DOWNLOAD

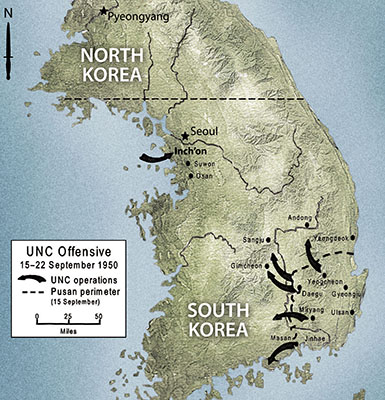

The initial efforts of the South Korean military and General Douglas A. MacArthur, Supreme Commander, Allied Forces Pacific (SCAP) and Commander-in-Chief, Far East Command (FECOM) to halt the June 1950 invasion from the north were unsuccessful. The Russian-equipped, trained, and advised North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) routed the poorly-led Republic of Korea (ROK) ground forces across a wide front. After Seoul fell to the enemy juggernaut, South Korean units conducted delaying actions southward. General MacArthur, plagued by limited naval assets and airlift, committed piecemeal under-strength (two regiment divisions with two battalion regiments), poorly trained U.S. occupation troops from Japan to bolster ROK forces. When Lieutenant General Walton H. Walker, the Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) commander, decided to form a defensive bastion around the southeastern port of Pusan, enemy pressure had to be reduced on the ROK and American forces to enable them to withdraw into that sanctuary.

