DOWNLOAD

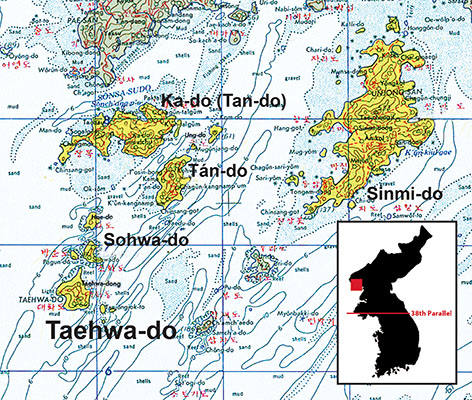

This article provides greater detail on the events of the fight for the guerrilla-held northwest islands. The ‘Battle of Taehwa-do,’ as some books refer to it, reflected the new interest that Far East Command (FEC) placed on keeping those islands under friendly control. It reveals how the important those islands were for FEC elements that used them as a base for gaining early warning and intelligence on the enemy. As seen in other articles in this issue, possession of the northwest islands provided the FEC with safe areas where rescue assets like helicopters and boats could be employed to recover downed pilots or aircrew.1 As a result of the fight for control of those islands, FEC reorganized its forces to better defend the islands in the future and island defense became an implied task for all guerrilla units.

On the night of 5 November 1951, Chinese Communists landed on the guerrilla-held islands of Ka-do and T’an-do, only forty miles southeast of the mouth of the Yalu River. Supported by nine Tu-2 Bat bombers and sixteen prop-driven La-11 Fang fighters backed by MiG-15 jets, the Communists quickly drove the guerrillas off the islands, forcing them to flee ten miles in fishing boats to their main base on Taehwa-do. Little more than a week later, on 15 November, eleven enemy bombers hit friendly positions on Taehwa-do in a daylight attack to soften them up for an assault. The commander of Task Force (TF) TAEHWA-DO, British second lieutenant (2LT) Leo S. Adams-Acton (earlier on Operation SPITFIRE), quickly discerned the pattern and directed his guerrillas to improve their defensive positions. Adams-Acton also reported the developments to his commander at TF LEOPARD on Paengnyong Island, requesting naval gunfire and air support assets to help him defend against the impending attack. The British Destroyer HMS Cossack (D-57) proceeded to the island and Air Force planners prepared their own surprise for the Chinese.2

Beginning on 16 November, the Chinese Air Force bombed Taehwa nightly, methodically working over the guerrilla positions. When the Cossack arrived, it provided Adams-Acton with two British Royal Marine naval gunfire spotters and radios to efficiently call and adjust the ship’s four 4.5-inch guns from Taehwa-do. Adams-Acton then planned and executed a raid on Ka-do on the night of 24-25 November to keep the Communists off-balance. The raiders, backed by accurate naval gunfire from the Cossack, swiftly landed and caught the Chinese by surprise. The guerillas inflicted damage to the enemy and carried away several prisoners who confirmed the enemy’s intent to seize Taehwa-do.3

While the guerrillas were raiding Ka-do, Chinese troops landed on nearby Sohwa-do (a small island northeast of Taehwa-do) and quickly pushed the men of Donkey 13 off the tiny island. The survivors withdrew to Taehwa-do, where Adams-Acton fitted them into his defensive scheme. Meanwhile, nightly Communist airstrikes by up to a dozen Chinese Tu-2s continued.4 Things were rapidly coming to a head in the northern islands.

The main Chinese assault on Taehwa Island began just before midnight on 29 November. Small folding wooden boats transited between the islands and disgorged Chinese assault troops in the initial waves, followed closely by a sampan fleet fitted with mortars and rockets. Once ashore, the disoriented but determined Communists fought their way inland as Adams-Acton’s men called and adjusted naval gunfire into the massed formations. Fighting continued throughout the night and into the next day. Meanwhile, the Far East Air Force planned a trap of its own in what would become one of the largest air battles in the war.5

When the attacking Chinese soldiers called for a daylight air strike against the guerrillas, a group of twelve Tu-2 bombers and sixteen La-11 fighters left their bases north of the Yalu River and sprinted toward Taehwa-do. But this time the Americans had anticipated that action and were waiting to pounce. As the bombers crossed into North Korean airspace and proceeded to their target, a prepositioned group of thirty-one American F-86 Sabre jets dropped out of the clouds behind them. Calling “Come down and get ‘em,” the mission commander, Air Force Colonel (COL) Benjamin S. Preston, Jr., led the attack on the unsuspecting Chinese aviators.6 “Everybody was going wild,” one F-86 pilot reported. “The sky must have been chock-full of lead. Planes were smoking, there were splashes below, and radio fight-talk was intense. It was the damnedest violent action I ever saw – kill-or-be-killed destruction!”7 Eighteen Communist MiG-15s soon joined the fight but could not stop the slaughter. In the end the Air Force shot down eight Tu-2s, three La-11s, and one MiG-15, damaging and scattering the rest. The Chinese Air Force never again attempted a daylight bombing raid in Korea.8

On the ground, the Chinese fought hard for the island even as their negotiators returned to the table at Kaesong and settled on a line of demarcation that curiously avoided any mention of the northwest islands.9 Adams-Acton and his men put up a determined stand backed by occasional air support and responsive gunfire from two destroyers, the Cossack and the HMS Cockade (D-34). His two British naval gunfire spotters moved along the lines, accurately adjusting deadly fires onto the massed enemy. Yet despite their losses, the Chinese steadily pushed the guerrillas into a pocket on the south end of the island.10

Finally, just after 0200 hours on 1 December, the island fell. Guerrillas fled the island by boats, rafts, and even walked the reefs south as far as they could go to avoid the Chinese. In the final stages of the fight Adams-Acton, two British naval gunfire spotters, and American Sergeant First Class Charles B. Brock, Jr., were trapped in a bunker and could not evacuate. They were captured and sent to a North Korean POW camp. 2LT Adams-Acton was later executed by North Korean guards while escaping a month before the other three were repatriated during Operation BIG SWITCH (August 1953).11

The guerrillas had valiantly fought for the islands. FEC ordered them to be retaken. Within a month the guerrillas had captured Taehwa-do and its outlying islands. This time the guerrillas held it for a year before evacuating it as part of the Armistice deal. But the temporary loss of Taehwa-do and the northwestern islands led to another effort to reorganize Army guerrilla operations.