview by Dr. Charles H. Briscoe, 2 February 2005, digital recording, and Vangen interview, 16 August 2007, copies in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- Vangen interview, 16 August 2007 and “Former Charlotte mayor, longtime Belk CEO dies,” Fayetteville Observer, 8 September 2007. [return]