SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

The Ivanhoe Security Force (ISF) was a 2nd Infantry Division (2nd ID) counter-guerrilla unit that grew out of necessity shortly after the division arrived in Kyongsan, Korea, in September 1950. Since the 2nd ID was at full strength and fresh from the United States, its three infantry regiments were quickly moved into the defensive lines of the Pusan Perimeter. They replaced the 24th Infantry Division which was woefully understrength (down to 45% strength). But, their newly assigned defensive sector covered some 35 miles. The 2nd ID front stretched from the juncture of the Naktong and Nam Rivers in the south to the town of Hyonpung in the north.1 Facing them were the 105th Armored as well as the 4th and 8th Infantry Divisions of the North Korea Peoples Army (NKPA).2 The 2nd Infantry was spread thin over an area that was plagued by refugees heading south. Enemy infiltrations behind friendly lines disrupted command posts (CPs) as well as resupply routes.

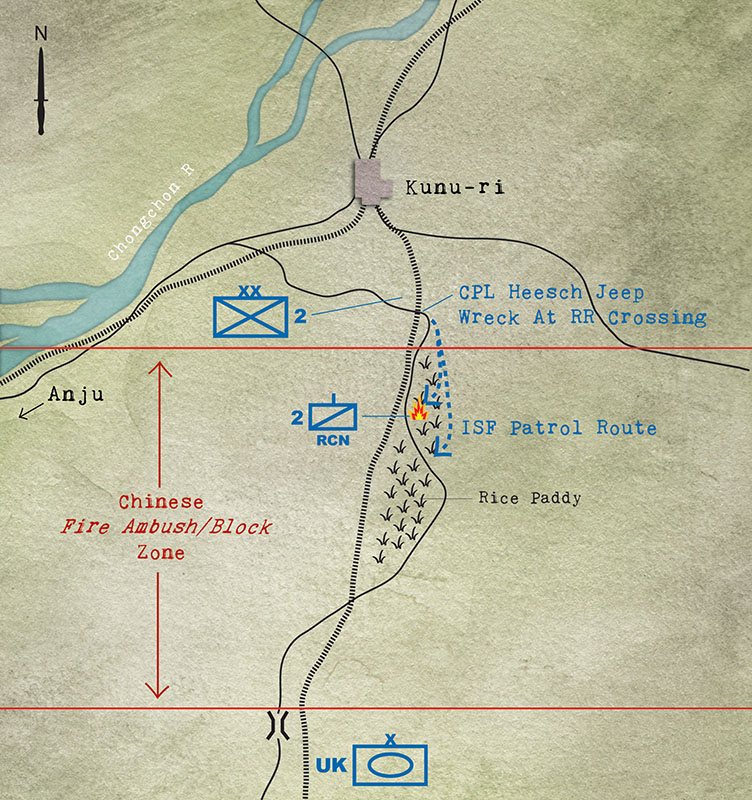

The threat prompted the creation of an American-led counter guerrilla force made up of South Koreans much like U.S. Special Forces (SF) trained and led indigenous Mike Forces in South Vietnam. The purpose of this article is to explain why the 2nd Infantry Division created this ad hoc, “off the books” indigenous counter-guerrilla force, who the American “advisors” were, and what role they had in organizing, manning, equipping, and fighting this element. They were doing what Army special operations forces (ARSOF) soldiers do today in Afghanistan and Iraq. Since the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-2 (Intelligence) directed ISF missions, their actions became closely intertwined with the major actions of the 2nd ID from August until late November 1950 during the disastrous withdrawal at Kunu-ri, North Korea. The Ivanhoe Security Force was sent wherever there was trouble in the 2nd Infantry area.3

The first elements of the 2nd Infantry arrived from Fort Lewis, Washington, on 31 July 1950.4 Corporal (CPL) Joseph C. Howard, 2nd MP Company and ISF remembered: “Married personnel had little time to move their families. Those who had cars had to sell at half their value. Hundreds of replacements were rushed into the division to bring it up to strength. On the ship over we had to train them on their assigned weapons because replacements came from finance, quartermaster, etc. But, we had plenty of time; the ship took seventeen days.”5 The reality of war came quickly.

