ABSTRACT

Though challenging, the first phase of U.S. Army Psychological Operations (PSYOP) deployments to Saudi Arabia was complete by mid-October 1990. The second phase was complicated by U.S. Army Reserve mobilizations, resulting in the delayed arrival of more PSYOP soldiers until the eve of war in January 1991. Getting a robust PSYOP structure in place was difficult, but in the end, the right soldiers, equipment, and relationships were in place to wage a large-scale PSYOP campaign during Operation DESERT STORM.

TAKEAWAYS

- More than 400 soldiers from active-duty PSYOP units deployed to the theater of operations between August and October 1990; they were joined by roughly another 200 soldiers, many from USAR PSYOP units, in January 1991

- PSYOP units were assigned to the 8th POTF and would follow the same themes set forth in the overarching PSYOP plan; however, due to the unique missionsets (including radio, loudspeaker, print, and EPW operations) and the need to support units across the coalition, the PSYOP campaign itself would be executed in a decentralized manner

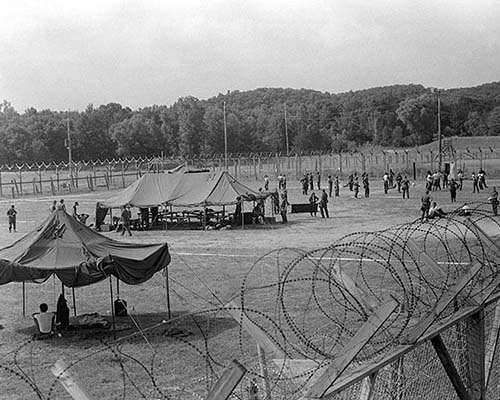

- Between frequent pre-war 8th POB TDYs to USCENTCOM; 13th POB field training with the 800th MP Brigade at Fort A.P. Hill in mid-1990; and the recent combat mission in Panama (1989-1990), many PSYOP leaders and soldiers were well-prepared when it came time for Operations DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM

DOWNLOAD

A previous article, “Rising from the Ashes: PSYOP in Operation DESERT SHIELD,” described the state of U.S. Army Psychological Operations (PSYOP) forces after Vietnam, the background to Operation DESERT SHIELD in the Middle East, and the difficulties of getting a theater PSYOP plan approved in late 1990. As that article explained, no PSYOP units were stationed in the area of operations when Iraq invaded Kuwait on 2 August 1990, although a handful of 8th PSYOP Battalion (POB) soldiers were on Temporary Duty (TDY) with the U.S. Military Training Mission (USMTM) in Saudi Arabia. During that month, they were joined by a few loudspeaker teams accompanying an 82nd Airborne Division rapid deployment force, as well as the theater-level Joint PSYOP Group (JPOG), led by Colonel (COL) Anthony H. Normand, commander of the Fort Bragg, North Carolina-based 4th PSYOP Group (POG). Behind the scenes, plans were underway for a much larger PSYOP presence in anticipation of a wider conflict.

This article details PSYOP deployments during Operation DESERT SHIELD. Between the invasion of Kuwait and the coalition’s initiation of hostilities on 17 January 1991, some 600 soldiers from across the active and reserve component PSYOP force deployed to Saudi Arabia. They were supported by EC-130 VOLANT SOLO aircraft from the 193rd Special Operations Group (SOG). Finally, one PSYOP team deployed to Bahrain to assist the U.S. Information Service (USIS) with Voice of America (VOA) broadcasts, while another deployed to support Joint Task Force (JTF) Proven Force, headquartered at Incirlik, Turkey. Getting the organizational and technical infrastructure in place to wage a landmark PSYOP campaign in support of a massive multinational coalition was no small feat.

