“It thus appears to us here an inescapable conclusion that we must not terminate our efforts in Laos …”1 -U.S. Embassy in Laos, November 1957

DOWNLOAD

In October 1958, Brigadier General (BG) John A. Heintges was nearing the end of his tour as Deputy Commander, U.S. Army Infantry Training Center, at Fort Dix, NJ, and preparing for transfer to Korea when he received a call from the Pentagon. His orders to Korea were cancelled, the person said. “Well, where am I going?” Heintges inquired. Refused an over-the-phone answer due to classification, he was told to report to Rear Admiral (RADM) Edward O’Donnell, Director, Far East Section of International Security, Department of Defense (DoD).2

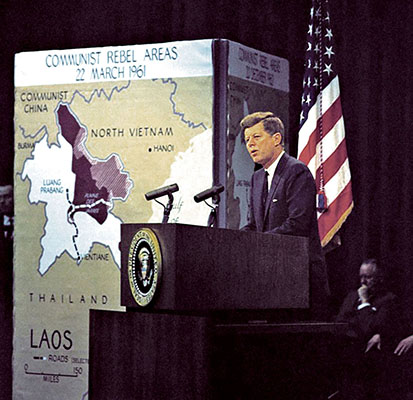

The following day, O’Donnell told the baffled general to go to Laos, a land-locked Southeast Asian (SEA) country formed from the former French colony of Indochina. Bordered by Burma, China, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV, ‘North Vietnam’), the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, ‘South Vietnam’), Cambodia, and Thailand, Laos had a population of around two million, half of whom were ethnic Lao, with the other half comprised of heterogeneous tribal groups.3 In Laos, Heintges would replace BG Rothwell H. Brown as head of the Programs Evaluation Office (PEO), a small, secretive DoD staff agency located in the Laotian capital, Vientiane. The Chief, PEO, represented the military on the U.S. Embassy Country Team.4 Established in 1955, the PEO channeled arms and equipment to the Royal Lao Government to help it combat both internal and external Communist threats, chiefly the Pathet Lao.5

Laos represented a diplomatic challenge for American political leaders. While the U.S. recognized Laotian sovereignty and neutrality, it also followed the Cold War foreign policy of ‘containment,’ or preventing the spread of Communism. Located in the ‘heart’ of SEA, Laos could not be allowed to ‘fall’ to Communism like China did in 1949 or like the Republic of Korea nearly did in 1950. Committed to cost-efficiency, President Dwight D. Eisenhower leaned heavily on diplomacy, nuclear deterrence, and covert operations in foreign policy. While he ruled out open military intervention in Laos, he would also not stand by and ‘do nothing.’

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the PEO, in concert with State Department and U.S. Information Agency (USIA) efforts, deployed non-uniformed advisors to provide clandestine training, logistical support, and funding to the Laotian government.6 Accordingly, Heintges was about to become the ‘civilian’ head of the PEO, answerable to Horace H. Smith, U.S. Ambassador to Laos, and Admiral (ADM) Harry D. Felt, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Command (USPACOM). Heintges’ rank in Laos would simply be ‘Mr.’7

“I found nothing but a rabble … with no discipline and no organization to speak of. Equipment was in terrible shape … it was just awful.”As PEO commander, then-BG John A. Heintges devised the “Shoot and Salute” plan to use U.S. Army Special Forces to train the Laotian military.

Heintges knew little to nothing about his new location; his ‘comfort zone’ was in Europe. He had commanded 3/7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division during World War II; attended Heidelberg University in 1946–1947; served as Chief, Advance Plans and Training Section, U.S. Army, Europe (USAREUR), in 1954–1955; and headed the Operations and Training Branch, Army Section, U.S. Military Assistance Group, in Germany, followed by the Army Section itself, in 1955–1957. He therefore did a 45-day survey of Laos, primarily to evaluate the military, before assuming command of the PEO.