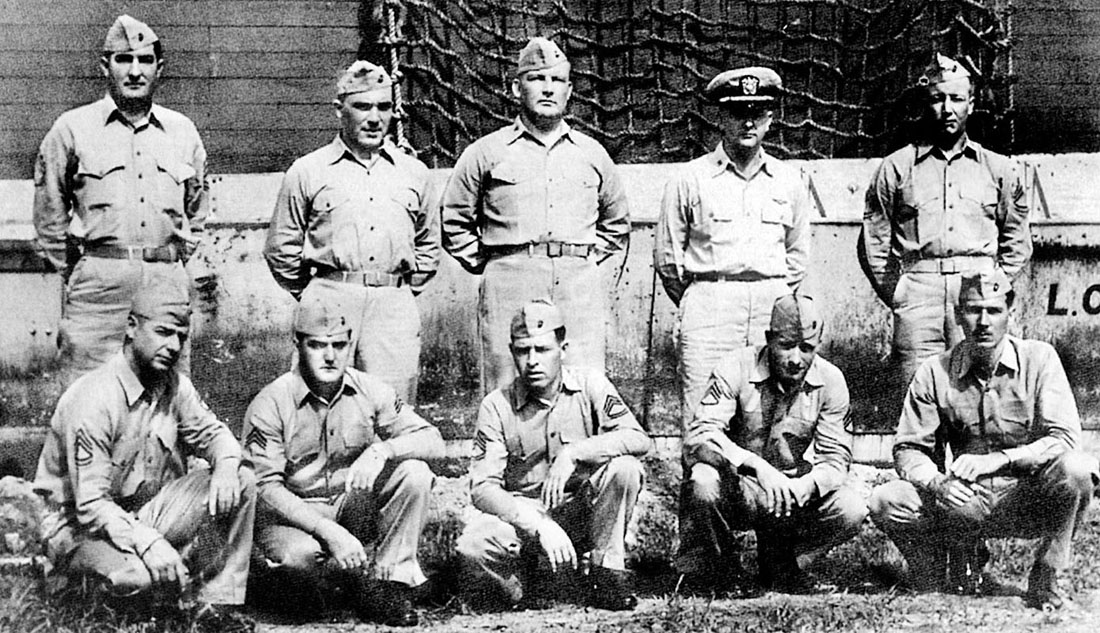

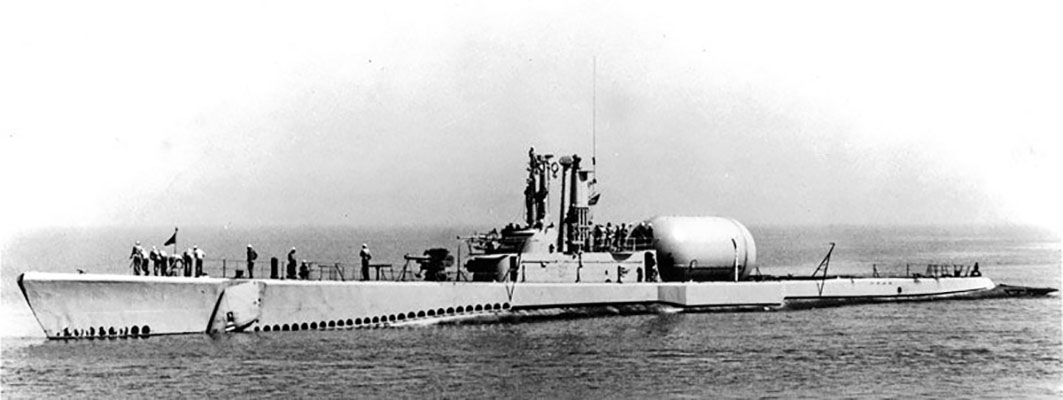

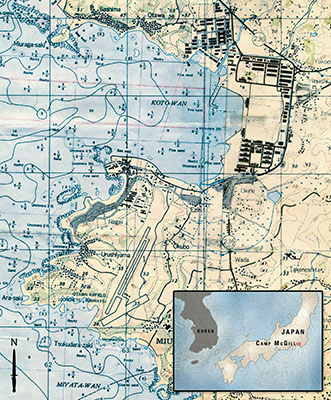

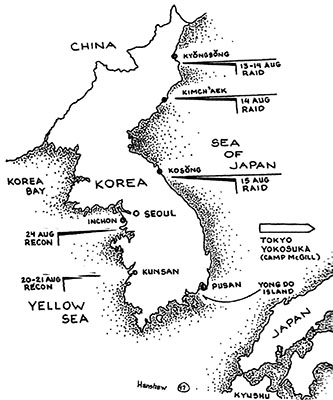

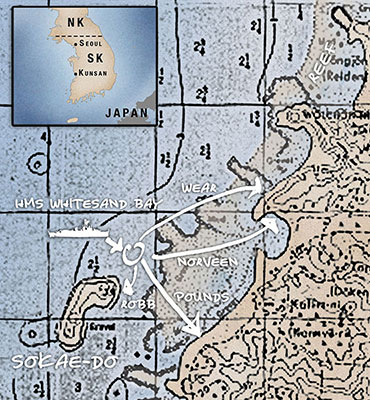

In late July 1950, after continual setbacks in South Korea, desperation drove General MacArthur to order the formation of commando/raider forces from FECOM headquarters, to solicit British Royal Navy Far East support, and to press U.S. Commander, Naval Forces Far East (COMNAVFE) “to conduct harassing and demolition raids against selected North Korean military objectives and execute deceptive operations in Korean coastal areas” to disrupt enemy lines of communications and supply and to deceive the enemy.1 “They were desperate times and every headquarters was ready to try anything,” said Lieutenant (junior grade) George Atcheson, after his Underwater Demolition Team 3 (UDT-3) element was pulled off a beach survey mission in Japan to successfully destroy a railroad bridge on the south coast of Korea on 6 August 1950.2 While this was happening, the FECOM Adjutant General (AG) screened records for candidates to organize a “Raider Company” from General Headquarters (GHQ) volunteers.

The Pentagon was no better prepared to deal with a conventional war in Asia than was General MacArthur’s Far East Command in 1950. The Russians had gotten the A-Bomb. Mao Zedong’s Red Army had pushed Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalist Chinese Army from the mainland to Taiwan (Formosa), but the defense of Europe against postwar Soviet expansion was the primary U.S. military mission. Most of the Army’s WWII special operations forces (six Ranger Battalions, the First Special Service Force, Merrill’s Marauders, MARS Task Force, Alamo Scouts, and the Mobile Radio Broadcasting companies) had been deactivated in the massive demobilization that followed V-J Day in 1945.