On 7 August 1950, A Battery, 15th Field Artillery was attacked in the early morning by enemy forces who had infiltrated behind the front lines and gotten into their firing position. It was a “wake up call” for the artillerymen. They drove off the attackers and killed fifteen North Korean soldiers.6 Bands of South Korean dissidents and bandits, who had long populated the Taebaek and southwestern mountains, joined four reduced divisions of the NKPA II Corps to conduct limited guerrilla operations above and below the 38th Parallel.7

Hordes of white-clothed, steadily plodding peasants moved south along mountain trails and roads to saturate the division area as the infantrymen sought to drive off enemy patrols sent to scout ahead of a major attack. Intermingled among the displaced persons were Communist agents intent on collecting information, harassing, sabotaging, and attacking American forces behind the lines. They were very effective in those early days.8

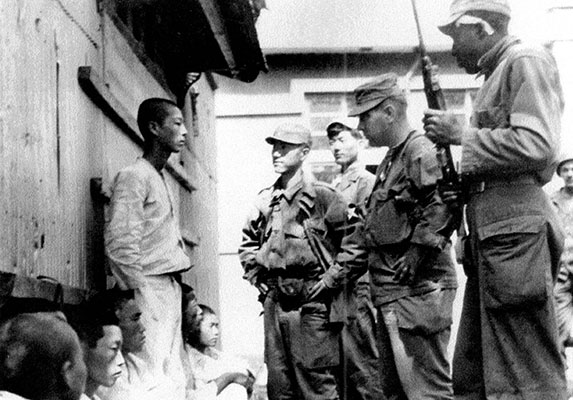

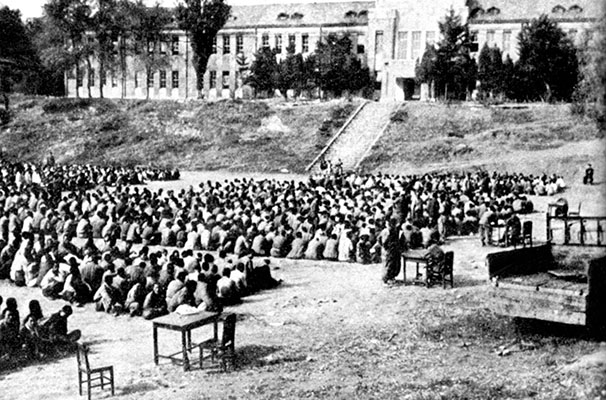

While the burden of controlling the refugees fell to every unit on the front line and in the rear, it was the primary responsibility of the 2nd ID Provost Marshal, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Henry C. Becker, the agents of the 2nd Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC) Detachment, and local South Korean police. Posted leaflet notices warned refugees that they would be shot for moving at night and advised them to stay clear of battle areas and unit positions. During daylight, MPs operated refugee screening posts on railroads, roads, and trails conducting cursory searches for weapons with mine detectors. Refugee assembly points were established at fifteen-mile intervals to allow rest and control movement. Food and water was provided before Korean police escorted groups through the division area to Susan-ni on the Naktong River.9 However, these control measures proved insufficient as night attacks behind division lines continued.

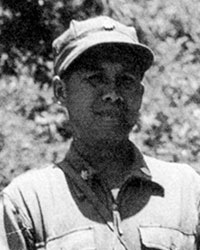

WWII veteran Major Jack T. Young, the 2nd ID Deputy G-2, volunteered to organize and train a special security force to deal with the refugee problems, collect intelligence, and counter guerrilla activities in the division rear areas.10 The Chinese-American born in Kona, Hawaii, was a 1936 graduate of Futan University, Shanghai, (bachelor’s degree in business administration). In 1938 he attended the Kuomintang Military Academy. Then, he led Nationalist Chinese units for General Chiang Kai-shek until 1943. After fighting guerrillas in Shantung Province, Nationalist Chinese Colonel (COL) Jack Young, like American Flying Tigers pilots, was commissioned as a U.S. Army Reserve officer.11 Fluent in Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, Korean and several Asian dialects, Young was commissioned in the Adjutant General Corps and assigned as aide-de-camp to Lieutenant General Joseph W. Stilwell in the China-Burma-India Theater. Afterwards, while serving with the U.S. Military Mission to China, Captain (CPT) Young met the leading Chinese Communists, Mao Zedong, Chou En-lai, and Kim Il-Sung from Korea.12

