DOWNLOAD

This article describes one of the 4,445 North Korean partisan actions taken against Communist forces during the Korean War.1 It is written from the guerrillas’ perspective to provide insight into their combat engagements; events that were rarely captured in the conventional military historical effort. This viewpoint is important as it allows soldiers today to better understand how these partisans operated behind enemy lines and the limitations and constraints they overcame to remain successful on the battlefield. It reveals the conditions that affected their planning and the conduct of their combat actions. It also shows the importance of the guerrilla’s interactions with friends and neighbors who clandestinely supported their activities.

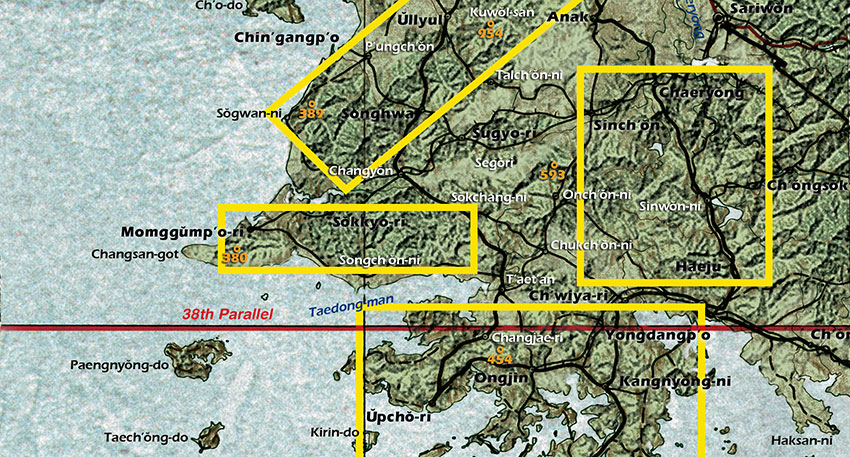

One representative guerrilla action involved Kim Yong Bok, the leader of Donkey 3, a partisan unit operating on the West Coast of North Korea. Kim had been conscripted during World War II and later served as a lieutenant in the Japanese Army in Manchuria, China. After the surrender of Japan in August 1945, Kim worked as a clerk in South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs before returning to his family home in Changyon, Hwanghae Peninsula, North Korea, in late 1946. At that time Communists began seizing private property and Kim’s family lost their farm. When North Korea’s forced conscription policy started in 1947, he hid in the mountains to avoid being drafted. Many other anti-Communists were doing the same, with the help and assistance of their families and sympathizers.2

As UN troops approached his village in October 1950, Kim Yong Bok and his friends emerged from the mountains, formed a village security force, and Kim became the chief of the area’s police detachment. When the UN troops withdrew from that region in December, Kim and his men again fled to the hills to avoid capture and probable execution. Like before, sympathetic villagers provided food and supplies for the exiles and also assisted them in escaping the area. One farmer told him the location of a ‘wiggle’ style (small, one-oar) fishing boat that they had recently fixed for the Communists. Accompanied by a fellow refugee, Kim secured the boat, paddled to the nearby island of Cho-do, and joined a guerrilla unit forming there. After meeting with Major (MAJ) William A. Burke, the commander of the LEOPARD guerrilla base on Paengnyong Island, Kim became the leader of the partisan Donkey 3 unit.3 This extract from a contemporary interview of his experiences sheds light onto how the Korean partisans operated during the war.

