DOWNLOAD

In the predawn hours of 25 June 1950, more than 100,000 North Korean soldiers crossed the 38th Parallel to invade South Korea. The move by the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA), a force possessing tacit and material support from the Soviet Union and combat experience gained during the 1940s Communist takeover of China, instantly turned the Cold War hot. The immediate cause of the 1950 North Korean invasion can be linked to the closing days of WWII, as two emerging superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, struggled to exert their influence over the Far East. The long-term causes of the Korean War, however, have much deeper roots, and are a product of centuries of interaction between Korea and its neighbors – China, Japan and Russia.

A Land of Contrast

A small but beautiful country, Korea occupies a peninsula separating the Sea of Japan from the Yellow Sea, only twenty-five miles northwest of Japan across the Tsushima Straits. Its northern border with China is the Yalu (Anmok) River, and with the former Soviet Union, the Tuman (Tumen) River. About the size of Utah, Korea shares the same approximate latitude as San Francisco, CA, Wichita, KS, and Philadelphia, PA, but has a much more varied climate. Summers are generally hot and humid, with average July temperatures of 80° F (27° C). Winters are long and bitterly cold, with temperatures in January averaging 17° F (-8° C). Icy winds sweeping down from Manchuria make it feel much colder. The monsoon season, which lasts from late June through mid-August, turns normally dusty lowlands into seas of mobility-hampering mud.1

Korea is between 90 and 200 miles wide, and between 525 and 600 miles in length, with a 5,400 mile-long coastline. Over seventy-five percent of the country is mountainous. Most of these mountains are in the northern Nangnim and Hamgyong sanmaeks (ranges). The tallest peak, Paektu-San [9,003 feet (2,744 meters)], sits astride the border with China. The Yalu and Tuman Rivers flow north of the northern mountains towards the west and east respectively. In the south, the T’aebaek (“Spine of Korea”) sanmaek dominates the eastern side of the peninsula, and is bisected by the Sobaek sanmaek running northeast to southwest. To the northwest, the watershed slopes towards the coast, and the Han River flows northeast through Seoul. These southern ranges also define the Nakdong River basin, which generally flows through agricultural plains found throughout the south and southeast. The western coast of the Korean peninsula has numerous offshore islands, as well as many natural harbors and waterways. The west coast tides, particularly at Inch’on, vary as much as thirty-two feet and greatly complicate coastal navigation and maritime commerce. In contrast, mountains that reach the very edge of the eastern coast emphasize the importance of ports like Hungnam, Wonsan and Pusan.2

Differences between North and South Korea extend beyond geography. There are stark contrasts in regards to resources, industry and agriculture. For much of their history, North and South Korea complemented each other and trade was active. By the end of WWII, the Japanese had concentrated most industry in the north, where hydroelectric dams and power facilities enabled the exploitation of gold, iron, tungsten, copper and graphite deposits. Mineral wealth was absent in the south. There, the population was chiefly agrarian. Rice, wheat, millet, corn, and soybeans were cultivated using centuries-old methods in the “breadbasket” region.3

Modern transportation was key to developing the Korean peninsula but the terrain posed a serious challenge. One major rail line, built by the Japanese in 1906, ran north from Sinuiju on the Yalu River, southward through P’yongyang, and eventually to Seoul. A second line joined at Seoul, linking the capital with Pusan on the southern coast. Feeder lines connected Seoul and P’yongyang to other regional centers. A branch to the South Manchuria Railway at Sinuiju linked Korea to Asia and the rest of Europe. During WWII, rail traffic supported the external needs of Japan and trade within Korea was nonexistent. After the war, this aging system deteriorated further due to a lack of resources and attention. A sparse road network followed the rail line routes. These narrow, gravel roads with sharp curves and light-duty bridges could not support heavy vehicles, further reducing interregional traffic.4

Korea and its Neighbors: Ancient to Modern

Discord between Korea and its neighbors, dating back thousands of years, is part of the region’s rich history and politics. Korea’s close proximity to Japan, and shared borders with China and Russia (later the Soviet Union) made it vulnerable to all three nations. Each left its imprint upon Korea, and all three, coupled with the post-WWII presence of the United States, were linked to the outbreak of war between a divided Korea.

Ancient Korea was originally comprised of numerous walled town-states. By the third century AD, three kingdoms dominated Korea: Paekche surrounding present-day Seoul, Koguryŏ in the north, and Silla in the central part of the peninsula. An alliance with China’s Tang Dynasty allowed Silla to unify the peninsula by 668 and introduce Confucianism and Buddhism to Korea. Under Chinese patrimony, the Silla Dynasty exercised autonomous control for three centuries until its replacement by the Koryŏ Dynasty in 918. Under consistent leadership of the Koryŏ (918-1392) and Chosŏn (1392-1910) dynasties, the consolidated Koreas flourished culturally, repelling attacks from the Khitans (920s), Mongols (1230-1270), Japanese (1592-1598) and Manchus (1620-1630).5

China allowed Korea to manage its domestic concerns, but controlled all foreign affairs. With China’s gradual decline in the mid-19th century, other nations sought access to trade with Korea. The United States, Great Britain, and Russia secured trade treaties in the 1880’s, but Japan remained the greatest threat to Korean autonomy, because it hoped to dominate the entire Yellow Sea region.6 The Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), effectively demonstrating Japanese martial improvements made since the Meiji Restoration, ended China’s dominion over Korea. The Treaty of Shimonoseki (1895) granted Korea total independence from China, but opened the way for Japan to gain control.7

