DOWNLOAD

The historians on the USASOC History staff often encounter intriguing SOF photos, documents, and memorabilia that require more research and cross-referencing before an article can be proposed. Many fascinating photographs that detail lesser-known aspects of ARSOF history are part of the closed collections. We wanted to share some of these “raw” historical materials. This is designed to prompt more veterans and family members to let the Veritas staff scan their photographs and records. This presentation of “raw” history explains a post-WWII intelligence unit, the Strategic Services Unit (SSU). These photographs illustrate a little-known intelligence mission after Japan surrendered. Thank you, John S. DiBlasi.

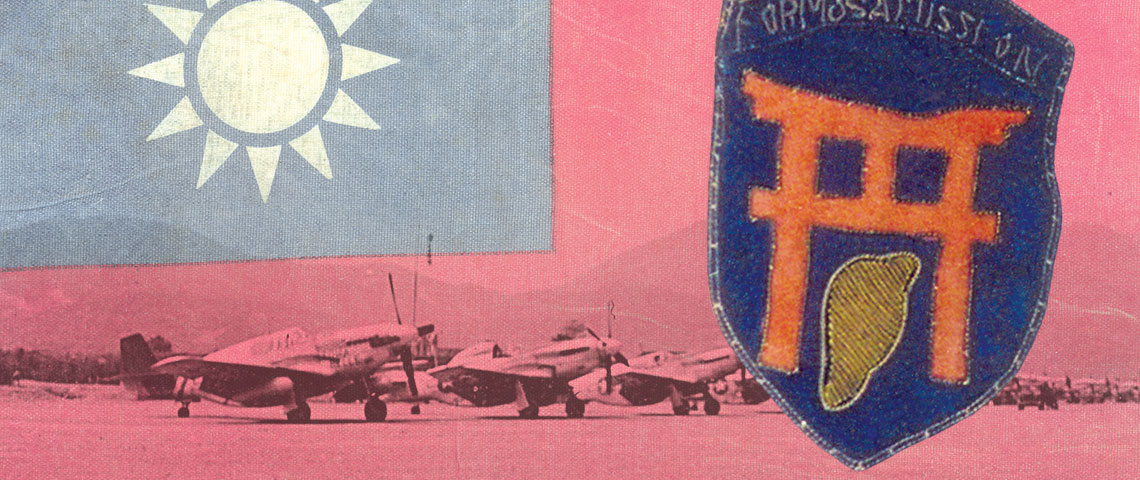

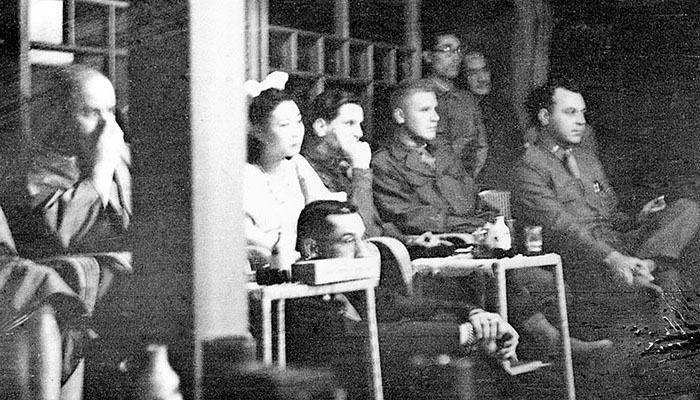

When President Harry S. Truman dissolved the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) on 1 October 1945, its operational personnel were transferred to the SSU, a newly created unit in the War Department. The SSU inherited the remaining OSS missions still in the field. One intelligence team was on the former Japanese colony of Formosa, now known as Taiwan. As part of the Japanese surrender, Formosa was transferred to Nationalist China. Japanese civilians and soldiers on Formosa had to be shipped back to Japan. The task of the Formosa Mission was to monitor the repatriation of the surrendered Japanese military.

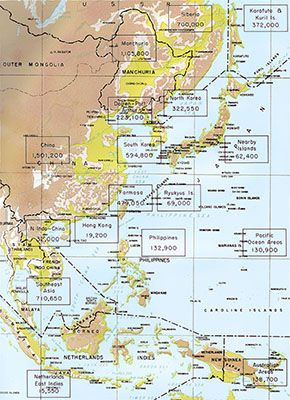

The repatriation of disarmed soldiers and civilians to Japan and the return of foreign “slave” laborers to their home countries was an enormous task not completed until 1949. On Formosa alone, 479,050 soldiers and civilians had to be transported back to Japan.1 The relocations were effected by the Shipping Control Authority for the Japanese Merchant Marine (SCAJAP), which used demilitarized Japanese warships and decommissioned U.S. Liberty cargo ships and LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) manned by Japanese seamen. By 12 April 1946, the repatriations from Formosa were essentially finished.2