As interpreter/aide for General George C. Marshall during his postwar China mission, Major (MAJ) Young became friendly with COL Laurence B. Keiser, who became 2nd Infantry Division commander.13 When war broke out in June 1950 and the 2nd ID was alerted for Korea, Major General (MG) Keiser asked AG Major Young to join his staff as the Deputy G-2. His experiences in Asia, language skills, and cultural background made Young a valuable asset.14

MAJ Jack Young, after assuming control of the South Korean police, began recruiting. He went looking for ROK soldiers sent home to recover from serious wounds, ex-soldiers and former policemen. Service with the Japanese was not a concern. While screening refugees MAJ Young was on the alert for military age males trying to infiltrate.15 Two of his early additions were South Korean Assemblymen, Kim Yong Woo, a University of Southern California graduate, and Kei Won Chung, who had a doctorate in literature from Princeton.16 These men proved to be very helpful with controlling the flow of refugees, assisting with their resettlement and helping to establish law, order, and local government.

On 2 September, Sergeant (SGT) Emmett V. Parker and CPL Joseph C. Howard, 2nd MP Company, working as refugee screeners, were told to abandon their posts if the enemy entered Yongsan. When the North Koreans did enter the city, the two MPs remained on post until the last American vehicle left and then they joined the infantry to help hold a nearby hill overlooking the city. When a counterattack began, the two MPs advanced with the infantry and cleared the area around their posts and returned to duty.17 SGT Parker was awarded a Silver Star for gallantry in action. This attracted MAJ Jack Young’s attention who decided to recruit him and Howard. After that he received a reluctant permission from LTC Becker, the Provost Marshal, to recruit CPLs “Moose” Thompson and Clark from the 2nd MP Company as well.18

Refugee problems grew steadily worse. More than 97,200 refugees had been collecting in Chang-do and the Division Artillery area. MAJ Young’s South Korean police were combined with the 2nd MP Company to clear the sector. A division raider unit (later named the Ivanhoe Security Force) was to be formed to sweep the Chang’ing to Chong road as soon as possible. “Ivanhoe” was the code name for the 2nd Infantry Division.19 Young commented: “Our main missions were to provide security for the Division Forward Command Post and major supply installations along the Main Supply Route (MSR) and to conduct battlefield surveillance and anti-guerrilla warfare.”20

An unusual task force (Headquarters Company, 9th Infantry Regiment, three 72nd Tank Battalion tanks, and B Battery, 2nd AAA Battalion) started patrolling the Yongsan-Chang’ing road the second week of September to eliminate the guerrillas. Simultaneously, the Ivanhoe Security Force conducted Operation SAND FLUSH to clear enemy patrols from behind division lines. Reinforced with two squads of riflemen, six MPs, an 81 mm mortar section, and an M39 armored personnel carrier (APC), the ISF captured a seventeen-man, officer-led patrol reconnoitering the Chang’ing area for an attack.21 This operation validated the ISF as an intelligence collecting raider unit.

“Major Jack Young of the Adjutant General Corps carries a burp gun instead of a pencil. He formed his raggle taggle army, mostly from South Korean policemen, after a full battalion of Korean Reds slipped through the American lines near Changnyong. The Reds had been raiding rear echelon American units. His group subsists on livestock, rice, and vegetables found in the abandoned fields. MAJ Young remarked: ‘It is like fighting the Chinese Communists all over again. We have killed thirty Reds and captured twenty so far. Today we killed three and captured seven. We have to keep the supply routes open.’”22

“ … We laughed at the commentary of ‘Seoul City Sue’ on the radio as well as the Communist loudspeaker broadcasts. We used their propaganda leaflets for toilet paper.” — CPL Joseph C. Howard