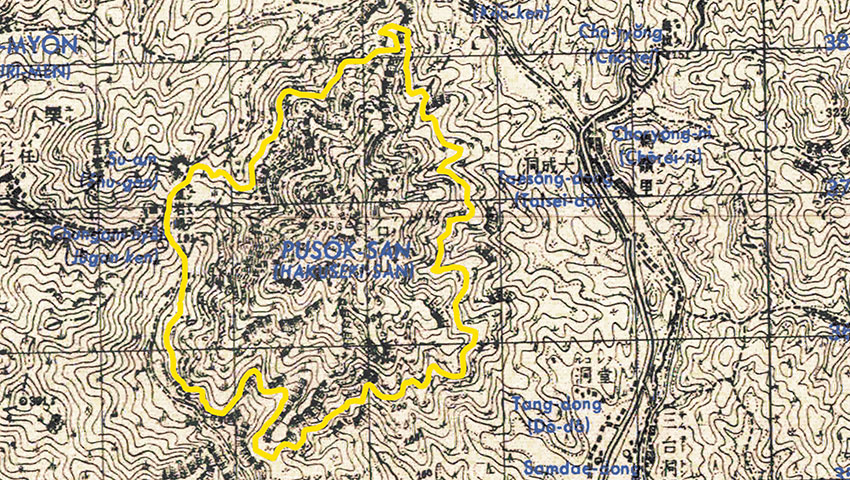

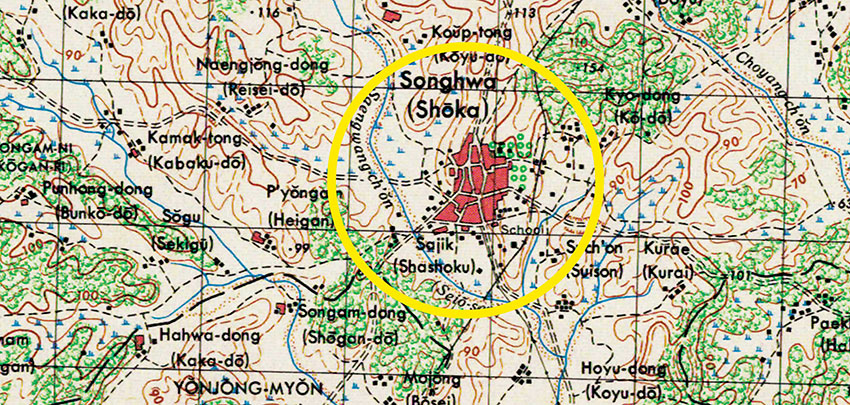

Kim described one representative operation in early 1952 undertaken both to inflict casualties on the enemy behind its own lines and to demonstrate the power and intent of the partisans to the people of the region. At that time, Kim’s unit maintained a small, semi-permanent forward base deep in a remote, mountainous part of the Hwanghae Peninsula. His guerrillas were supplied and fed by sympathetic villagers because the Communists were tightening their grip on the farmers in the region. Those same local farmers also provided Kim’s men with a good situational awareness of enemy dispositions and movements in the area, giving Donkey 3 some degree of security and also informing them of probable enemy targets. In this particular action, Kim acted on tips from sympathetic supporters and made plans to attack a police station and the town hall in the village of Songhwa, about nine kilometers away. He wanted to destroy the Communist Party infrastructure in that township and kill the North Korean-installed government officials. After finishing his preliminary plan and rehearsals, Kim left his remote camp on Pak-sok Mountain (or Pusok-san) with eleven other guerrillas and patrolled overland toward his target.4

Locals had passed him information regarding enemy patrols and checkpoints in the surrounding countryside that helped Kim’s unit avoid detection during their movement. Dressed in a mix of civilian clothes and North Korean uniforms, and carrying a varied collection of weapons, the party travelled mostly at night, hiding themselves by day. They crossed several streams and open areas on their way to their target, taking care to avoid raising any alarm from their movement. Enroute to the objective, the guerrilla chief also hoped to confirm details on the presence and actions of Communist Party and North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) members at Songhwa. Nearing the village, Kim’s group encountered a hunter, a resident of the village who was not personally known by any of his party. Seeking both to confirm details regarding the enemy situation and to prevent the unknown man from betraying their location, Kim’s men seized him and questioned him for the information they needed. Kim recalled that “I captured the hunter and [told him] that I was going to shoot him because he was a Communist. He said he was not a Communist and to please spare his life. So I said that I would spare his life.” Not surprisingly, the hunter provided Kim with the information about the enemy disposition, divulging enough to allow the guerrilla to complete his plan of attack.5

“I captured the hunter and [told him] that I was going to shoot him because he was a Communist. He said he was not a Communist and to please spare his life. So I said that I would spare his life.”— Kim Yong Bok, the leader of Donkey 3

With the lives of his men at stake, the cautious partisan leader also took steps to verify the information provided by the hunter. He confirmed its accuracy by comparing it with reports gained from other sources. He “had one radio operator [in Donkey 3] who was quite familiar with the area and what the hunter said [matched] what the radio operator was saying.” Furthermore, “To make sure my information was accurate, I called on the chief of the ROK Youth Group [that] had been organized when the UN Forces had advanced into the area. His name was Won Byong Hun, [still living] in the village at that time.” Mr. Won confirmed that the information given by the hunter was accurate. In addition, Won and another trusted man joined Kim’s unit for the attack, raising the total number of raiders to fourteen.6

