ABSTRACT

During Operation JUST CAUSE, one 96th Civil Affairs (CA) Battalion officer received a particularly challenging mission. Despite having no experience in project management or refugee assistance, Company C commander, Major Richard M. Cheek, oversaw the creation of a housing facility for 2,500 displaced civilians (DCs) in just two weeks. The major accomplished his difficult mission by working ‘by, with, and through’ local and inter-agency partners.

TAKEAWAY

- Finding effective Inter-Agency and host nation partners was critical to success for a CA officer with no previous experience in project management or DC operations.

- MAJ Cheek’s project management at the Albrook facility ensured that the housing, sanitation, and medical needs of thousands of DCs were satisfactorily met.

- The successful effort allowed the 96th CA to turn DC operations over to other partners and disengage from Panama.

SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

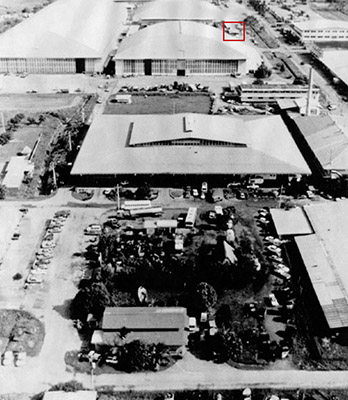

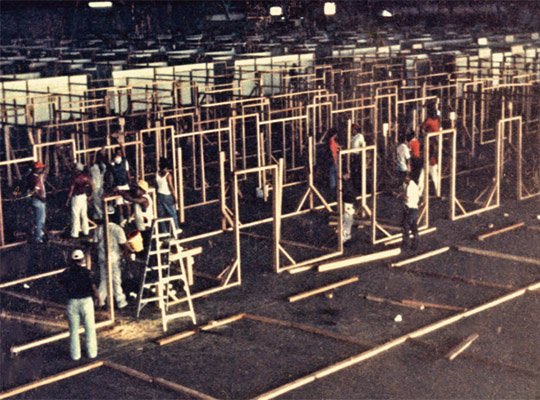

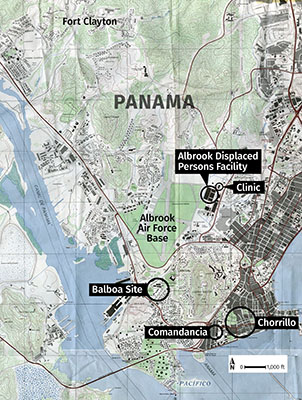

On the morning of 13 January 1990, approximately 2,500 Panamanian displaced civilians (DCs) arrived by bus and disembarked outside the entrance to Albrook Air Force Station. The DCs, whose homes had been destroyed during the early hours of Operation JUST CAUSE, initially found refuge at the Balboa High School, but had to relocate so the school could reopen for classes. Major (MAJ) Richard M. Cheek, Commander, Company C, 96th Civil Affairs (CA) Battalion, oversaw the conversion of a former Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF) hangar into a new temporary housing facility in just two weeks. This article briefly explains the situation that led to MAJ Cheek’s mission, and how, as the project manager, he successfully worked through local, interagency and non-governmental organization (NGO) partners to accomplish this difficult task.

On 20 December 1989, U.S. forces launched Operation JUST CAUSE to remove Panamanian dictator Manual Noriega from power. Three teams, of four to three men each, from Company A, 96th CA, which was focused on Latin-America, were attached to units of the 75th Ranger Regiment for their assaults at the Torrijos-Tocumen Airport Complex and Rio Hato.1 The rest of the 130-man 96th CA Battalion had not been scheduled to participate in the invasion. Planners had not anticipated how quickly they would have to implement post-combat stabilization efforts, under the civil-military operations plan dubbed BLIND LOGIC. That realization set in early on 20 December when U.S. Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) Commander, General (GEN) Maxwell R. Thurman, told Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, GEN Colin L. Powell, that no CA units were “available in the theater to support my mission requirements.”2 GEN Powell immediately ordered the 96th CA Battalion (-) to deploy to Panama. The bulk of the 130-man unit left Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and arrived at Howard Air Force Base, Panama, on 22 December. Once in Panama, Joint Task Force (JTF)-South tasked the 96th CA with a variety of on-the-spot situational missions and to provide teams to tactical units throughout the country.