Initial Active-Duty PSYOP Deployments

A week after the Iraqi invasion, the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), General (GEN) Carl W. Stiner, ordered the deployment of a PSYOP battalion no later than 24 August 1990, to coincide with conventionaland special operations forces deployments. The U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM)-aligned 8th POB, also based at Fort Bragg, was the clear choice, although the initial timeline proved to be ambitious. The 8th POB commander, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Jeffrey B. Jones, did deploy with the JPOG in late August, but the balance of his battalion did not begin overseas movement until 6 September (with planned completion by 4 October). Within a week of the start of 8th POB’s deployments, 105 soldiers from across the PSYOP force had arrived in Saudi Arabia.1

The 8th POB formed the core of the 8th PSYOP Task Force (POTF), an ad hoc, task-organized element consisting of soldiers and units from across the active-duty and U.S. Army Reserve (USAR) PSYOP force. Assigned to U.S. Army, Central (USARCENT), the 8th POTF headquarters (HQ) occupied space at both the Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC) building (along with the JPOG) and at HQ, USARCENT, in Riyadh. On paper, 8th POTF was the higher headquarters for deployed PSYOP units; in reality, PSYOP forces would be arrayed throughout the entire coalition and were responsible to their supported combat arms units. This would result in a PSYOP effort that was centralized in its themes and intent, but decentralized in execution.

As the 8th POTF commander, LTC Jones had general authority for executing the broad theater PSYOP plan; however, as explained in the previous article, that plan (BURNING HAWK) had been mired in the Pentagon bureaucracy for months awaiting approval. In addition, PSYOP-peculiar equipment arrived slowly and piecemeal, forcing reliance on host nation assets early on. While not an ideal or long-term solution, 8th POTF had access to Saudi TV Channel 2, Saudi Ministry of Defense (MoD) production studios, print facilities, and some Arabic linguists, much of this previously arranged by the PSYOP NCOs at USMTM.2

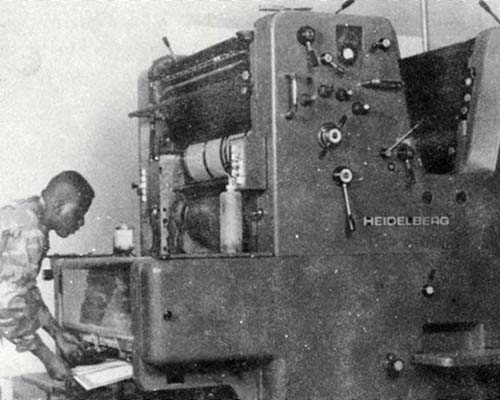

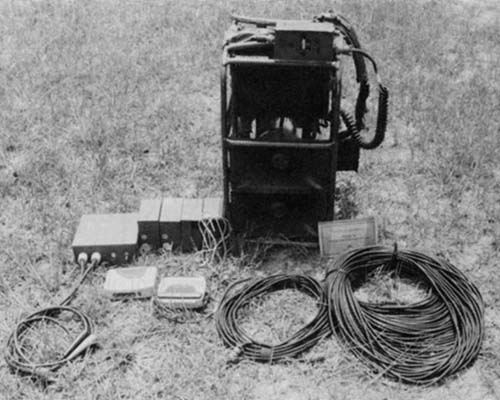

There was a spike in PSYOP deployments throughout September 1990. By mid-month, most 8th POB soldiers slated for deployment had arrived. They were joined in theater by soldiers from the Fort Bragg-based 9th POB, commanded by LTC Thomas D. Washburn. While the 9th POB deployed as a battalion, its soldiers would be broken into small tactical loudspeaker teams and attached to combat units across the coalition. Also deploying was the newly activated PSYOP Dissemination Battalion (PDB) (later reflagged as the 3rd POB). The first PDB soldiers came from the Broadcast Company, commanded by Captain (CPT) Robert Simmons. Behind them were the PDB commander, LTC James P. Kelliher, his staff, and soldiers from the Print and Signal Companies (commanded by CPTs David Milani and Susan Forsythe, respectively). Upon arrival, the PDB commander, staff, and print elements occupied facilities at King Fahd International Airport (KFIA), near Dammam on the east coast of Saudi Arabia.3

With the JPOG and 8th POTF in Riyadh and the 9th POB spread out across the coalition, the PDB was the lone Army PSYOP unit at KFIA. While LTC Kelliher trekked back and forth to Riyadh—around 500 miles round-trip—to discuss plans with COL Normand and LTC Jones, his staff coordinated with local units for food, medical, and dental support. Another order of business was contracting to pave the print facility because “dust was everywhere,” said Kelliher.4 In addition, Signal Company soldiers helped establish a secure communications link between Riyadh, KFIA, and broadcasting outstations at Al Qaisumah and Abu Ali Island, Saudi Arabia, using secured telephone lines provided bythe Saudi-owned Aramco oil company. Kelliher described these collective efforts as “building the airplane in flight.”5