DOWNLOAD

Camp Mackall, North Carolina, now a training area for Army Special Operations, was the headquarters of the U.S. Army Airborne Command during World War II. It was named for Private John Thomas Mackall, 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion, one of America’s first paratroopers killed in action. Mackall was wounded by a strafing Vichy France fighter aircraft on 8 November 1942, and died of his wounds four days later. It was at Camp Mackall that the 11th, 13th, and 17th Airborne Divisions were activated and trained. It was also where the U.S. Army Airborne Command evaluated airborne tactics and techniques and tested equipment. One dicey test was to jump paratroopers from towed gliders. After six tests, the method was deemed impractical and too dangerous for both jumpers and the jump platforms. The activity is a little-known aspect of Camp Mackall’s history.

The unit chosen for the test was the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion (PIB). The 551st, known as the GOYAs based on commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Wood C. Joerg’s favorite expression, “Get Off Your Ass!” was a unique unit.1 It became one of only two independent parachute battalions that saw action in WWII, the 509th PIB was the other one. The GOYAs were formed to guard the Canal Zone against possible Axis attack. When an infantry battalion was sent to Panama, the jungle-trained GOYAs were reassigned to Camp Mackall on 8 September 1943. There, they remained until 11 April 1944, when they left for Italy. By the time the GOYAs arrived at Camp Mackall, they were bored and itching for excitement. They welcomed the opportunity to test new parachuting techniques.

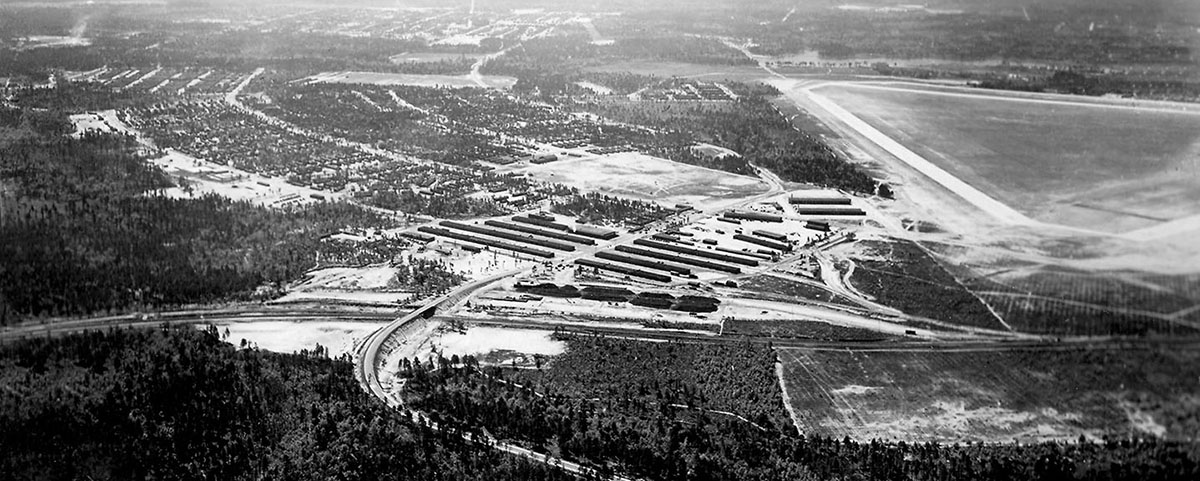

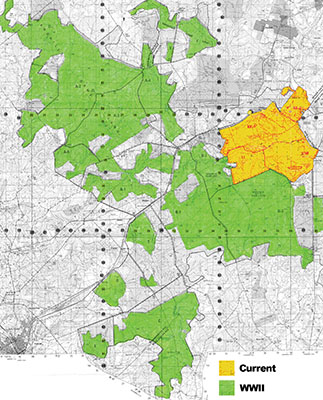

Camp Mackall was an ideal location for the U.S. Army Airborne Command to validate airborne tactics and techniques. In contrast to its current size of 7,916 acres, the Camp Mackall area encompassed more than 70,000 acres in WWII, counting the adjacent civilian-owned land where the Army had maneuver rights. Much of the area collectively known today as the North Carolina–owned Sandhills Wildlife Areas was part of Camp Mackall during the war. This large expanse provided a large maneuver area for the airborne-forces-in-training that surrounded what became a small “city” in the Carolina Sandhills. Mackall was also close to the Army airfield at Laurinburg-Maxton and in an area that was free of commercial air traffic.

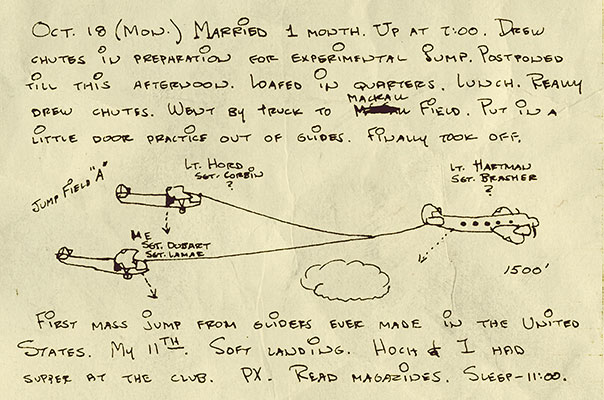

In October 1943, the Airborne Command decided to evaluate the suitability of CG-4A Waco gliders as paratrooper delivery platforms. The logic was that with paratroopers simultaneously jumping from two CG-4As and their C-47 Skytrain tow aircraft, then the number of combat paratroopers jumped could be doubled. It was anticipated that the paratroopers would land in a more compact group, thereby avoiding a scattered drop.2 The fact that the towing C-47s would be flying so slow, however, meant that the entire flight would be “sitting ducks” for anti-aircraft fire. Technician Fifth Grade Daniel Morgan recalled that a few weeks after the 551st got to Camp Mackall, LTC Joerg volunteered for jump testing. “Notices appeared on the company bulletin board calling for volunteers … signature sheets immediately filled to overflowing, for we badly needed something to do.”3 Lieutenant Richard Mascuch does not remember volunteering. He recalls being told that he would be jumping from gliders later that day.4

In all, paratroopers of the 551st made six test jumps from the CG-4A Waco glider from late October 1943 to November 1943; five at Camp Mackall and one at Alachua Army Airfield in Florida.5 The first test jump took place at Camp Mackall on 18 October. It was followed the next day by another with some eighty paratroopers involved. On the 20th, a few paratroopers flew from Camp Mackall to Florida for their first demonstration jump.6 Back at Camp Mackall, on 21 October, a demonstration jump was made for British and American “top brass,” which included a British Air Marshall, Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair, Commanding General Army Ground Forces, and Major General E.G. Chapman, Commanding General of the Airborne Command.7 Staff Sergeant Jack Carr recalled that the men jumped on a drop zone that was concealed by a grove of trees, where fresh troops lay hidden. After the paratroopers had landed, the other group left their hiding places and rushed out into the clearing to show the assembled “brass” that the experiment was an unqualified success!8