SECTIONS

DOWNLOAD

Inserted at 7:00 p.m. by Navy PT boat onto the deserted beach, the small team moved stealthily along the trail until it reached its objective at 2:00 a.m. Two local guides were sent into the tiny village to obtain the latest information on the enemy disposition and ascertain the status of the personnel held hostage there. On the guide’s return, the team leader modified his original plan based on their information and the men dispersed to take up their positions.

The leader with six team members, the interpreter, and three local guides moved to the vicinity of a large building where eighteen enemy soldiers slept inside. Two team members and one native guide took up a position near a small building occupied by two enemy intelligence officers and a captured local official. The assistant team leader, four men, and two guides were to neutralize an enemy outpost located more than two miles away on the main road to the village. The outpost was manned by four soldiers with two machine guns. This team would attack when they heard the main element initiate their assault in the village.

The team leader opened fire on the main building at 4:10 a.m. and within three minutes his team killed or wounded all the enemy combatants. The two enemy officers in the small hut were killed and their hostage released. In the village, the interpreter and the native guides went from hut to hut gathering the sixty-six civilian hostages. As soon as everyone was accounted for, the group began moving to the pickup point on the beach. The assistant team leader and his men were unable to hear the brief gun battle in the village and waited until 5:30 before attacking the guard post from two sides, killing the four enemy soldiers. After neutralizing the guard post, the team moved to the pick-up point, secured the area, and made radio contact to bring in the boats for the evacuation. The main body with the newly-freed hostages soon arrived. By 7:00 a.m., everyone was safely inside friendly lines.1

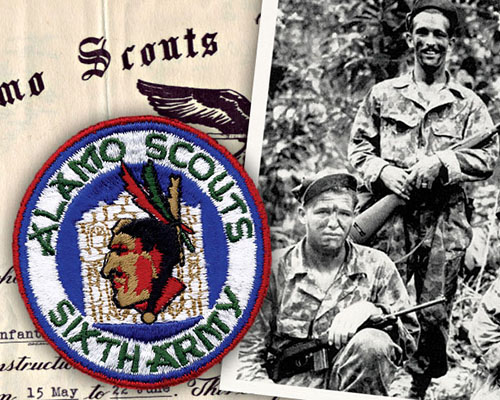

This well-planned, flawlessly executed hostage rescue could easily have come from today’s war on terrorism. In reality, it took place on 4 October 1944 at Cape Oransbari, New Guinea. The team that rescued sixty-six Dutch and Javanese hostages from the Japanese were part of the Sixth U.S. Army’s Special Reconnaissance Unit, called the Alamo Scouts. This article will look at the formation, training, and missions of that unique special operations unit.

The Japanese Advance

Following the 7 December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese military was on the march. The Imperial Army had been fighting in Manchuria since 1931 and was a veteran, battle-tested force. The Japanese grand strategy was to drive the European nations from their colonial holdings in Asia and implement the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, an involuntary assembly of Asian nations under Japanese domination. In December 1941, Nazi Germany occupied the Netherlands and France, and the British Commonwealth was locked in a struggle with the Axis. The United States was preoccupied with building up its own military forces and providing war materials to the embattled British. Japan chose this time to launch their attack on Pearl Harbor, and begin offensive operations throughout East Asia. The initial months of the war were a string of unbroken Japanese victories.

August 1942 was the high-water mark for the Japanese military. The Imperial Army captured Malaya and Singapore, occupied Borneo, Sumatra, and Java in the Dutch East Indies, and marched into Thailand. They pushed the British out of Burma, and dealt the United States a major defeat in the Philippines. Japanese forces swept south and east into New Guinea, where they established major bases at Rabaul on New Britain Island, and Tulagi in the Solomon Group and occupied the Marshall and Gilbert Islands in eastern Micronesia. They pushed north to seize Attu and Kiska in the Aleutians. Their forces were threatening Australia when the U.S. Navy decisively defeated the Japanese Navy at the Battle of Midway in June 1942. On 7 August 1942, the United States and her allies attacked Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Tanambogo, effectively checking further Japanese expansion.2 From this point on, the Japanese were forced to adopt a defensive posture to consolidate their holdings and prepare to fight off the growing strength of the Allies.

Maritime operations against the Japanese took place in two theaters. The Southeast Asia Command was under British control and led by Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. The Pacific Theater was divided into two areas. The largest was the vast Pacific Ocean Areas (POA) commanded by Admiral (ADM) Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, The POA extended from the continental United States westward across the ocean to Japan and included most of the Pacific islands. The South Pacific area was commanded by Rear Admiral Robert L. Ghormley. The second subdivision, the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), encompassed Australia, New Guinea, the Dutch East Indies, and the Philippines and was under the command of General (GEN) Douglas A. MacArthur.3 It was in the SWPA that the Alamo Scouts were created and operated.

The SWPA and Sixth Army

After his evacuation from the Philippines to Australia in March 1942, GEN MacArthur, was installed as the Commander in Chief of the SWPA, a joint command composed of United States, Australian, and Dutch forces. Of the major theaters of World War II, only the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI) was more poorly resourced than the SWPA. MacArthur’s General Headquarters (GHQ) directed three subordinate sections, the Allied Air Forces (Lieutenant General George C. Kenney, U.S. Army Air Forces), Allied Land Forces (General Sir Thomas A. Blamey, Australian Army) and the Allied Naval Forces, (Rear Admiral Arthur S. Carpender, U.S. Navy).4 In January 1943, MacArthur specifically requested that his long-standing friend Lieutenant General (LTG) Walter Krueger be assigned to command the newly constituted Sixth Army.5 In a move designed to keep the bulk of the American ground troops separate from the Allied Land Forces, MacArthur established a new command, the New Britain Force, around the Sixth U.S. Army, reporting directly to SWPA GHQ.6 The name was soon changed to the Alamo Force, because Sixth Army originally stood up in San Antonio, Texas, the home of the Alamo. LTG Krueger noted:

“The reason for creating Alamo Force and having it, rather than Sixth Army, conducting operations was not divulged to me. But it was plain that this arrangement would obviate placing Sixth Army under the operational control of the CG, Allied Land Forces, although that Army formed a part of these forces. Since the CG, Allied Land Forces, likewise could not exercise administrative control of Sixth Army, it never came under his command at all.”7