DOWNLOAD

In January 1961, a twelve-man team from the 1st Psychological Warfare (Psywar) Battalion (Broadcasting and Leaflet [B&L]) deployed to Laos as part of a secretive, small-scale U.S. Army Special Warfare presence to advance U.S. strategic objectives in Southeast Asia (SEA). Assigned to the Programs Evaluation Office (PEO) in the Laotian capital, Vientiane, the psywar team offered multi-media psywar support to U.S. agencies operating in-country, but its primary role was augmenting the U.S. Information Service (USIS). In addition, team members advised the Royal Lao Government and armed forces, which had been fighting the externally-supported Communist Pathet Lao and other insurgents since 1954.

Comprised of mostly junior officers and soldiers, many of them new to the Army or on their first deployment, the psywar team was inserted into a highly ambiguous situation (as explained in the contextual Laos article in the previous issue of Veritas). Afforded little preparation, guidance, or direction from higher headquarters, these soldiers relied heavily on their own education, experiences, and initiative. The team’s selection, pre-mission preparations, and six-month deployment, the focus of this article, are described by three of its members: Second Lieutenant (2LT), Specialist 4 (SP4) Neil E. Lien, and Private First Class (PFC) William J. Dixon.

Born in Nanticoke, PA, on 8 November 1935, 2LT Raymond P. Ambrozak studied Industrial Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, before being drafted into the Infantry in September 1958. His enlisted time was short, as he completed Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning, GA, in October 1959, earning a commission as an Infantry 2LT. Expecting an Infantry assignment, he inexplicably received orders to the 1st Loudspeaker and Leaflet (L&L) Company at Fort Bragg, NC, as a Psywar Officer.1 On 24 June 1960, the 1st L&L was re-designated as the 1st Psywar Company [L&L], a subordinate unit of the 1st Psywar Battalion.2 Adding to his confusion was notification of deployment to an unknown country in SEA a couple of months later. Two other unsuspecting prospective members of the psywar augmentation team were SP4 Neil E. Lien and PFC William J. Dixon.

“There’s only one place for you to go:

psywar.”

Born, raised, and educated in western Chicago, Neil E. Lien attended Lawrence College in Appleton, WI, where he double majored in English/Creative Writing and Speech Arts. The latter discipline encompassed such fields as theater, oral interpretation, and radio broadcasting. He also minored in psychology and worked at the college radio station. Graduating in June 1958, Lien waited “for the shoe to drop (for my draft notice to come).” In anticipation, he bought the Draftee’s Guide to Military Life and Law. Receiving his draft notice in late summer 1959, then-Private (PVT) Lien felt prepared. While in basic training at Fort Ord, CA, he had his Classification and Assignments (C&A) interview with a career counselor to determine his Military Occupational Specialty (MOS). Looking at his fields of study and radio broadcasting experience at Lawrence, the NCO said, “There’s only one place for you to go: psywar.” He reported to Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 1st Psywar Battalion (B&L), on Smoke Bomb Hill, Fort Bragg, in late 1959, as a radio broadcaster.3

William J. Dixon was born, raised, and educated in Dixon, IL. He attended the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, IN, graduating in June 1959 with a B.A. in Fine Arts. His father, a retired colonel who had served in both World Wars, felt strongly about his five sons joining the military. Accordingly, in 1959, Bill enlisted for two years as an Army Illustrator. He attended basic training at Fort Riley, KS, before reporting to the HHC (S-3), 1st Psywar Battalion (B&L), around Thanksgiving, as one of seven illustrators in the battalion.

After six months learning from more experienced illustrators and performing ‘extra duties as assigned,’ Dixon got wind of a real-world ‘opportunity.’ “One day, I got an urgent message to get back to my company,” recalled Dixon. Informed by his leadership that he may be deploying on a secret mission, he was not sure why he among the illustrators was selected. He suspected that since he was an ‘excess’ soldier above and beyond the battalion’s Table of Organization and Equipment (T/O&E), the unit had wanted to send him so as not to lose assigned personnel.4

Lien had another theory for their selection. “First, we all had good reputations. I was Soldier of the Month twice, I never caused any problems, and I was really affable with the other guys. The second consideration was skills—what skills were needed to build this team, and who had them? For example, mine was radio broadcasting.” Finally, each enlisted member had to have enough time left in service for the deployment. Lien had just enough, with two months to spare. “On those three criteria, that’s how I qualified.”5

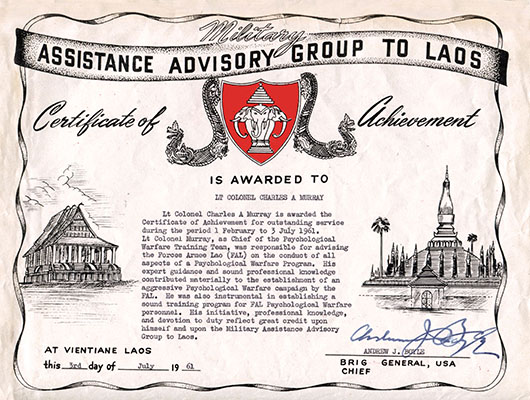

Lien, Dixon, and sixteen other prospective candidates—including a civilian and a major—met in an empty barracks for a more detailed rundown. “They didn’t tell us where the mission was, but said it would be for roughly six months,” said Dixon. Interested people would need to get a security clearance, a time-consuming process; therefore, they needed to volunteer ‘on the spot.’ “Everyone raised their hands. However, within a month or so, there was a shakeout and it narrowed down to twelve.” The major had to leave for another assignment, and was replaced as Officer-in-Charge (OIC) by Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Charles A. Murray.6 Eventually ‘filled in’ on the particulars and sworn to secrecy, the team began ad hoc pre-deployment training.

Slated to arrive in Laos by September 1960, the team had about six weeks to prepare for deployment. The 1st Psywar Battalion (B&L) provided no training regimen, so they developed their own. According to 2LT Ambrozak, they built an “area study” to familiarize themselves with the people, culture, economy, and political situation in Laos. “We parsed out each one of these areas to different members of the team.” Once an individual completed his ‘class,’ he presented it to the group. In addition, the team received a crash course in the Lao language from a 7th Special Forces (SF) Group NCO (non-commissioned officer) who had spent a year in-country and had picked up 200–300 words. Ambrozak pointed out that while the language training was minimal, it actually did help “promote a quick relationship with the local Lao people” during the deployment.7

In August 1960, the team had nearly completed its pre-deployment training when its overseas movement was delayed due to the chaos in Laos following Captain (CPT) Kong Le’s insurrection. The group took advantage of the time by improving their area study and continuing ad hoc language training in French and Lao. Having lost their SF language instructor, the team elected one of their own who had earlier gotten the best scores in the Lao language: 2LT Ambrozak. “I became the language instructor for a country I didn’t even know existed six weeks prior to that,” he remembered.8 For the rest of 1960, the team continued learning more about its host country.