“I finally reached my destination. There were four [separate targets] that I wanted to hit. One was a police station detachment. One was the Communist Party Myon [township] Detachment office, another was the myon office [town hall], and the fourth was where a platoon of enemy [troops] stayed in that town.” Kim allocated his forces to cover three of the targets, discovering through his sources that the Communist Party office was empty at that time. And after deliberating on the number of guerrillas he had on hand against the small garrison, Kim “decided to cancel my raid on the enemy platoon location because I had too small a number of men to attack the whole platoon.” Instead he formed a security element and tasked it to establish a blocking position “in case [the platoon] came to reinforce the police station detachment, which was my main target.” Kim also took other measures to prevent the enemy platoon from effectively reacting to his attacks on the police station and myon office that will be covered later.7

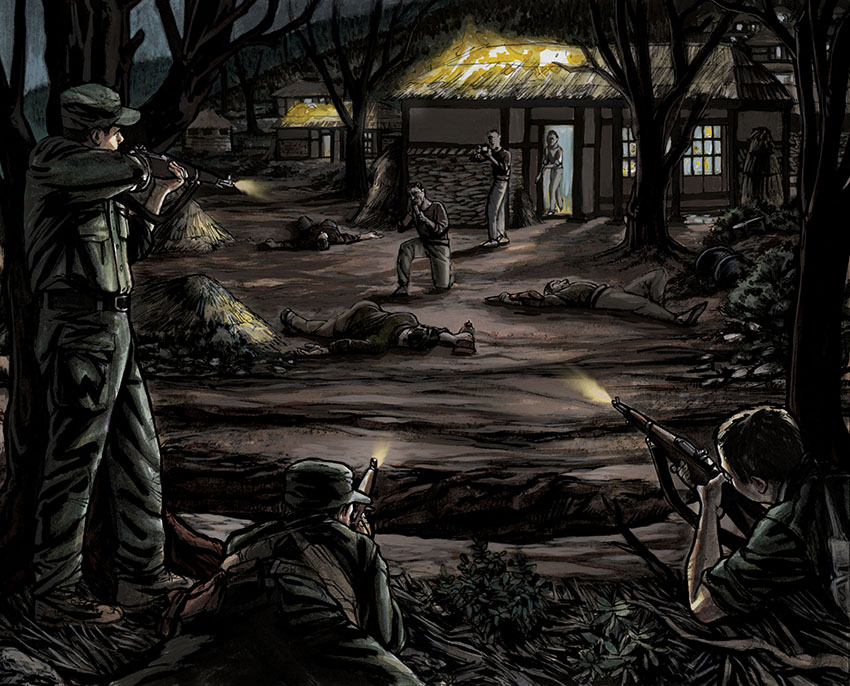

To maintain command and control, Kim personally led the group assigned to attack his primary target at the police station. Moving into their attack positions near midnight, Kim observed that “Six policemen were in the station and many people were gathered” there. Kim emplaced his men, taking care to utilize some large trees around the police station that provided excellent cover and concealment. “At that time our equipment was three carbines, six M1s, one PPSH [Russian sub-machine gun], one Russian light machine gun, … one hunting gun and one rifle.” One man carried grenades. Now in their firing positions, the guerrillas stood ready until five minutes after midnight, the specified time for the attack.8

“A volley fire took place when three rounds were fired by me as the signal to open fire. Immediately, the windows of the enemy police station detachment were broken and some of the enemy policemen were shot on the spot.”— Kim Yong Bok

Kim described the action: “A volley fire took place when three rounds were fired by me as the signal to open fire. Immediately, the windows of the enemy police station detachment were broken and some of the enemy policemen were shot on the spot.” Kim’s men seized the station, killing most of the police outright and capturing a few. Behind the police station the guerrillas discovered an air raid shelter that the police had converted to a makeshift jail holding thirty-two men, women, and children detained by the Communists. In some of those cases the Communists had incarcerated whole families for the ‘crime’ of being suspected of having sympathies for the guerrilla cause. Kim’s men freed the prisoners. In addition, Kim’s guerrillas killed eight policemen, and gained “seven rifles such as the Japanese 99 and the Japanese 38, and captured documents and papers.”9 The raid was off to a good start.