One key but unplanned mission the 96th CA received was to run an impromptu DC facility located at the Balboa High School. In the course of the early fighting for the PDF headquarters, La Comandancia, a fire raged through packed shanties in the nearby poverty-stricken neighborhood of El Chorillo. With nowhere else to go, thousands of homeless Panamanians squatted on the Balboa High School grounds, threatening an unanticipated potential humanitarian disaster. To prevent this, ten soldiers from Company D, 96th CA Battalion administered the facility and solved problems concerning sanitation, food distribution, housing, and medical issues. While most of the DCs found housing with family or friends, some 2,500 remained when the facility was scheduled to close so the Balboa High School could reopen for classes on 16 January 1990.3

MAJ Richard M. Cheek had been on Christmas leave in Indiana when JUST CAUSE began. As the commander of Company C, operationally oriented to the Middle East, neither MAJ Cheek nor the 96th CA Battalion leadership anticipated immediate deployment to Panama. On 20 December, as the 96th CA was preparing to deploy, LTC Peters called MAJ Cheek and directed him to get to Panama as soon as possible. Driving through a snowstorm to Fort Bragg, MAJ Cheek caught a military transport and arrived in Panama on Christmas Day .4

Once on the ground, MAJ Cheek found that his soldiers in Company C, who had previously deployed without him, were already assigned to missions throughout Panama. Because the 96th was the only CA unit in Panama, JTF-South tasked it with multiple simultaneous missions. To meet those expectations, LTC Peters had to use every soldier available, and split up his companies and teams as required. With the other 96th company commanders already tasked, MAJ Cheek’s arrival was a godsend to the 96th CA command, which needed a field grade officer to oversee unexpected contingencies. LTC Peters tasked him with pop-up assignments until 27 December. Anticipating that another housing facility would be needed, Lieutenant Colonel Michael P. Peters, Commander, 96th CA Battalion, directed his Company C Commander, MAJ Cheek, to establish a new DC housing facility.5

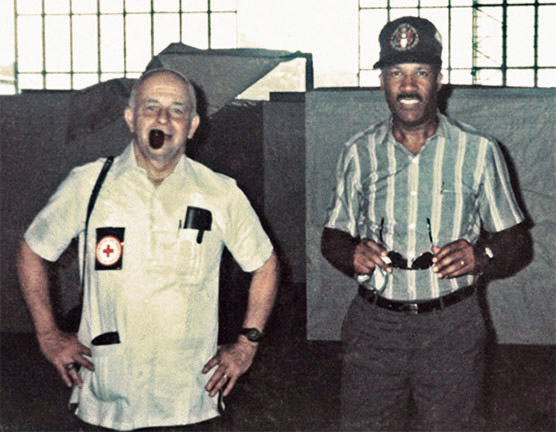

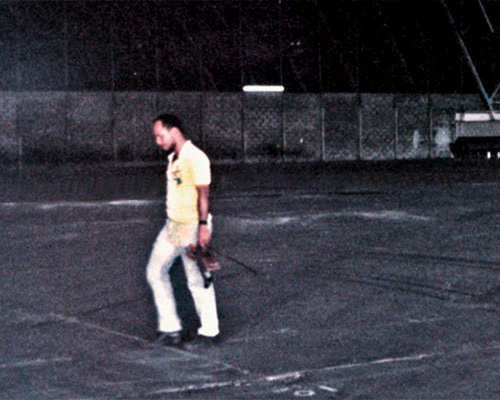

Cheek was put in charge of the project, with no greater elaboration or tasking authority other than “get it done.”6 Because soldiers from the 96th CA were detailed to other missions, he could only expect to receive occasional help and guidance from the battalion staff at nearby Fort Clayton, which was just over a mile away. However, Cheek did have the assistance of supply Staff Sergeant (SSG) Edwin P. Onan, who functioned as an informal liaison with the battalion staff. “Onan,” Cheek noted, “would help scrounge [supplies] and run errands. He had a hundred tasks.”7 In addition, MAJ Cheek visited and talked with the personnel who ran the Balboa DC facility.8 From them, he understood the critical needs that had to be met: sanitation, housing, and medical care. Finally, in early January, when reserve CA personnel deployed to Panama, Cheek received translator assistance from SGT Gabrielle Calderon. However, managing the effort was firmly on Cheek’s shoulders. Despite having no experience in refugee assistance, he became the ‘go-to guy’ who had to solve a multitude of tasks and problems of all sizes to be successful.9