He was disgusted with what he found. “I found nothing but a rabble in half military uniform and half civilian clothes, with no discipline and no organization to speak of. Equipment was in terrible shape and there were no signs that any of our materiel we sent there was being properly maintained. The guns were rusty, the vehicles were in bad shape [with a] shortage of gasoline and so forth; it was just awful.” During the colonial period, the French had filled officer and noncommissioned officer (NCO) positions in the Laotian military. Their mass departure had left a leadership vacuum, which in turn contributed to the further deterioration of the Laotian armed forces. (While some 1,500–2,000 French military advisors remained in Laos after independence, their effort was halfhearted, and “the Laotians paid no attention to them.”)8

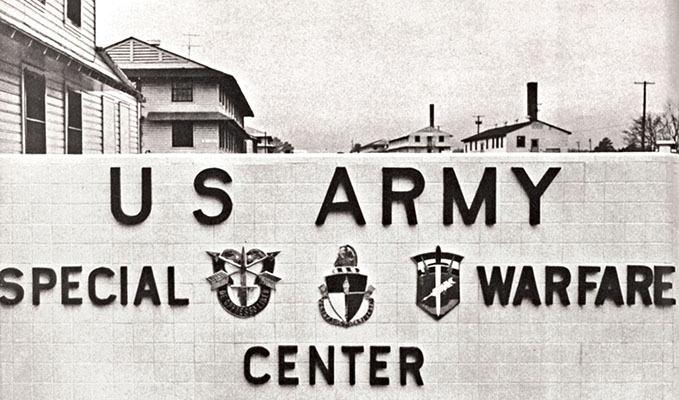

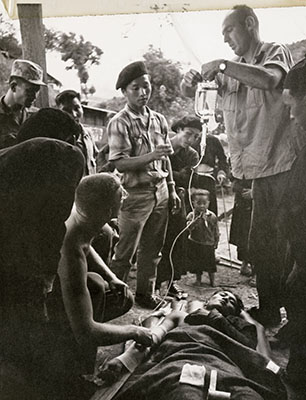

After completing his survey in December 1958, Heintges penned the “Shoot and Salute” plan to instill discipline and basic military proficiency in the Laotian military. This plan formed the basis for seven U.S. Army Special Forces (SF) rotations from July 1959 to October 1962. These SF soldiers came from the 77th, 7th, and 1st SF Groups (SFGs). As part of Project HOTFOOT, non-uniformed SF teams supported the PEO from July 1959 until April 1961, when newly inaugurated President John F. Kennedy replaced the PEO with the Military Assistance Advisory Group, Laos (MAAG Laos). At that point, U.S. soldiers donned uniforms in support of Operation WHITE STAR. The U.S. advisory role in Laos (both CIA and SF) is fairly well documented.9 However, the January 1961 introduction of a twelve-man psychological warfare (psywar) team from the 1st Psywar Battalion (Broadcasting and Leaflet [B&L]), at Fort Bragg, NC, is not. Psywar support to counterinsurgency (COIN) in Laos is addressed in a future article.

This article sets the stage for U.S. Army Special Warfare in Laos, and lays the groundwork for an article on the psywar effort in the next issue of Veritas. First, a short history of Laotian governance, followed by major developments in U.S.-Laos relations, provides the broad context. Second, it details how the U.S. got drawn deeper into Laos by an armed coup launched by ‘neutralist’ Captain (CPT) Kong Le and his American-trained 2nd Parachute Battalion in August 1960. Ensuing U.S. support of anti-Communist Prime Minister Boun Oum and defense minister General (GEN) Phoumi Nosavan put the U.S. at odds with most of the international community, including allies, who recognized Souvanna Phouma as Prime Minister.

Third, this historical account chronicles the path toward creating MAAG Laos in April 1961. President Eisenhower (1953–1961) declined to activate a MAAG, preferring instead to keep the operation ‘under wraps’ and in CIA hands. However, the CPT Kong Le coup (coupled with the unrelated, abortive, CIA-sponsored Bay of Pigs Invasion of Cuba in April 1961) forced the issue, and paved the way for overt U.S. military involvement in Laos. The formal training and advisory mission of MAAG Laos (WHITE STAR) supported President John F. Kennedy’s (1961–1963) flexible response strategy, in which U.S. Army Special Warfare (COIN, psywar, and Unconventional Warfare [UW]) could be employed to combat Communist-backed ‘wars of national liberation.’

Finally, this article introduces U.S. Information Service (USIS) activities in Laos. In order to consolidate all overseas information activities under one agency, President Eisenhower established the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) in 1953 to oversee efforts of its deployed field offices (USIS). (Confusingly, USIA and USIS were two different names for the same organization; ‘USIS’ was simply the overseas version of ‘USIA.’) Aiming to promote Laotian support for the Royal Lao Government and counter Communist propaganda, USIS Laos began activities in 1954. As will be explained, USIS Laos encountered many difficulties, and it benefited greatly from 1st Psywar Battalion (B&L) augmentation starting in 1961. However, before explaining U.S. information and psywar activities, it is first necessary to provide some general background on Laos and the U.S. involvement there.