On the second objective, synchronizing their attack with Kim’s assault on the police station, the second combat element opened fire on the myon township hall. That second action produced comparable results: the guerrillas killed a North Korean first lieutenant, the county’s Communist “culture propagandist,” and six other members of the town’s oppressive governing body who had been living in the building. Although one high value target, the chief of the local Communist Court of Law, managed to escape in the confusion of the attack, the partisans had essentially succeeded in decapitating the township’s Communist government infrastructure with their bold, two-pronged attack.10

Successful raiders always plan carefully for their withdrawal. To prevent the town’s garrison platoon from effectively reacting to his men’s assault, the resourceful guerrilla chief incorporated a deception plan into his exfiltration. His men had earlier primed several blocks of TNT, not with the intent of destroying anything, but rather “just to make a big noise.” To simulate that the guerrillas were armed with heavy weapons, Kim’s men also had scattered some expended 40 millimeter brass cartridges over the path that the reacting platoon would take. The deception plan had an audible element as well. “When I ordered the machine gun to fire … I said, ‘Heavy machine gun, fire!’ To the carbine men I said, ‘Light machine gun, fire!’” Before his men lobbed grenades or explosives at the enemy, Kim shouted “Mortar, fire!” at the top of his lungs so that the enemy could also hear his command and the resulting explosion, and therefore mistakenly believe that the partisans were stronger and more numerous than they actually were. Although these tricks might not fool veteran ears, they confused the less experienced conscripts such as those garrisoning rear areas.11

As Kim recalled, “I burned the myon office building completely down,” creating confusion and fear throughout the village. “While we were shooting the enemy, blasting the TNT, throwing hand grenades, firing carbines and light machine gun, and shouting the false orders, the one enemy platoon [reacted to our attack and moved] to reinforce the myon office. When they heard the false orders they [fell] back and took up defensive positions, which was done in vain because I did not attack them.” Instead, taking advantage of the resultant confusion, Kim’s men successfully disengaged and withdrew from the area, aided by the several hours of darkness remaining and the keen knowledge of the terrain resident in his men who were born and raised in that region. The partisans employed their intimate familiarity with the area to return to their base of operations undetected. Later, in addition to passing on his report of the action, Kim proudly conveyed that “I had no casualties” in the mission.12

“While we were shooting the enemy, blasting the TNT, throwing hand grenades, firing carbines and light machine gun, and shouting the false orders, the one enemy platoon [reacted to our attack and moved] to reinforce the myon office. When they heard the false orders they [fell] back and took up defensive positions, which was done in vain because I did not attack them.”— Kim Yong Bok

For months after this action Kim and the men of Donkey 3 conducted similar small-scale raids and ambushes, launching them from either the relatively secure island base at Cho-do, or from his forward camps located in the mountains of North Korea.13 By his own account, Kim’s unit “participated in [six] surprise raids [and he personally] led ambushes in more than twenty” locations throughout the Hwanghae Peninsula. During an eight-month period, his men reportedly “captured about 55 Russian rifles, 12 PPSH’s [submachine guns …], 130 oxen, [and] captured approximately 150 bags of rice, including some grain” that nicely supplemented their rations. Donkey 3 also “induced about 23 enemy to surrender …, killed approximately 280 [enemy troops], captured four sail junks, destroyed fourteen buildings …, and rescued refugees and loyal youth out of the [Communist-held] mainland.”14

Kim Yong Bok served as the leader of Donkey 3 until February 1952, when he became the commander of the Honor Guard at LEOPARD Base on Paengnyong Island. In that capacity he received two months of additional training and then performed bodyguard and security functions for Major Leo McKean, commander of the base. In addition, he also trained his men in the skills needed to continue as a viable military threat to the enemy.15

Accounts of guerrilla combat actions such as this provide valuable insight into how guerrilla forces operate. This single example illustrates guerrilla application of key principles: the importance of gaining the most current information available to support the planning process; the value of surprise; and the utility of developing a creative deception plan to confuse the enemy and facilitate a safe withdraw from the objective area. By studying the combat experiences of guerrilla leaders like Kim Yong Bok, modern Special Operations soldiers can better appreciate the practical problems faced by indigenous irregular military leaders in the conduct of unconventional warfare. They will also realize more clearly the strengths and limitations of guerrilla fighters. That understanding is especially critical for soldiers tasked to train and advise similar units.