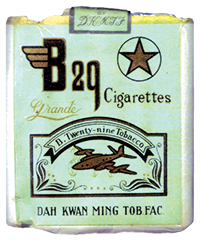

CPL Joseph Howard, one of the original four American non-commissioned officers (NCOs) with the ISF stated: “Our unit was made up of Korean officers and sergeants who were former Japanese soldiers and Imperial Marines. They believed in strict discipline and severe punishment. We wore assorted clothing. The Chinese jackets and mittens were very warm. We carried an assortment of American and Russian weapons which we had collected from the dead. We drove captured Russian vehicles and ‘appropriated’ U.S. Army Jeeps and trucks. Since our diet was heavy on rice, the Americans suffered from dysentery and jaundice. We laughed at the radio commentary of ‘Seoul City Sue’ as well as Communist loudspeaker broadcasts. We used their propaganda leaflets for toilet paper.”23

In the Eighth U. S. Army (EUSA) main effort (the Taegu-Kumchon-Taejon axis) on 16 September, 2nd ID was to drive directly west from its position. MAJ Young’s ISF was to secure Chang’ing and clear all enemy east of the town.24 Unbeknownst to the indigenous counter guerrilla unit the attack supported the Eighth Army breakout from the Pusan Perimeter after the Inch’on landing by the 1st Marine Division succeeded.25

The 2nd ID, having led the breakout and follow-on northward attack, was given a breather on 10 October just as signs of Chinese involvement began to appear. All units of the Indianhead Division were moved into reserve between Suwon and Yongdong-po. Relocation took four days. Personnel and weapons were inspected, shortages identified and filled, and the training emphasis was to integrate the South Korean KATUSAs (Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army) assigned to the regiments. Critiques of small-unit actions were conducted and tactical training reinstituted. For the first time since being alerted for Korea in July 1950, the 2nd Infantry Division could “sit-down” and take stock of itself and its situation. There was much to be done while the EUSA continued the attack. However, the imminent capture of North Korea’s capital produced another mission.26

On 16 October 1950, after the morning staff meeting, MG Keiser met privately with the G-2, LTC Ralph L. Foster, and his deputy, MAJ Young. Far East Command headquarters in Tokyo had ordered Eighth Army to organize an intelligence exploitation task force for P’yongyang “to secure and protect specially selected government buildings and foreign (Russian) compounds, until they could be searched for enemy intelligence materials.” The job was assigned to the 2nd Infantry Division. LTC Foster was to lead Task Force (TF) INDIANHEAD (2nd ID nickname) and leave as soon as possible.27

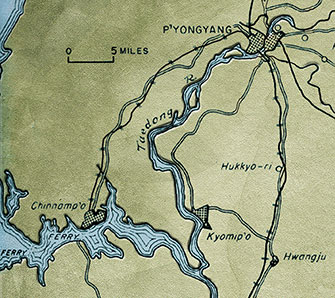

P’yongyang, the oldest city in Korea, had long been the country’s capital. It was about forty miles northeast of the Yellow Sea. When the war started, the population was approximately 500,000. The Communist capital sat astride the Taedong River, one of the largest in Korea, and which empties into the Yellow Sea. The major part of the city, containing the important government buildings, was on the river’s north side. A large, relatively new industrial suburb sprawled on the south side. The two bridges of the Pusan-Seoul-Mukden Railroad crossed at the industrial area. Two miles upstream from them was the highway bridge. All three bridges had been dropped by Allied bombing. At P’yongyang, the Taedong River was four to five hundred yards in width and the current was very swift, which made it a major obstacle to north-south military movements.28

