DOWNLOAD

Shortly after the main body of the 1st Radio Broadcasting & Leaflet Group (1st RB&L) arrived in Tokyo in early August 1951, the Far East Command (FECOM) adjusted its strategic Psywar priorities. Radio Tokyo program management was number one. Inherent in that mission was responsibility for Voice of the UN Command (VUNC) because broadcasting would originate from Radio Tokyo studios. Second Lieutenant (2LT) William F. Brown, II, the 1st RB&L Psywar officer at Kaesong, Korea, was the first UN line of defense against Communist disinformation and propaganda during the Armistice talks. His daily teletype reports served as the official UN statement on the status of negotiations.1 Restoring the Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) radio stations to full operation was the 1st RB&L second priority.2 Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Homer E. Shields, the Psywar group commander, functionally realigned his staff, “dual-hatted” the most experienced officers, and pulled in talent from his subordinate units to begin addressing FECOM priorities.

Organizationally the 4th Mobile Radio Broadcasting Company (MRBC) had the majority of assets in the 1st RB&L for radio broadcasting missions in Japan and Korea. The pressure to field the 1st RB&L, get officers and soldiers Psywar-trained, and deploy overseas left little time to practice collective unit tasks, solidify assignments, and develop work procedures. The internal restructuring had little impact on the soldiers because the 1st RB&L had a large number of WWII veteran lieutenants and captains whose leadership and management skills included professional writing, commercial radio, television, publishing, and advertising experience. Shifting priorities were taken in stride.3 The reshuffling was done while the soldiers settled into billets, got oriented in Japan, learned staffing procedures, created work areas, and became familiar with their duties.4

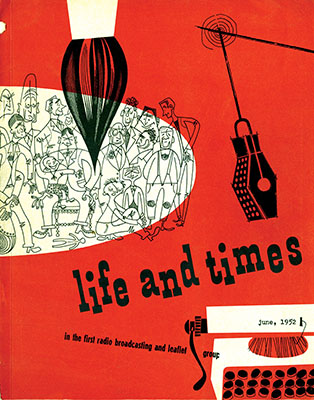

This article shows how the 4th MRBC adjusted to theater Psywar priorities in Japan and Korea and conducted “combat” training. The explanation shifts back and forth between Korea and Japan until mid-February 1952 when company headquarters relocated to Seoul. Veterans discuss their jobs, the challenges, and overseas duty. The reader will be kept current on soldier activities in Tokyo and Korea. Weekly 1st RB&L newspaper articles from The Proper Gander, contemporary commercial news articles, veteran interviews, U.S. Army FMs and TMs (Field Manuals and Technical Manuals), U.S. Army General School, Psywar Division POIs (Programs of Instruction), official documents, the USNS General Brewster personnel manifest, and the unit “yearbooks” (1952 and 2002) provided invaluable source material. Once in Japan, the 1st RB&L quickly adjusted to its wartime requirements.

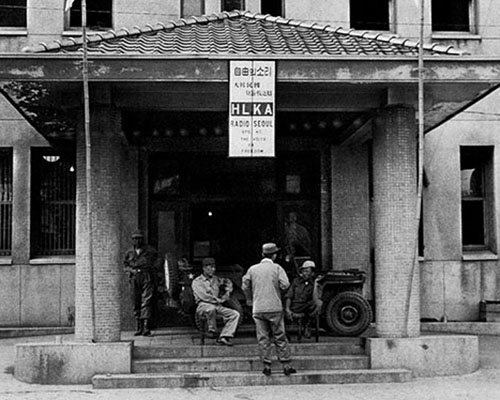

Radio stations that shared air time.

Radio stations that shared air time. HQ 1st RB&L elements.

HQ 1st RB&L elements. 1st RB&L 5kw moble transmitter.

1st RB&L 5kw moble transmitter.  1st RB&L programming detachment.

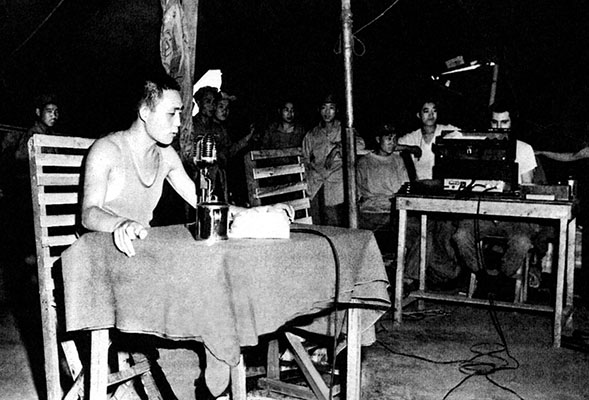

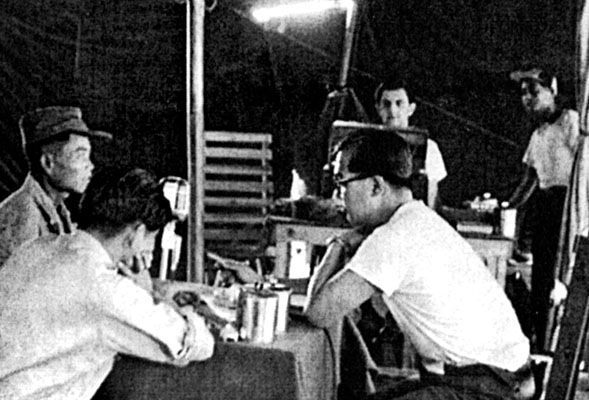

1st RB&L programming detachment. Special news correspondent for the 1st RB&L covering the armistice talks.

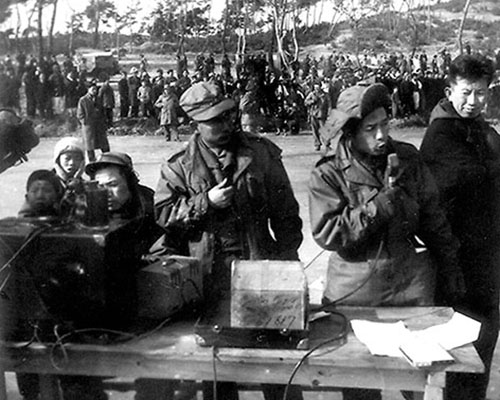

Special news correspondent for the 1st RB&L covering the armistice talks. Town or city where a 1st RB&L detachment, radio station, or leased transmitter was located.

Town or city where a 1st RB&L detachment, radio station, or leased transmitter was located. HQ of the national radio network (Korean Broadcasting System) and the major Psywar studios in the country.

HQ of the national radio network (Korean Broadcasting System) and the major Psywar studios in the country.