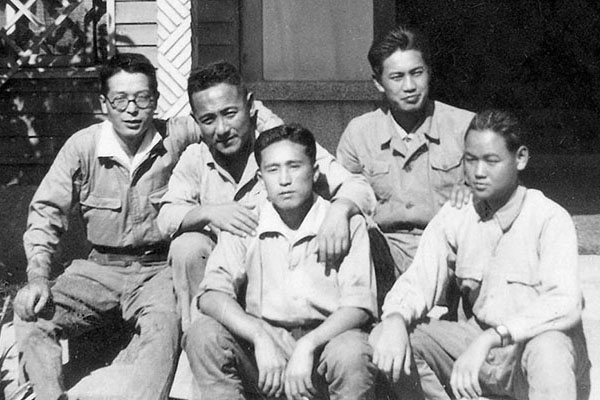

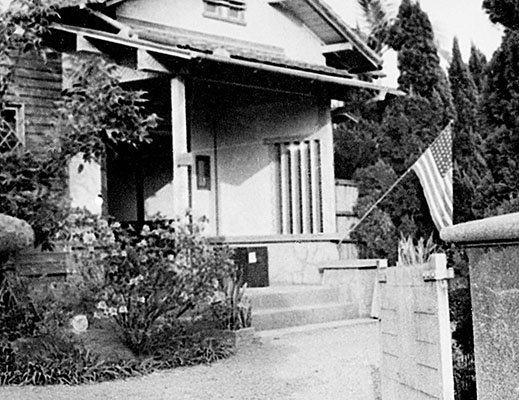

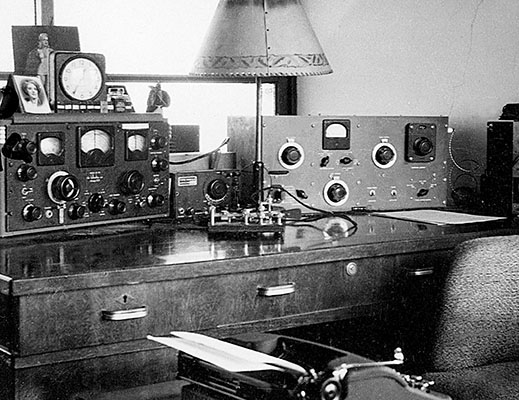

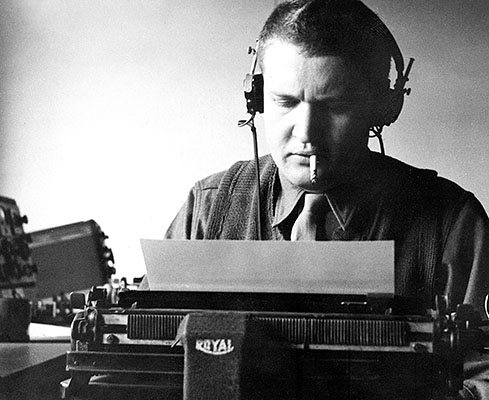

The Formosa Mission was a five-man SSU team led by a major. The commander coordinated with the Japanese and Chinese authorities to track the number of soldiers repatriated daily. Its radio station, call sign “RAM,” reported this information to SSU headquarters. Radioman Corporal John S. DiBlasi, detailed to the OSS/SSU from the U.S. Army Air Forces, sent those messages to Washington. The radio station was in the mission headquarters, an appropriated, functioning Geisha house.3 Cpl. DiBlasi was assigned to the Formosa Mission to accrue overseas points.

During the war, he had served as a radio operator with OSS/China on the SALEM Mission (Station PWF). SALEM was one of the teams supporting the joint OSS/14th Army Air Forces organization, the 5329th Air Ground Forces Resources Technical Staff (AGFRTS), popularly known as “Agfighters.” Their mission was to supply tactical air and ground intelligence to the 14th Air Force. Because the area of operations for the 14th Air Force was enormous, the OSS established networks of agents to supply target data. AGFRTS was so successful that its initial mission kept being expanded. From deep in enemy controlled territory, the organization provided weather reports and bomb damage assessments, monitored Japanese shipping, and operated an escape and evasion network for downed airmen.

In February 1945 the OSS assumed control of AGFRTS. The organization grew to include most OSS branches, including propaganda, counter-intelligence, and intelligence analysis.4 When the war ended, Cpl. DiBlasi had not earned enough “points” to come home yet. He volunteered for the Formosa Mission. This enabled a friend who did have enough points to return to the States.5 As the repatriation effort in Formosa was ending, the SSU morphed into another element.

By mid-1946, SSU had been folded into a new organization, the Central Intelligence Group (CIG), which became the CIA with the passage of the National Defense Act of 1947. Since Army SOF roots are intertwined with the OSS veterans that made up early Special Forces, it is appropriate to consider the SSU a legacy unit. The SSU performed an important interim mission in the turbulent post-war period that triggered the Cold War.