SIDEBARS

Training Teams Special Forces Mission Vietnam 1960

DOWNLOAD

In 1954, in accordance with the Geneva Accords, a separate military agreement between France and the Ho Chi Minh-led Viet Minh ended the fighting between the Communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the French Expeditionary Corps. Vietnam was partitioned at the 17th parallel. The Viet Minh withdrew north of the parallel and French forces to the south. New military equipment fielding and French troop strength was capped. Only replacements could enter South Vietnam and the general elections would be supervised by a United Nations International Control Commission (ICC). India, Poland, and Canada formed the ICC.1 From 1955 to 1960, internal political and military instability in the south did not go unnoticed by North Vietnam. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) in the 1950s mirrored the post Korean-War American Army organization and was trained to conduct conventional operations against Communist invasion by North Vietnamese Regular Army forces. Little consideration was given to counterguerrilla warfare.

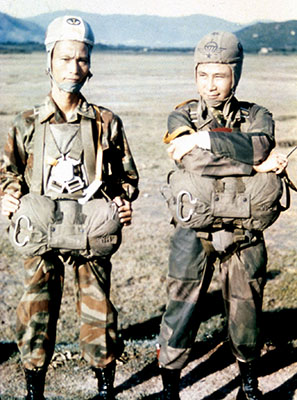

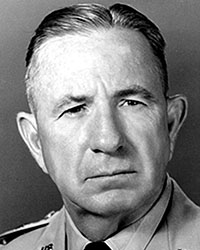

Capitalizing on the situation, North Vietnamese-sponsored Viet Cong (VC) guerrilla forces in South Vietnam escalated their insurgency in 1959, targeting military and political infrastructure. President Ngo Dinh Diem saw the need for dedicated counterinsurgency forces and asked Lieutenant General (LTG) Samuel T. “Hanging Sam” Williams, Chief, Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), Vietnam for help. The purpose of this article is to explain the 77th Special Forces Group’s MTT (Mobile Training Team) mission to train selected Vietnamese officers and noncommissioned officers as the ARVN Ranger cadre to develop a counterinsurgency capability for South Vietnam.

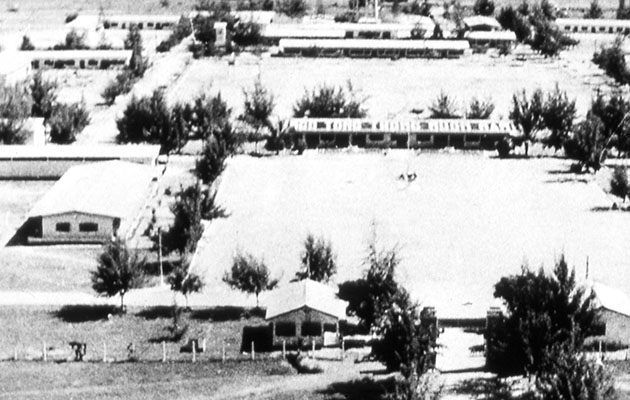

On 15 February 1960, before LTG Williams could respond, President Diem ordered ARVN division and military regional commanders to form Ranger companies from Army, Reserve, Retiree, and Civil Guard volunteers. Diem wanted each 131-man Ranger Company to have an 11-man headquarters section and three 40-man rifle platoons. By presidential directive, South Vietnamese commanders were ordered to have 50 of these Ranger Companies formed by early March 1960. Diem envisioned having a Ranger company in all thirty-two military regions and the remaining eighteen companies spread through the regular ARVN divisions.2 LTG Williams and General Isaac D. White, Commander of the U.S. Army Pacific disagreed; however, Elbridge Durbrow, U. S. Ambassador, supported Diem and sent a message to the Department of State outlining his position on 2 March 1960. The Department of Defense was asked to support. Anticipating future military requirements for Southeast Asia, the Army Chief of Staff, General Lyman L. Lemnitzer, directed the staff to develop courses of action to provide increased assistance to South Vietnam.