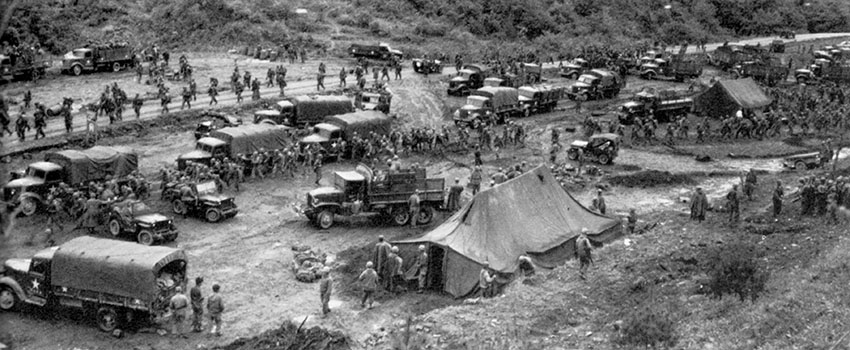

TF INDIANHEAD elements began assembling on 17 October at Chuoe-Myon where the 2nd Reconnaissance (Recon) Company was bivouacked. A reinforced K Company, 38th Infantry with seven officers was the largest element in seven 2 ½ ton trucks. Five M26 tanks, one M4 Sherman tank, and a halftrack came from the 72nd Tank Battalion. Two M24 tanks and another halftrack came from the 2nd Recon Co. The 2nd Combat Engineer Battalion provided a demolition team (one officer and 14 enlisted men). One doctor was accompanied by two medical aidmen. The 82nd AAA section consisted of one M16 and an M19. The MP Company sent a reinforced squad. CPT Allen Jung headed the Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC) agents and interpreters. ISF completed the motorized element which carried a basic load of ammunition and fuel.29

“ … I really wanted to be part of the Ivanhoe Security Force … MAJ Young and SGT Parker had warned my patrol about a machine gun nest while we were patrolling near the Naktong River … When we used a bazooka on that machine gun, he was impressed and I was hooked.” — CPL L. Carl Heesch

“I convinced my company commander that I should be assistant driver for CPL Parsons who was slated to drive a 38th Infantry deuce and a half. I really wanted to be part of the Ivanhoe Security Force,” said CPL L. Carl Heesch. “MAJ Young and SGT Parker had warned my patrol about a machinegun nest while we were patrolling near the Naktong River. When I overheard Major Young say something in Chinese, I responded in kind and explained that I had served in Tsingtao and Shanghai in 1948 and 1949. That was enough to convince me that I ought to get in his ‘irregular outfit.’ When we used a bazooka on that machinegun, he was impressed and I was hooked.”30

Second Lieutenant (2LT) John E. Fox, F Company, 38th Infantry explained: “There were six identically structured, platoon-sized (intelligence exploitation) operational elements. Each had a rifle squad, a light machinegun team, a 57 mm recoilless rifle team, and various specialists. My Team, #6, had two Korean guides from P’yongyang, LT Kang and SGT Kang. I had a medic, a radio operator, Nisei CPL Toshio Hasegawa as my messenger, two CIC agents, Clavin and another Nisei named Azebu, two engineer demolitions men, a Korean translator, LT Oh and a civilian interpreter, Pak II. One of my West Point classmates (Class of ’50), fellow Texan Harry Dodge, was in charge of another team. The K Company commander, CPT Warden, was the only one that had a map. The two CIC agents, Clavin and Azebu, jokingly explained that ‘CIC actually stood for ‘Christ, I’m confused.’ They actually ran the operation.”31

TF INDIANHEAD left the assembly area in three serials in the late afternoon of 17 October headed north. By 1830 hours, 18 October, two serials were in Sariwon and the other in Sinmak. Bucking traffic, the task force had managed to get ahead of the 5th and 7th Cavalry Regiments until the afternoon of 19 October when MAJ Young’s Jeep was blocked at Hokkyo-ri by one “fuming mad” MG Hobart R. Gay, the 1st Cavalry Division commanding general, who “shook his swagger stick at me demanding to know who we were. He didn’t care if our orders were signed by MacArthur himself. ‘Nobody was going to get ahead of the 1st Cavalry!’” recorded Young.32 The 1st Cavalry’s aggressive drive north had earned them the honor of being the first UN forces into P’yongyang. But, since there were no bridges or suitable crossing sites on the Taedong River for motorized equipment, MG Gay had to wait for his engineer boats.33

