FULL SERIES:

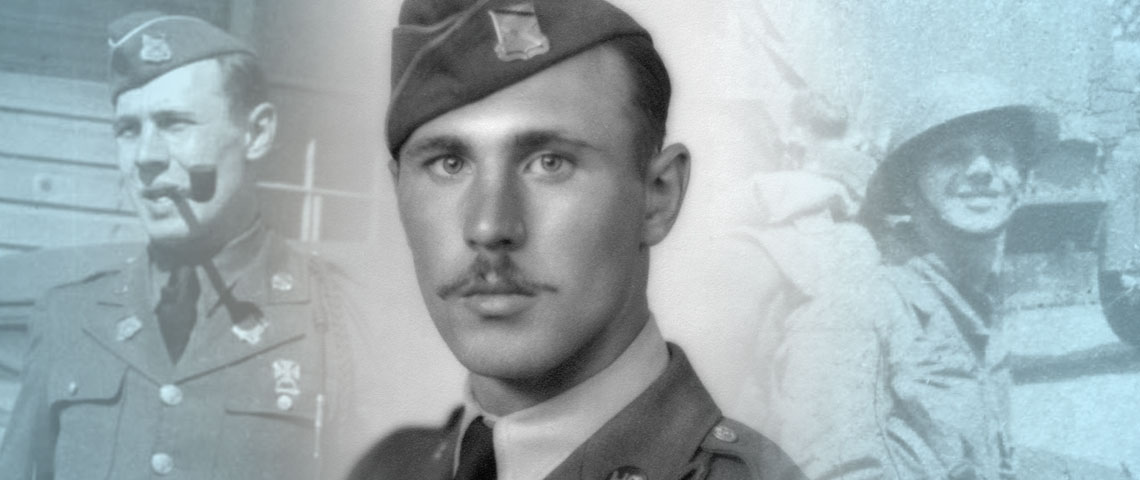

Major Bruckner

Part I: SOE France, OSS Burma and China, 10th SFG, SF Instructor, 77th SFG, Laos, and Vietnam

Part II: Pre-WWII–OSS Training 1943

SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

The short biography and photo essay in Part I: SOE France, OSS Burma and China, 10th SFG, SF Instructor, 77th SFG, Laos, and Vietnam introduced Major Herbert R. Brucker, one of the pioneers of Special Forces. In twenty years, Brucker acquired a wealth of special operations experience that merits sharing with the Force. Therefore, Part II covers his developmental period of military service before World War II as a CW (Morse Code) radio operator in an infantry regiment through his OSS (Office of Strategic Services) special operations agent training before being detailed to the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) in England. This article will show why and how Brucker was selected to train as an OSS operative, cover facets of the SO assessment and training course, and conclude with his overseas shipment to England.

The Part One photo essay introduced Herbert R. Brucker as a former radio operator of a three-man SOE team that conducted clandestine operations in France before D-Day. British special operations (SO) and special intelligence teams, unlike OSS Jedburgh and Operational Groups, had been operating behind German lines throughout Europe since late 1940. Technical Sergeant Fourth Class (T/4) Brucker was detailed from the OSS to the SOE in England because he had been raised in France and Germany, was naturally fluent in French and German, and was culturally attuned. To fully appreciate what this soldier accomplished in the Army and did for special operations, the reader must keep in mind that Brucker joined the service in 1940—at the time understanding, speaking, reading, and writing very little English. He grew up in France and Germany, living there for seventeen years. Though a graduate of the equivalent to the American high school in France, Brucker is self-educated in English and retired from the Army as a major after twenty years of service.

His French father, who immigrated to America in 1911, joined the U.S. Army as an infantryman and fought Moslems in the Philippines during the Moro War. Medically retired after losing an arm at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Ernest Brucker married the rebellious daughter of a middle-class immigrant German family in New Jersey. Six months after the birth of Herbert on 10 October 1921, the couple relocated to Merlebach, France. Ernest became an interpreter for the U.S. Army in the Rhineland and served the French military intelligence. When Herb’s mother, Gertrude Promer Brucker, was pregnant with another child, she returned to the United States. At that point in 1924, the responsibility, care, and education of Brucker became a constant game of “musical chairs.”1

He was bounced between relatives living in villages and farms in the Alsace-Lorraine—the often-contested French province bordering southern Germany—and paid caretakers in France and Germany. Then, Brucker joined his father in Metz for a short time before ending up in a Parisian boarding school with his younger brother. After that experience, Brucker returned to Merlebach to attend school and serve as an apprentice tool and die maker for a coal mining company. Finally, he took a job as a temporary agricultural worker—a “cowboy” (barefoot cow herder)—in central France, after a Parisian baker refused to hire him as a helper. Being Alsatian, his efforts to join the French Army were politely rebuffed despite war clouds building over Europe. The recruiters suggested the Foreign Legion. To make matters more difficult, it was the Great Depression.2

Thus, over the years his unique Alemanische (a German dialect spoken in the Alsace-Lorraine region) was transformed into high Deutsche and the French he had learned in Valence while “boarded” with a Muslim-Algerian family was transformed into Parisienne while in a boarding school north of Paris. Meanwhile, after being imprisoned in Spandau for spying, Brucker’s father left for the United States with a new wife. It was an American birth certificate that finally enabled his father to bring Brucker back to the United States in November 1938.3

Having lived in France and Germany for seventeen years, Brucker was really a Frenchman with American citizenship. He struggled to learn English on the streets of Newark, New Jersey, by reading comic books, going to movies, and working in restaurants. His father, a pastry chef and restaurant steward, had numerous contacts. But, understanding English proved to be important in food service. “Once I tried to make mayonnaise with eggs and maple syrup instead of vegetable oil,” said Brucker, “because the contents of the can seemed right. I simply could not read the label.” After almost two years “bouncing from job to job,” Brucker was lonely and quite disenchanted with America. That is what caused him to join the Army.4

When Brucker was rejected by New York’s “Fighting 69th” Division (National Guard) because of his size, his father had him eating bananas every meal to gain weight for the Regular Army. Because Ernest was an amputee American war veteran, the recruiter let him “help” his son during the written examination. In October 1940, Herbert R. Brucker enlisted and was sent to Fort Hamilton, New York. “In some ways it was a relief. The U.S. Army became my home. I didn’t need parents any longer. The Army was now my family,” said Brucker. “The Army gave me clothes. I was served meals in a dining hall. I shared a room. I slept on a bed with sheets. Life was good.”5 Still, learning a new language and adapting to the culture required considerable time.

A mastery of English, however, was not essential to be a good telegrapher; Morse Code (CW) was an international language. And Private Herbert R. Brucker, Headquarters Company, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division, became quite proficient because he loved being a soldier and was intent on doing well. He diligently practiced Morse Code every day at Fort Hamilton to steadily increase his words-per-minute speed. Basic soldiering skills (referred to now as basic and advanced individual training) were taught by unit corporals and sergeants in pre-WWII days.6

By the time the 1st Division united its three infantry regiments (under the new German triangular organization) at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, to prepare for the Regular Army training exercises at Fort Benning, Georgia, scheduled for the spring of 1940, Private Brucker, wireless radio operator, could send and receive almost twenty words of CW a minute. And because he spoke two foreign languages, the young soldier was assigned to the reconnaissance element.7 A year later, the newly redesignated 1st “Infantry” Division would truck-convoy from Fort Devens to the Carolina Maneuvers. However, few truck drivers existed in the Army of 1941.