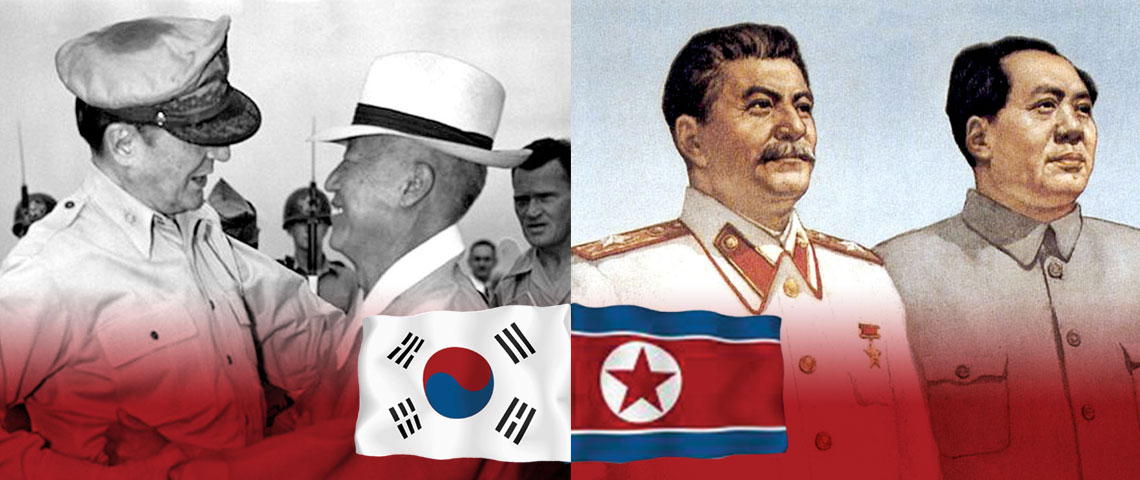

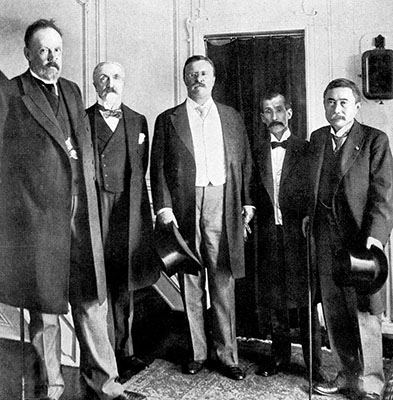

Czarist Russia challenged Japanese hegemony in Asia. When Chinese nationalists failed to end western influence during the Boxer Rebellion (1900), Russia moved troops into Manchuria and occupied northern portions of the Korean peninsula. Japan and Russia later agreed to jointly occupy Korea, dividing it along the 38th Parallel. The two unsuccessful invasions of Japan launched from Korea by Kublai Khan in 1274 and 1281, caused the Japanese to regard the peninsula as a “dagger pointed at the heart” of their country. Japan and Russia subsequently came to blows over the joint occupation of Korea in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905).8 Unable to achieve a decisive land victory at Mukden, the Imperial Japanese Navy delivered a deathblow to the Russian fleet at Tsushima. The Treaty of Portsmouth, brokered by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905, forced Russia to abandon Korea and recognize that the entire peninsula lay within a growing Japanese “sphere of influence.”9

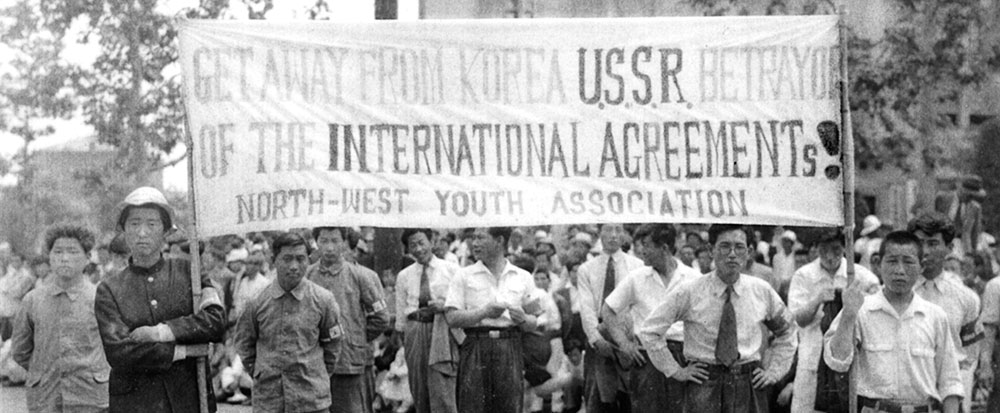

Korea became Tokyo’s colony for the next forty years. On 1 March 1919, American-educated Syngman Rhee and other Korean leaders led thousands of their fellow countrymen in peaceful demonstrations against the Japanese. The marchers read a proposed declaration of independence and carried a prohibited Korean flag. Outraged by the overt display of Korean nationalism, Japanese authorities cracked down unmercifully. Hundreds of thousands of Koreans fled the country or joined underground revolutionary movements. Between 1921 and 1937, Korean expatriates tried to secure foreign support for national independence. In the United States, the future South Korean President Rhee advocated democracy. Others like Kim Song-Ju (later Kim Il Sung) briefly led guerrilla groups against the Japanese in northern Korea before joining with Communists in China, who were supported by the Soviets during WWII.10

World War II and its Aftermath

Japan incorporated Korea into its “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” during WWII. Although the Korean population grew from twenty million to twenty-five million between 1930 and 1944, they suffered terribly during the war. Koreans faced Allied bombings, conscription into the Imperial Japanese Army, or work as forced laborers, as well as economic hardship and psychological strain at the hands of the Japanese. Korea’s natural resources, particularly its timber, supplied the Japanese war machine for almost twenty years.11