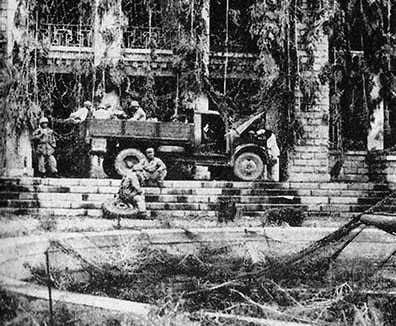

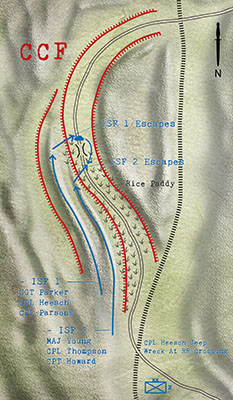

“Momentarily stunned, we halted long enough to gather our wits and plan our next move. While we were doing this, the ISF Koreans and Police scouts who had been dispatched to recon the neighborhood reported that they had encountered the ROK 1st Division preparing to cross the Taedong River to enter P’yongyang from the east. In the pouring rain I led Captain Hoe and a squad of ISF down a narrow, muddy trail, stepping around obvious mines, to see COL Paik Sun-yup, the ROK commander. He gave me a warm welcome. Paik, native to P’yongyang, spoke very good Chinese having served in Manchuria for many years. Some of his elements had already crossed the river and had met no resistance. He told me where the crossing sites were and generously offered me ten assault boats to get across the river. I gave CPT Hoe and his squad an SCR 300 radio, instructing him to cross and establish a base for us. I hurried back to bring SGT Parker and CPL Heesch and their two ISF platoons down to cross the river. By the time I had done this, CPT Hoe radioed that he had crossed with elements of the 15th Regiment, 1st ROK Division and they were outside the compound of Kim Il-Sung in the city,” recorded MAJ Jack Young.34

The rest of TF INDIANHEAD extricated itself from the 1st Cavalry column to go north. MAJ Young found the crossing sites just before dark. It would be 20 October 1950 before the remainder of INDIANHEAD entered the city from the northeast as the 1st Cavalry came in from the southeast.35 Thus, the ROKs and ISF get credit for being the first UN forces into the capital … the day before the 1st Cavalry.36

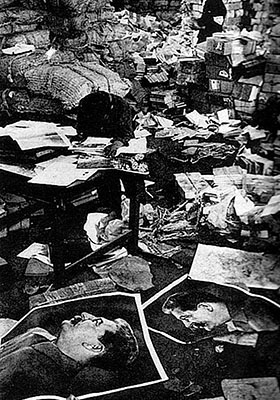

“The ROKs had no plans to secure the North Korean capitol grounds which encompassed the palace of Kim Il Sung. SGT Parker split our ISF Koreans into two groups and we headed for the capitol grounds, securing police weapons found in abandoned stations. We moved right into the grounds, collected the civilian employees standing about to put them under guard, and then systematically searched the three main buildings. Inside the buildings it was dead quiet and they were rather ghostly. Parker and I each acquired a North Korean flag. There were two large busts in Kim’s office: one of himself and the other of Stalin. On the wall along the stairs there was a ‘much bigger than life’ portrait of Kim Il Sung,” said CPL Heesch.37

Locating the whereabouts of American Prisoners of War (POW) was an additional TF INDIANHEAD mission. “After some questioning the civilian workers revealed that the American POWs had been moved the day before. When we asked about MG Dean, (MG William F. Dean, 24th ID commander, had gone missing in action in July 1950), they knew nothing. A third small building in the rear served as a commissary and was filled with booze, six crates of champagne, and cases of caviar and chocolate. It was in there that SGT Parker found six Browning 12-gauge semi-automatic shotguns,” said CPL Carl Heesch. “Then, we started roaming around the city.”38

“ … The only evidence of POWs that remained was a blackboard in one of the class rooms that still had a list of American names in chalk … ” — SGT Emmett V. Parker

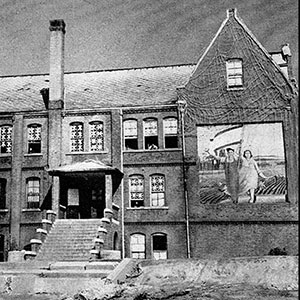

“MAJ Young had told us to look for MG Dean and the American POWs that had been moved north to P’yongyang when the Eighth Army broke out. They were allegedly held in a school in the capital. We did find the school and a caretaker confirmed that the POWs had been held there, but they had been put on railcars a few days prior going north. The only evidence of POWs that remained was a blackboard in one of the class rooms that still had a list of American names in chalk. We traced the route supposedly used by the POWs but only found a couple of American GIs and an Air Force pilot who had slipped away during the night movement and an elderly sick American priest who had been abandoned because he could not keep up,” said SGT Emmett Parker.39