SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

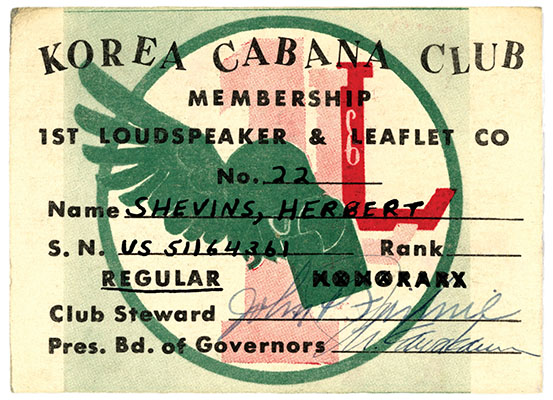

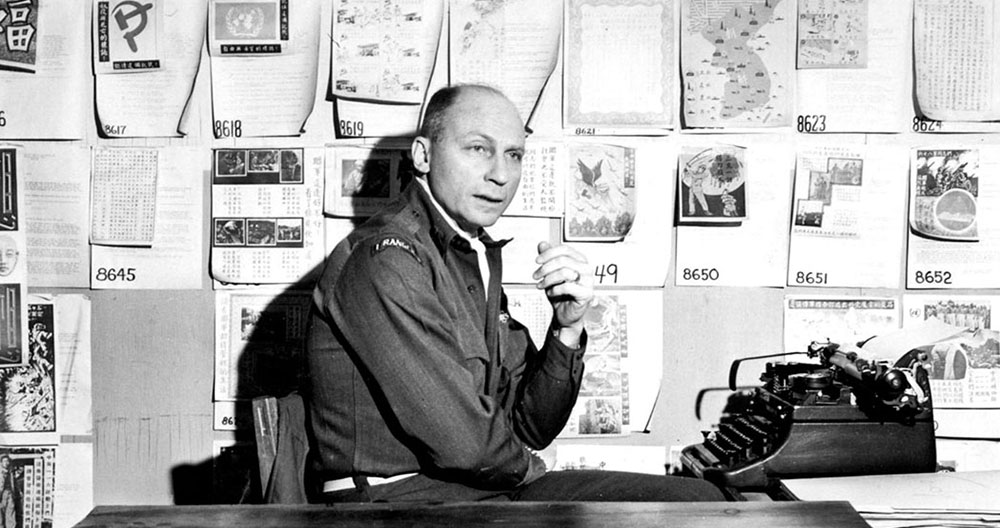

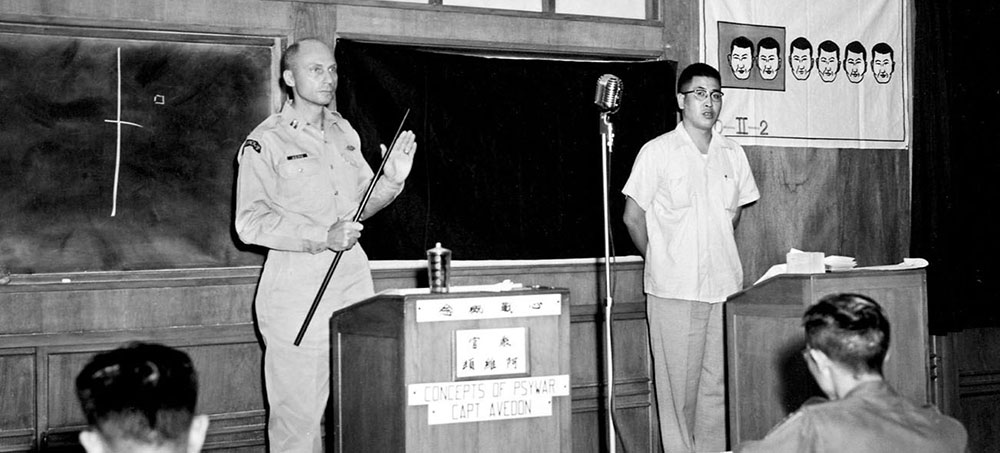

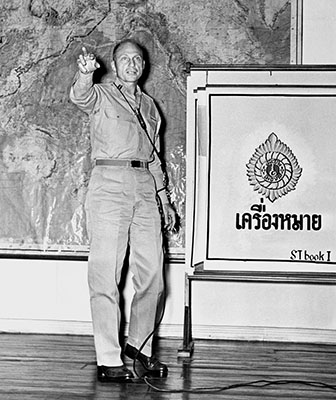

On 12 April 1952, Captain (CPT) Herbert Avedon assumed command of the 1st Loudspeaker and Leaflet Company (1st L&L), the only tactical Psywar unit in Korea supporting the Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA). At the time, CPT Avedon was one of the more seasoned company-grade Psywar officers in the U.S. Army. The WWII veteran was able to use his knowledge to improve tactical Psywar operations, and through that, the effectiveness of the 1st L&L. In addition, Avedon had a considerable background in other Special Operations units. During WWII he served in both the Rangers and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). His experience illustrates the type of veteran drawn to Special Operations during its rebirth in the Korean War and who continued to influence its organization afterwards.

Avedon first entered the Army National Guard in May 1933 and served until February 1934.1 He did not enlist in the regular U.S. Army until 30 September 1940, after which he completed his basic training as an infantryman at Vancouver Barracks, Washington. The nearly bald thirty-four year old earned the nickname “Curly.” His first posting was to the Panama Canal Zone to serve with the 33rd Infantry Regiment. He later referred to this assignment as being in a “jungle-bound 8-ball unit.”2 He then served in the 16th Pursuit Group until 2 December 1942 when he returned to the United States.3 On 23 March 1943 Avedon graduated from Officer Candidate School at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, with a Reserve Army commission in the Signal Corps and a specialty in codes and ciphers. After a brief stint in signals intelligence in the Pentagon, he transferred to the 849th Signal Intelligence Company in North Africa (April to July 1943) supporting Fifth Army. It was there that he joined the 1st Ranger Battalion as its signal officer. Avedon served with the unit in Sicily and Italy during the Salerno and Anzio campaigns.4 In this, its last campaign, the 1st Ranger Battalion was part of the 6615th Ranger Force (Provisional).

Specifically formed for the Anzio invasion to help the Allies consolidate their beachhead and lead the advance to Rome, the 6615th included the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Battalions, 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, the 83rd Chemical Mortar Battalion, and H Company, 36th Combat Engineer Battalion. On the night of 29-30 January 1944, the 1st and 3rd Rangers led the attack towards Cisterna, supported by the 4th Ranger Battalion.5 The Germans quickly recovered from the surprise of the night attack and counterattacked in force, surrounding the two attacking Ranger battalions, to kill or capture nearly 800 Rangers. The Germans repeatedly beat back the 4th Ranger Battalion attempts to relieve the two encircled battalions.

After Cisterna, the Rangers in Italy were combat ineffective.6 On 26 March, the 4th Ranger Battalion was disbanded and its soldiers reassigned. Long-term Ranger veterans returned to the United States to reconstitute a new unit while those without sufficient combat time became replacements for the First Special Service Force.7 Returning to the United States on 6 May 1944, First Lieutenant (1LT) Avedon received an assignment to the 4th Ranger Infantry Battalion being formed at Camp Butner, NC. The OSS recruited him there on 6 October 1944 based on his combat experience, maturity, and technical skills.8